Emma is a historian specializing in Northern European medieval and early modern history. Her research often explores the sociopolitical structures of Scandinavian societies, the role of trade and commerce in medieval city development, and the interactions between different cultural and religious groups across the Baltic Sea. She enjoys tracing how historical events shaped the lives of everyday people and finding connections between past and present societal trends.

Julia is a geologist with a focus on glacial and coastal geomorphology. Her fieldwork has taken her to the Arctic Circle, where she studies how glacial movements have shaped the Nordic landscapes over millennia. Her research interests extend to the impact of climate change on these landscapes and the resulting ecological shifts. Julia is intrigued by the relationship between geology and geography, especially how physical landscapes influence human settlement patterns and cultural development.

After attending a conference at the University of Turku, Emma and Julia stroll through the historic university campus.

Emma: The architecture here feels so Scandinavian yet so distinct. It’s intriguing to think how Turku was once the heart of intellectual life in Finland, especially under Swedish rule.

Julia: Absolutely. And for geologists, this place is quite a gem. Turku’s location on the southwestern coast gives it access to fascinating coastal and glacial formations. The bedrock here has endured so many cycles of glaciation.

Emma: I imagine it gives you a unique perspective. This area has seen so many cultural and environmental transitions—from Swedish influence to Russian, and then Finnish independence. That’s a layered history in both land and people.

Julia: Exactly. Each shift in power and culture leaves its mark not only in people’s lives but in how they use the land. Even the coastal erosion here can tell a story about human activity and natural forces.

Emma: It’s fascinating how interconnected history and geology can be. I think that’s why I love traveling with you, Julia. You remind me that history isn’t just in the records but in the landscape itself.

Note: The University of Turku, located in Turku, one of Finland’s oldest cities, boasts a rich academic tradition. Founded in 1920, the university is renowned for its research in the humanities and natural sciences, with extensive resources dedicated to the study of history and ecology in the Nordic and Baltic regions.

Emma 是一位歷史學家,專門研究北歐中世紀及近代早期的歷史。她的研究經常涉及斯堪的納維亞社會的社會政治結構,中世紀城市發展中的貿易和商業角色,以及波羅的海地區不同文化和宗教群體之間的互動。Emma 尤其喜歡探索歷史事件如何影響普通人的生活,並發掘過去和現在社會趨勢之間的聯繫。

Julia 是一位地質學家,專注於冰川和海岸地形學。她的野外研究常帶她前往北極圈,研究冰川運動如何在數千年間塑造北歐的地形。她的研究興趣還包括氣候變遷對這些地貌的影響,以及因此帶來的生態轉變。Julia 對地質與地理之間的關係特別感興趣,尤其是自然地貌如何影響人類的定居模式與文化發展。

在圖爾庫大學參加研討會後,Emma 和 Julia 在校園內散步。

Emma:這裡的建築有著濃厚的斯堪的納維亞風格,但又很有自己的特色。很難想像,圖爾庫在瑞典統治時期曾是芬蘭的學術中心。

Julia:沒錯。對地質學家來說,這裡是個寶地。圖爾庫位於西南海岸,擁有迷人的海岸和冰川地形。這裡的基岩經歷了多次冰川週期,特別具有研究價值。

Emma:我能理解這會帶給你不一樣的視角。這片區域經歷過瑞典、俄羅斯的統治,再到芬蘭的獨立,文化和環境的變遷非常多層次,既影響土地也影響人們。

Julia:是的,每次政權和文化的更替都不僅留下了人文的痕跡,也影響了土地的利用方式。甚至連這裡的海岸侵蝕都能講述人類活動與自然力量的故事。

Emma:歷史與地質的緊密聯繫實在令人著迷。我想,這也是為什麼我喜歡和你一起旅行。你讓我記得,歷史不僅存在於書面記錄中,也存在於這片土地上。

註:芬蘭的圖爾庫大學(University of Turku)。圖爾庫是芬蘭最古老的城市之一,且擁有深厚的學術傳統。圖爾庫大學創立於1920年,這所大學以人文和自然科學研究著稱,並在北歐和波羅的海地區的歷史和生態研究方面有豐富的資源。

The Lifeline of Turku: The Aura River’s Influence

Emma and Julia leave the university and wander through Turku’s Old Town, strolling along the Aura River.

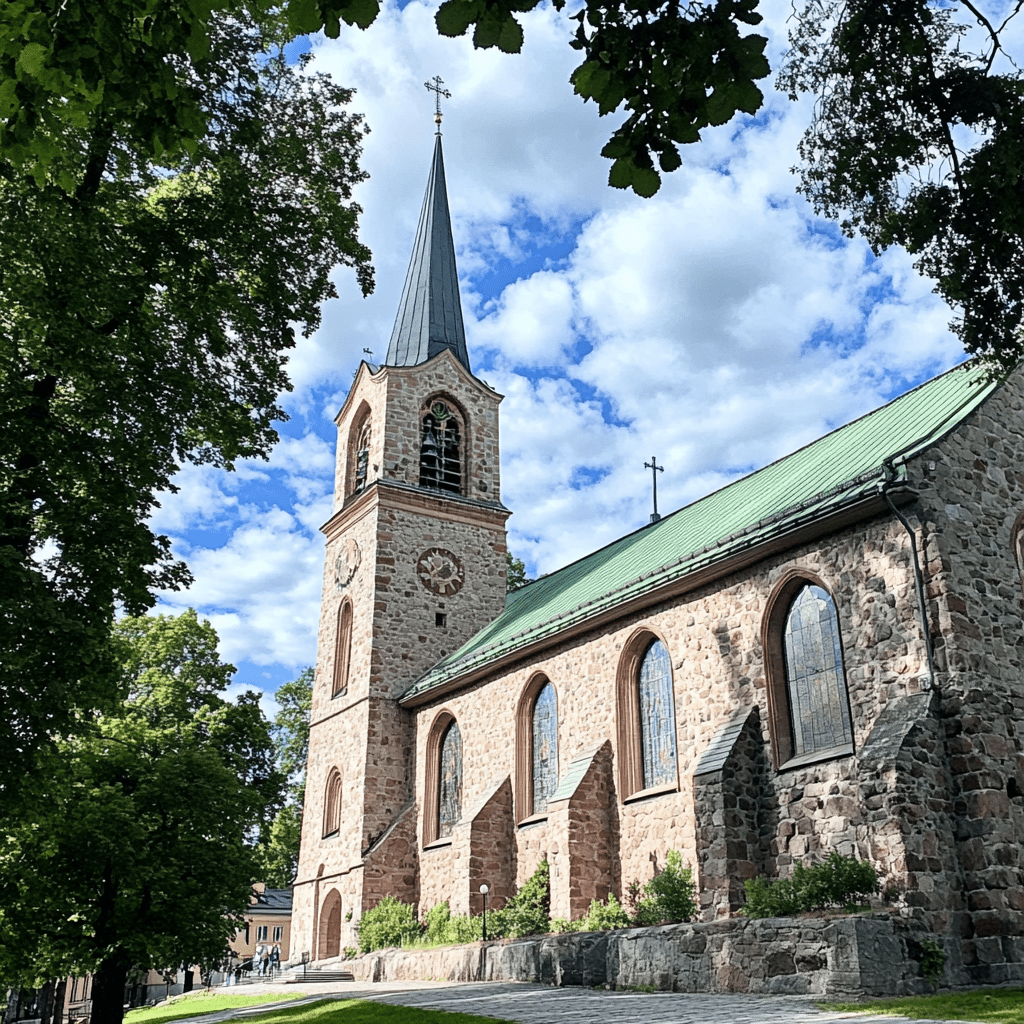

Emma: Walking through these old cobbled streets, it’s easy to imagine how lively this place must have been centuries ago. Turku Cathedral up ahead was once the center of Finland’s religious and cultural life.

Julia: Yes, and the Aura River played a huge role in Turku’s development as a trade hub. This river not only shaped the landscape but also determined where people settled, worked, and even built places of worship.

Emma: It’s fascinating how a single river can influence an entire city’s identity. I read that during the medieval period, much of Finland’s trade with Europe was conducted right here. The stones we’re stepping on might have seen merchants from as far as the Hanseatic League.

Julia: And yet, the river was also a threat. Floods over the centuries have altered the banks, forcing people to adapt constantly. Geology often works that way—a force of creation and destruction, shaping human decisions over time.

Emma: I suppose that’s what makes Turku so unique. It’s a place of resilience, shaped by both human ambition and nature’s unpredictability. Walking here, it feels as though history and geology have a kind of conversation themselves.

Julia: Exactly. We read history in buildings and records, but the landscape itself is like a silent chronicle, telling us what we can’t see on paper. I think that’s what keeps drawing me back to places like this.

奧拉河的影響

Emma 和 Julia 離開大學,漫步在圖爾庫的老城區,沿著奧拉河散步。

Emma:走在這些石板路上,很容易讓人想像,幾個世紀前這裡該是多麼繁華。前方的圖爾庫大教堂,曾是芬蘭宗教和文化生活的中心。

Julia:是的,而且奧拉河在圖爾庫的發展中扮演了重要角色。這條河不僅塑造了地形,也決定了人們的定居點、工作場所,甚至是崇拜場所的位置。

Emma:真讓人著迷,一條河流就能影響整個城市的身份。我讀過,中世紀時期,芬蘭與歐洲的大部分貿易都是在這裡進行的。我們現在踩的石板,或許見證過來自漢薩同盟的商人。

Julia:然而,這條河同時也是一種威脅。幾個世紀以來的洪水改變了河岸,人們不得不不斷適應。地質常常如此,既是創造的力量,也是破壞的力量,影響著人類的決策。

Emma:這大概就是圖爾庫的獨特之處吧。這是一個韌性的象徵,由人類的雄心和自然的不可預測性共同塑造。在這裡漫步,感覺像是歷史和地質本身也在對話。

Julia:沒錯。我們在建築和文獻中讀到歷史,而地貌則像是一部無聲的編年史,告訴我們那些紙上看不到的故事。或許,這就是為什麼我總被這樣的地方吸引。

The Finnish Language: A Unique Bridge Between East and West

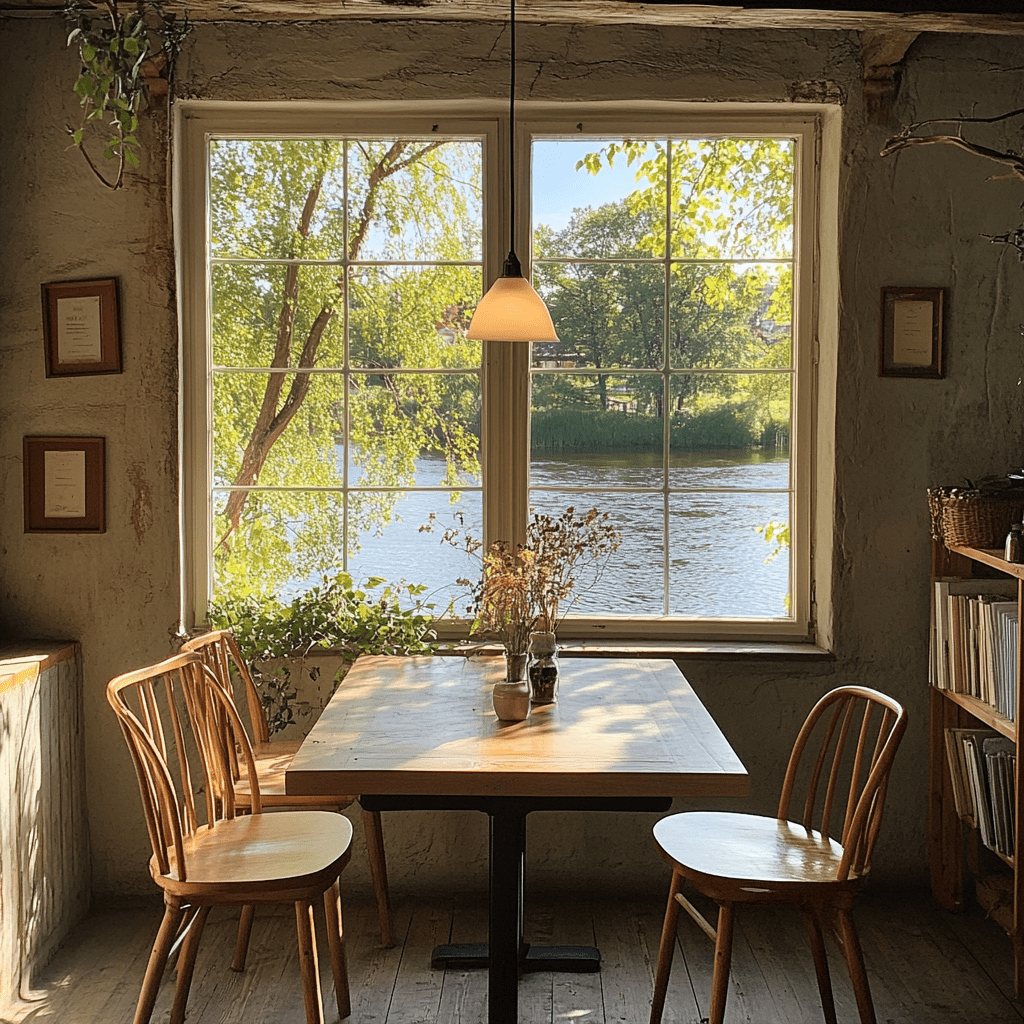

Emma and Julia sit down at a cozy café near the Aura River in Turku, surrounded by the warm, rustic decor typical of Finnish coffeehouses.

Emma: Finnish cafés have such a unique ambiance. It’s calm and simple, yet somehow feels deeply rooted in tradition. Makes me think of how the culture here is distinct yet shares threads with neighboring countries.

Julia: True. Finland is such a fascinating blend. Linguistically, Finnish is entirely different from Swedish or Norwegian. It’s from the Finno-Ugric language family, which links it closer to Estonian and Hungarian than to the Scandinavian languages.

Emma: That always fascinates me—how a language can develop so independently even within close proximity to its neighbors. Yet, culturally, Finland still has a lot of Swedish influence. I mean, look at Turku itself, with so much of its architecture and early history shaped by Swedish rule.

Julia: And Swedish is still an official language here. It’s remarkable how a country can hold onto that dual identity. Even geographically, you see how Finland’s landscape feels like a bridge between the rugged, mountainous terrain of Norway and the flat expanses of Russia.

Emma: It’s a complex identity, isn’t it? Finland seems to sit at a crossroads, both linguistically and culturally. I read that many Finnish traditions, like sauna culture, are shared with other Baltic and Scandinavian countries, but the way Finns have integrated them feels uniquely Finnish.

Julia: Absolutely. And I think the quiet, reserved nature of Finnish people also sets them apart. There’s an understated warmth here that isn’t as immediately obvious as in some other cultures, but it’s deeply sincere.

Emma: It’s subtle, just like the design of this café—nothing overly ornate, just a warm space to gather. Maybe that’s what defines Finnish culture in many ways—subtle, but meaningful.

芬蘭的語言:連結東西方的獨特橋樑

Emma 和 Julia 坐在圖爾庫河畔的一家溫馨小咖啡館中,周圍是典型的芬蘭咖啡館溫暖質樸的裝飾風格。

Emma:芬蘭的咖啡館有種獨特的氛圍。安靜而簡單,卻又帶有深厚的傳統感。讓我想到,這裡的文化雖然獨特,但和鄰國也有許多相似之處。

Julia:是啊。芬蘭是一個有趣的混合體。在語言上,芬蘭語和瑞典語或挪威語完全不同。它屬於芬烏語系,反而和愛沙尼亞語和匈牙利語更接近,而不是斯堪的納維亞語系。

Emma:這讓我很著迷,語言能在這麼近的地理環境中發展得如此獨立。然而,在文化上,芬蘭仍然受到瑞典的很大影響。比如圖爾庫,這裡的建築和早期歷史都深受瑞典統治的影響。

Julia:而且,瑞典語至今還是官方語言之一。這種雙重身份真的很特別。甚至在地理上,芬蘭的地貌也像是挪威崎嶇山脈和俄羅斯平原之間的橋樑。

Emma:這種身份真是複雜啊。芬蘭似乎在語言和文化上都是個交匯點。我還讀到,很多芬蘭的傳統,比如桑拿文化,和波羅的海及斯堪的納維亞國家共有,但芬蘭人以自己的方式融入,使之成為獨具特色的芬蘭文化。

Julia:完全同意。而且我覺得芬蘭人內斂、沉穩的性格也讓他們與眾不同。這裡的溫暖並不是那麼顯而易見,但卻是真誠而深厚的。

Emma:是種低調的溫暖,就像這家咖啡館的設計——沒有過於華麗的裝飾,卻是一個讓人聚會的溫馨空間。或許這正是芬蘭文化的特點——細膩而有深意。

Finnish Sauna Culture: A Tradition of Relaxation and Reflection

Emma and Julia are enjoying a cup of coffee in a cozy Finnish café, and the conversation turns to the topic of saunas.

Emma: I find it fascinating how ingrained the sauna is in Finnish culture. It’s almost like a ritual here, isn’t it?

Julia: Absolutely. Saunas are practically a national treasure in Finland. They’re not just about relaxation; they’re deeply connected to Finnish identity and tradition. You’ll find saunas in nearly every Finnish home, apartment building, and even workplaces.

Emma: Do you think it’s related to the climate here? The long, cold winters must have made hot spaces like saunas very appealing.

Julia: That’s definitely part of it. Historically, saunas served multiple purposes—people would bathe, give birth, and even treat illnesses in the sauna because it was the warmest and cleanest place in the house. In a way, it became a place of both physical and spiritual cleansing.

Emma: I read that the Finns don’t actually have many natural hot springs, unlike places like Iceland or Japan. So saunas are more of an adaptation to the cold rather than a direct result of geothermal activity.

Julia: Exactly. The Finns didn’t have hot springs, but they found another way to bring heat into their lives. Early saunas were actually more like smoke saunas, where they’d heat stones until they were very hot, then pour water over them to create steam. It’s a very ancient tradition, probably dating back thousands of years.

Emma: It’s amazing to think how something so practical evolved into such an essential part of the culture. For Finns, it seems like the sauna isn’t just a place to warm up, but a place to connect, reflect, and even find peace.

Julia: That’s very true. In fact, it’s common for Finns to take saunas together, even with strangers, yet it’s a quiet, almost meditative experience. It’s as though the sauna itself demands a kind of respect and introspection.

Emma: I guess that’s why it’s remained so popular. It’s not just a habit; it’s an experience that connects people to their roots and to each other.

芬蘭的桑拿文化

Emma 和 Julia 坐在芬蘭的一家溫馨小咖啡館裡,談話間聊到了桑拿文化。

Emma:我覺得芬蘭的桑拿文化特別有意思。這幾乎成了一種儀式,不是嗎?

Julia:的確。桑拿對芬蘭人來說幾乎是一種國寶。不僅僅是放鬆,它還深深地與芬蘭人的身份和傳統相連。幾乎每個芬蘭家庭、住宅樓,甚至辦公場所都有桑拿。

Emma:你覺得這和這裡的氣候有關嗎?漫長而寒冷的冬天讓人們對這種熱空間特別渴望。

Julia:這肯定是一個原因。歷史上,桑拿不僅僅是用來洗澡的,它還是一個生產的場所,比如接生,甚至是治療疾病的地方,因為桑拿是屋內最溫暖和最乾淨的空間。在某種程度上,它成了一個身體和精神雙重淨化的地方。

Emma:我聽說,和冰島或日本不同,芬蘭其實沒有什麼天然溫泉。所以桑拿其實是適應寒冷氣候的產物,而不是來自地熱活動。

Julia:沒錯。芬蘭人沒有溫泉,但他們找到了一種方法來將熱帶入生活。早期的桑拿其實是煙熏桑拿,人們會將石頭加熱,然後澆水產生蒸汽。這是一個非常古老的傳統,可能可以追溯到幾千年前。

Emma:真是讓人驚嘆,一種這麼實用的東西能演變成文化的核心之一。對於芬蘭人來說,桑拿似乎不僅僅是取暖的地方,更是一個聯繫、反思甚至尋找內心平靜的場所。

Julia:的確如此。其實,芬蘭人經常會和朋友甚至陌生人一起蒸桑拿,但那是一種安靜、幾乎是冥想的體驗。好像桑拿本身就帶著一種敬意和內省。

Emma:或許這就是為什麼桑拿一直這麼受歡迎。它不僅僅是一種習慣,而是一種將人們與根源和彼此聯繫起來的體驗。

Still at the cozy café, Emma and Julia’s conversation about sauna culture deepens.

Emma: It just occurred to me—keeping a sauna heated must require a lot of energy, especially in these cold winters. Did they rely on wood for all that heat?

Julia: Yes, traditionally, they used wood-burning stoves. In fact, wood is still a preferred heat source for saunas because it gives a specific kind of warmth and humidity. They would use slow-burning logs to maintain the temperature, which required a lot of skill in managing the fire.

Emma: So it’s a bit of an art as well, knowing how to keep the fire just right. But wood must have been a scarce resource during harsh winters, especially up north.

Julia: That’s true. Finland is fortunate to have large forests, so wood has traditionally been more accessible here. In many ways, the abundance of forests allowed the sauna culture to thrive. However, as energy needs grew, they adapted. Now, many saunas use electric heaters, which are easier to control and don’t require as much wood.

Emma: That makes sense. It’s interesting to think about how this compares to other cultures. In Russia, they have a similar tradition called the banya, which also involves heating up stones and creating steam. But it’s slightly different, isn’t it?

Julia: Yes, the Russian banya is quite similar, but they typically use more intense heat and often follow it with a plunge into ice-cold water. It’s a bit more vigorous. And in Japan, while they don’t have a sauna culture exactly, they do have onsen—hot spring baths—which rely on natural geothermal heat.

Emma: I suppose the main difference is that Japan’s onsen culture is heavily influenced by the volcanic activity that creates natural hot springs. In contrast, Finland and Russia had to create their own heat sources. It’s impressive that the Finns were able to make sauna a central part of their culture without natural geothermal resources.

Julia: Exactly. That’s what makes it unique. While places like Iceland, Japan, or even New Zealand have natural hot springs, Finns had to innovate to recreate that experience. In a way, it’s a testament to their resilience and creativity in making their own comfort in a harsh climate.

Emma: And over time, they’ve refined it into something beyond just warmth—sauna has become a place for socializing, relaxation, and even meditation. It’s fascinating how a practical solution to cold weather turned into a cultural pillar.

Julia: It’s a perfect example of cultural adaptation. Even today, modern saunas retain that deep-rooted connection to Finnish identity, even if the heat source has shifted from wood to electricity.

桑拿文化中的熱源

在溫馨的咖啡館裡,Emma 和 Julia 的對話更加深入,討論桑拿文化中的熱源問題。

Emma:我剛剛想到,要維持桑拿的高溫在這麼冷的天氣裡應該需要大量的能量。他們主要是依靠木材來加熱嗎?

Julia:是的,傳統上他們使用木材爐來加熱。其實,至今木材仍然是許多芬蘭人最喜歡的熱源,因為它能提供特別的溫暖和濕度。他們會選擇耐燒的木材來維持溫度,這需要一定的技巧來控制火勢。

Emma:所以這也是一門技藝,知道如何保持火候剛好。但在嚴寒的冬季,尤其是北方,木材應該是稀缺資源吧?

Julia:確實如此。不過,芬蘭的森林資源非常豐富,這讓他們有了充足的木材供應,桑拿文化才能繁榮起來。然而,隨著能量需求的增加,芬蘭人也開始適應現代技術。現在,許多桑拿使用電熱器,控制更方便,也不需要那麼多木材。

Emma:這樣就說得通了。比較起來,其他文化中也有類似的熱源文化。比如在俄羅斯,他們有類似的傳統,叫做 banya,也是加熱石頭並產生蒸汽,不過略有不同,是吧?

Julia:對,俄羅斯的 banya 和芬蘭的桑拿很相似,但他們通常使用更高的溫度,並且會在蒸完後立即跳入冰冷的水中,感覺更刺激。而在日本,雖然沒有桑拿文化,但他們有 onsen(溫泉),依靠的是天然地熱。

Emma:的確,日本的溫泉文化受到火山活動的影響,而芬蘭和俄羅斯則需要自己創造熱源。芬蘭人能在沒有天然地熱資源的情況下把桑拿變成文化核心,這真的很了不起。

Julia:沒錯,這正是芬蘭桑拿文化的獨特之處。像冰島、日本甚至紐西蘭這些地方有天然溫泉,而芬蘭人卻得想辦法自創熱源。在某種程度上,這體現了他們在寒冷氣候中的韌性和創造力。

Emma:而隨著時間推移,桑拿也不僅僅是取暖的場所,更成了社交、放鬆甚至冥想的空間。真是有趣,一種針對寒冷的實用措施竟演變成了文化支柱。

Julia:這就是文化適應的絕佳例子。即便現在許多桑拿已從木柴改為電力加熱,桑拿依然深深根植於芬蘭人的身份中。

Emma and Julia continue their discussion about saunas at the café, delving into the differences between private and public saunas in Finland and comparing them with other bathing cultures.

Emma: So, are most saunas in Finland private, like in people’s homes, or are there public saunas where people gather, like the Roman baths?

Julia: Actually, it’s both. Many Finnish families have a sauna at home, and it’s a very private, almost sacred space for family bonding. But there are also public saunas, especially in cities and towns, where people can gather. It’s a social setting but usually a calm, respectful one.

Emma: That’s interesting. In ancient Rome, the bathhouses were more like social hubs. People would gather not only to bathe but to discuss politics, business, and daily life. It sounds like Finnish public saunas are a bit quieter, though.

Julia: Absolutely. The Finnish approach is more introspective. In a public sauna, people tend to speak in soft voices or even stay silent. It’s more about relaxation and inner peace than lively conversation. And unlike Roman baths, Finnish saunas are often gender-segregated, especially in public settings.

Emma: So there’s some privacy maintained, even in public saunas. That’s quite different from Turkish baths, for example, where men and women have separate spaces, but there’s still a lively atmosphere, especially with the scrubbing and massage rituals.

Turkish bathhouse

Julia: Right. Turkish baths, or hammams, are known for their communal rituals and physical care, like massages. But in Finland, sauna culture is more personal. Even when Finns share a sauna with strangers, there’s a kind of unspoken rule of respect and space. It’s common for families to have their private saunas, and many apartment buildings also have communal saunas that are used on a rotating schedule, sometimes with specific times for men and women.

Emma: That’s fascinating. So it’s a blend of communal and private traditions. I wonder if the need for quiet in Finnish saunas is connected to their cultural emphasis on personal space and introspection.

Julia: I think so. In Finnish culture, the sauna is almost a place of meditation. Even in mixed-gender saunas, which are more common in private family settings or among close friends, the focus is still on relaxation rather than socializing. It’s a stark contrast to the bustling, open spaces of Roman or Turkish baths.

Emma: And there’s no equivalent of the vigorous scrubbing you’d see in a hammam or the elaborate ritual structure of Roman baths, right?

Julia: Not at all. Finnish sauna rituals are quite simple: you heat up, you pour water on the stones to create steam, and then you might cool off with a plunge into cold water or snow. It’s an organic process, without the formality or specific procedures of other bath cultures.

Emma: I love that. It’s a minimalist approach, yet it holds so much meaning. It’s a place for Finns to unwind, and maybe even connect with nature in their own way, especially with that cold plunge.

Julia: Exactly. It’s about simplicity and being in tune with yourself and your surroundings. There’s no need for elaborate rituals—the warmth and the steam do the work, and that’s enough.

在咖啡館裡,Emma 和 Julia 繼續他們對桑拿文化的討論,深入比較芬蘭的桑拿與羅馬浴場、土耳其浴等沐浴文化的異同。

Emma:所以,在芬蘭大部分桑拿都是私人的嗎?比如在家裡用的,還是也有像羅馬浴場那樣的公共桑拿呢?

Julia:其實兩者都有。很多芬蘭家庭都有自己的私人桑拿,這是一個非常私密的空間,幾乎是一種家庭聯繫的神聖場所。但在城市和小鎮裡,也有公共桑拿,人們可以聚在一起。這是一種社交場合,但通常是平靜而尊重的氛圍。

Emma:這很有趣。在古羅馬,浴場更像是社交中心。人們不僅來這裡洗澡,還討論政治、商業和日常生活。聽起來芬蘭的公共桑拿要安靜得多。

Julia:沒錯。芬蘭的方式更為內省。在公共桑拿裡,人們通常低聲說話,甚至保持沉默。這更關於放鬆和內心的平靜,而不是熱烈的交談。而且與羅馬浴場不同的是,芬蘭的公共桑拿通常是男女分開的。

Emma:所以即使在公共桑拿裡,也有一些隱私。這與土耳其浴場很不一樣,土耳其浴場裡雖然男女分開,但氣氛仍然很熱鬧,特別是在揉搓和按摩儀式上。

Julia:沒錯。土耳其浴場,或者稱作 hammam,有很多的公共儀式和身體護理,比如按摩。而在芬蘭,桑拿文化更個人化。即使芬蘭人和陌生人一起蒸桑拿,也有一種默契的尊重和保持距離的規則。家庭一般會有自己的私人桑拿,而很多公寓樓也有共用桑拿,通常會安排特定的時間給男女分開使用。

Emma:真有趣,所以這是一種公共和私人傳統的融合。我想這種桑拿裡的安靜需求可能和芬蘭文化對個人空間和內省的重視有關。

Julia:我也這麼覺得。在芬蘭文化中,桑拿幾乎像是一個冥想的地方。即使在混合性別的桑拿中(通常是家庭或親密朋友間的),焦點仍然是放鬆,而不是社交。這與羅馬或土耳其浴場的熱鬧、開放空間形成鮮明對比。

羅馬浴場 (ancient Roman bathhouse)

Emma:而且沒有像土耳其浴場那樣的激烈揉搓,也沒有像羅馬浴場那樣的複雜儀式,是吧?

Julia:沒錯。芬蘭的桑拿儀式非常簡單:加熱、倒水在石頭上製造蒸汽,然後可能跳進冷水或雪裡降溫。這是一種自然的過程,沒有其他沐浴文化的正式禮節或特定程序。

Emma:我喜歡這種方式。這是一種極簡的方式,但卻蘊含著深厚的意義。這是讓芬蘭人放鬆的地方,甚至可以說是讓他們與自然聯繫的地方,特別是那種冷水的刺激。

Julia:就是這樣。它關於簡單和與自身及周圍環境的和諧。沒有必要的複雜儀式——熱氣和蒸汽就足夠了,這就是全部。

Setting: Emma and Julia are still in the cozy café, their conversation evolving into a deeper exploration of cultural and historical influences on sauna and bathing traditions.

Emma: Do you think the Finnish sense of introspection in the sauna has any roots in older traditions or even spiritual beliefs? It feels like there’s a meditative quality to it.

Julia: That’s an interesting question. The Finnish sauna experience does have a ritualistic feel, but it’s not directly tied to organized religion. Historically, though, Finns held nature in high regard, and the sauna was considered a kind of sacred space. It was the cleanest and warmest place in the house, so people treated it with a sense of reverence.

Emma: Almost like a connection to nature, then? I know some ancient cultures viewed nature as a powerful force—something to respect and coexist with, rather than dominate.

Julia: Exactly. The Finnish view of nature is very respectful. Sauna, in a way, embodies that connection. It’s a place where people can strip away distractions, both physically and mentally, and reconnect with something essential. That’s why Finns are so quiet and reflective in the sauna; it’s a space for self-reflection rather than socializing.

Emma: Fascinating. It’s almost the opposite of the Roman bathhouses, which were social hubs. Did you know that in ancient Rome, bathhouses weren’t just for bathing? People discussed politics, conducted business, and even shared meals there.

Julia: Yes, and from what I understand, the atmosphere in Roman baths was lively, almost the complete opposite of a Finnish sauna. Although, I did read that at some points, Roman baths allowed mixed-gender bathing, which must have been a bit awkward.

Emma: Oh, absolutely! They did sometimes allow men and women to bathe together, although it was controversial. Certain emperors, like Hadrian, even had to regulate it to prevent public discomfort. That’s such a stark contrast to Finnish saunas, where there’s a clear boundary in terms of personal space and gender separation in public saunas.

Julia: And unlike the Roman baths, Finnish saunas don’t have elaborate social rituals or gatherings. It’s about simplicity and introspection, which might be why Finns feel so connected to it. Even today, the sauna is seen as a personal sanctuary, a place to recharge spiritually, though it’s not linked to any specific religious practices.

Emma: That’s beautiful. It seems that, for Finns, the sauna offers a moment of peace that echoes their deep respect for the natural world. I guess the quietness and minimalism are part of that respect—no distractions, just being present.

Julia: Exactly. It’s a kind of spiritual tradition without being overtly religious. Finns find something sacred in the simplicity of the sauna, much like their ancestors might have seen nature as something to honor. That’s probably why it has remained such a meaningful part of Finnish life, even in modern times.

Emma 和 Julia 在咖啡館裡繼續討論,深入探討桑拿文化與芬蘭人內省習慣的關聯,以及是否與傳統和宗教信仰有關。

Emma:你覺得芬蘭人在桑拿中的內省習慣和舊有的傳統或是精神信仰有關嗎?感覺這裡面有種冥想的成分。

Julia:這是個有趣的問題。芬蘭的桑拿體驗確實帶有一種儀式感,但並不直接與宗教信仰相關。不過歷史上,芬蘭人對自然非常敬畏,桑拿被視為一種神聖的空間。它是屋內最乾淨和最溫暖的地方,所以人們對它有一種敬重之情。

Emma:那這就像是一種與自然的連結了?我知道一些古老文化把自然看作一種強大的力量——需要尊重和共存,而不是去征服。

Julia:沒錯。芬蘭人對自然的態度非常尊重。而桑拿在某種程度上體現了這種連結。它是一個讓人放下身心包袱、重新連結自我的地方。因此,芬蘭人在桑拿裡通常會很安靜和沉思,這是個內省的空間,而不是社交場所。

Emma:真有意思。這和羅馬浴場正好相反。你知道嗎,在古羅馬,浴場不僅僅是洗浴的地方,還是人們討論政治、進行商業交易甚至共餐的社交場所。

Julia:對,而且羅馬浴場的氣氛很熱鬧,這和芬蘭的桑拿完全相反。我還聽說羅馬浴場有時候允許男女共浴,這應該會有點尷尬吧。

Emma:是啊,確實如此!有時候他們會允許男女一起洗浴,但這在當時是很有爭議的。有些皇帝,比如哈德良,就頒布法令限制共浴,避免引起公眾的不適。這和芬蘭桑拿中的個人空間和公眾桑拿中男女分開的習慣形成了鮮明對比。

Julia:而且和羅馬浴場不同,芬蘭桑拿沒有複雜的社交儀式。它講究的是簡單和內省,這或許也是芬蘭人覺得與之相連的原因。即使在現代,桑拿仍然被視為一種個人的聖地,一個精神上充電的地方,但並不涉及任何具體的宗教儀式。

Emma:真是美妙。對芬蘭人來說,桑拿似乎提供了一個平靜的時刻,回應了他們對自然的深厚敬意。我想那種安靜和極簡風格也是出於這份敬意——沒有分心,僅僅是專注於當下。

Julia:沒錯。這是一種非宗教的精神傳統。芬蘭人從桑拿的簡單中找到了一種神聖感,這就像他們的祖先尊敬自然一樣。或許這就是為什麼即便在現代生活中,桑拿依然是芬蘭人生活中極具意義的一部分。

Religious History in Finland

Setting: Emma and Julia continue their discussion in the café, shifting their focus to Finland’s religious history and its influence on the culture.

Emma: It’s interesting that even though Finland is known for its introspective culture, it doesn’t have the same intense religious presence as some other European countries. Do you know much about the main religion here?

Julia: Yes, Finland has a unique religious history. The majority of Finns are Lutheran, specifically part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, which has deep roots here. This was largely due to Swedish influence during the centuries when Finland was under Swedish rule.

Emma: So the Lutheran faith really shaped the culture, I imagine. Lutherans have a reputation for simplicity and a focus on individual spirituality rather than grand rituals, which seems to align with Finnish values.

Julia: Exactly. Lutheranism, with its emphasis on humility, modesty, and personal reflection, resonated well with the Finnish mindset. In fact, even though a large part of the population is still officially Lutheran, regular church attendance is quite low. Finns tend to approach religion in a quiet, personal way, rather than as a public expression.

Emma: That makes sense. There’s something very introspective about the Finnish culture overall. I suppose that’s why traditions like the sauna, which is deeply personal and meditative, fit so well here, even though it’s not religious.

Julia: Right. Sauna is a good example of that. Although it’s not tied to the church, it still has that same quiet, contemplative quality. And it’s interesting to think about how this approach to spirituality compares to the influence of Orthodoxy in neighboring Russia. Orthodoxy is much more visual and ceremonial.

Emma: That’s true. Orthodox churches are filled with icons, candles, and elaborate rituals. It’s a very sensory experience, whereas Finnish churches—even their old cathedrals—are relatively simple and understated. I guess that contrast reflects Finland’s historical balance between East and West.

Julia: Definitely. Finland’s location has always put it at a cultural crossroads. While the western part of the country leaned towards Sweden and Lutheranism, the eastern regions near Russia had more Orthodox influence. Even today, Orthodox Christianity is a minority religion here, especially in the eastern parts.

Emma: So there’s a subtle mix of traditions. That might explain why Finns seem to approach spirituality in a very individual way, without a lot of outward displays. It’s like they value the inner experience over the external show.

Julia: Yes, and that’s also why many Finns identify as spiritual but not necessarily religious. There’s an appreciation for nature, quietude, and a sort of everyday mindfulness that fills that space without needing formal religion. It’s a quiet reverence, whether in the forests, by the lakes, or in the sauna.

Emma: It’s beautiful, really—a kind of spirituality rooted in simplicity and presence. I think that gives Finnish culture a unique sense of peace.

芬蘭的宗教歷史

場景:Emma 和 Julia 在咖啡館裡繼續討論,話題轉向芬蘭的宗教歷史及其對當地文化的影響。

Emma:有趣的是,芬蘭雖然以內省文化著稱,但宗教影響力似乎不像一些其他歐洲國家那麼強。你知道這裡的主要宗教是什麼嗎?

Julia:是的,芬蘭的宗教歷史很獨特。大多數芬蘭人信仰路德宗,特別是芬蘭福音路德教會,這和芬蘭長期被瑞典統治有很大關係,瑞典傳來的路德宗深深影響了這裡。

Emma:我想路德宗確實對這裡的文化影響很大。路德宗強調簡樸和個人的靈性,而不是盛大的儀式,這似乎也與芬蘭的價值觀很契合。

Julia:沒錯。路德宗的謙卑、低調和自省理念非常適合芬蘭人的思維方式。其實,雖然大部分人名義上還是路德宗教徒,但真正參加教堂禮拜的並不多。芬蘭人對宗教的態度更多是安靜和個人的,而不是公開的表達。

Emma:這就說得通了。整體而言,芬蘭文化確實非常內省。我想這也是為什麼像桑拿這樣的傳統在這裡那麼受歡迎,因為它是一種個人和冥想的體驗,雖然不具有宗教性質。

Julia:對,桑拿就是很好的例子。雖然與教會無關,但它同樣具有安靜和沉思的特質。有趣的是,這種靈性觀和俄羅斯的東正教影響形成了鮮明對比。東正教更注重視覺上的莊嚴和儀式感。

Emma:沒錯。東正教堂內充滿了聖像、蠟燭和華麗的儀式,是一種很感官的體驗,而芬蘭的教堂——即使是古老的大教堂——相對簡樸低調。我猜這種對比反映了芬蘭在東西方之間的歷史平衡。

Julia:的確如此。芬蘭的地理位置讓它成為東西方文化的交匯點。西部偏向瑞典和路德宗,而靠近俄羅斯的東部則受東正教影響較多。直到今天,東正教仍是芬蘭的少數宗教,特別是在東部地區。

Emma:所以這裡有著微妙的傳統融合。這可能解釋了為什麼芬蘭人對靈性有著非常個人的詮釋,而不是外在的展示。他們似乎更重視內心的體驗,而不是外在的表現。

Julia:是的,這也是為什麼很多芬蘭人自稱是“精神信仰者”而非“宗教信徒”。他們對大自然、寧靜和一種日常的專注充滿敬意,這種精神信仰不需要正式的宗教形式。無論是在森林、湖邊,還是在桑拿裡,都可以體會到這種寧靜的敬畏。

Emma:這真是美好——一種根植於簡樸和當下的靈性。我覺得這賦予了芬蘭文化一種獨特的平和感。

發表留言