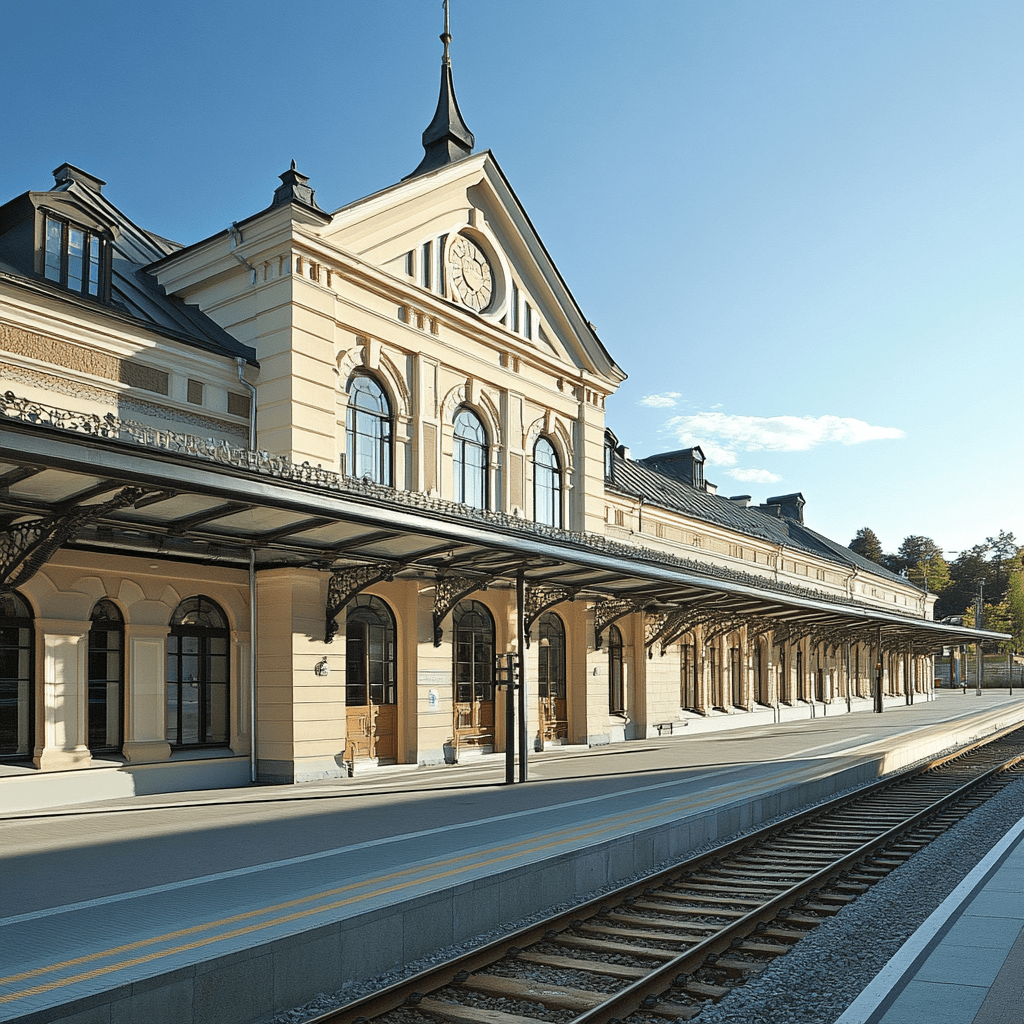

At the Turku Train Station

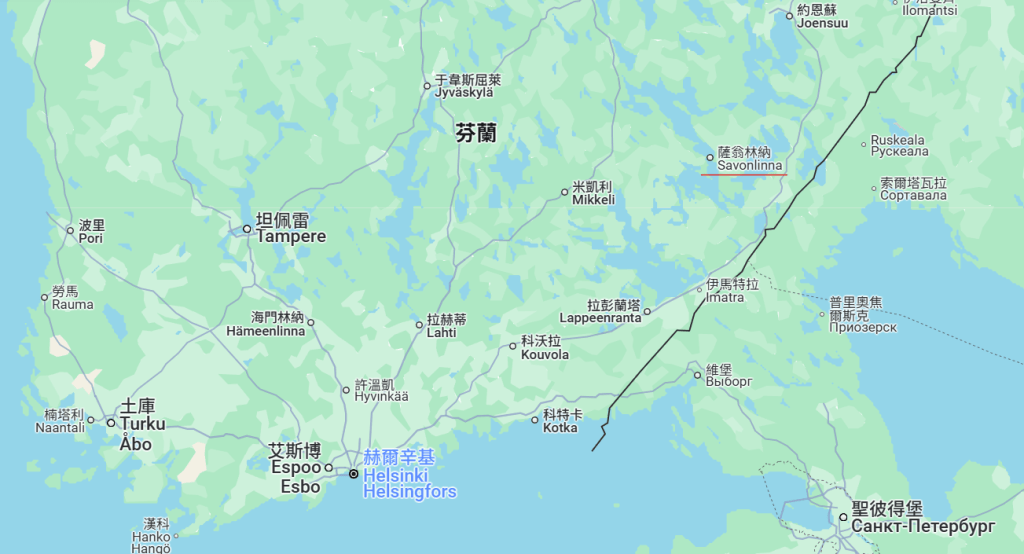

Emma and Julia arrive at the Turku train station, a mix of modern design and historical touches. The platform is surrounded by well-maintained greenery, and the bright summer sun adds warmth to the otherwise minimalist Scandinavian architecture. Their train to Savonlinna is ready to depart, promising a scenic journey through Finland’s countryside

Emma: This station is so clean and efficient. It’s almost minimalist but still welcoming.

Julia: That’s very Finnish, isn’t it? Functionality above all else. Finnish trains are known for their punctuality and comfort. It’ll be about five and a half hours to Savonlinna, but the views should make it feel much shorter.

Emma: I’ve read that Finnish railways are some of the best in Europe for scenic routes. And they’re electrified, right?

Julia: Yes, most of them. It’s all part of Finland’s commitment to sustainability. But imagine traveling through these landscapes in the 15th century—no railways, just boats and rough trails. The waterways were the lifeblood of Finland back then.

Emma: That’s fascinating. In the 15th century, Finland was under Swedish rule, wasn’t it? It must have been a very different kind of life.

Julia: Absolutely. Finland didn’t have its own centralized government or kingdom at that time. It was part of the Swedish realm, essentially serving as a buffer zone between Sweden and Novgorod, which was later absorbed into Russia.

Emma: A buffer zone—so, not exactly a priority for the Swedes?

Julia: Not at all. For Sweden, Finland was more about strategic value than cultural integration. The Finns largely retained their own language and customs, but the ruling elite were Swedish, and Swedish was the official language.

Emma: That must have created quite a divide. Did the Finns ever push for independence back then?

Julia: Not in the medieval period. Finland’s population was relatively small and scattered, and the idea of nation-states as we know them today didn’t exist yet. Most Finns were peasants, focused on survival rather than politics.

Emma: So, Finland wasn’t really “Finland” yet. It was just a region of Sweden.

Julia: Exactly. It’s a fascinating period because, while Finland didn’t have its own sovereignty, its geography—especially those waterways—shaped its role in the broader conflicts between Sweden and Russia.

Emma: That explains why castles like Olavinlinna were so important. They weren’t just for defense—they were symbols of control over the land.

Julia: And over the people. The 15th century was a time of constant negotiation, with Finland caught between these larger powers. It wasn’t until much later, in the 19th century, that Finland started developing a stronger national identity.

在圖爾庫火車站

Emma 和 Julia 抵達圖爾庫火車站,車站結合了現代設計與歷史元素。月台周圍是精心維護的綠化,明亮的夏日陽光為簡約的北歐建築增添了一絲溫暖。他們準備乘火車前往薩翁林納,途經芬蘭的鄉村美景。

Emma:這個車站真乾淨高效。簡約中又很有親和力。

Julia:這很芬蘭,不是嗎?功能性優先。芬蘭的火車以準時和舒適著稱。我們到薩翁林納大約要五個半小時,但沿途的景色應該會讓時間過得很快。

Emma:我聽說芬蘭的鐵路是歐洲最適合欣賞風景的之一。而且是電氣化的,對吧?

Julia:是的,大部分都是,這也是芬蘭致力於可持續發展的一部分。但你能想像15世紀時穿越這些景色嗎?當時沒有鐵路,只有船隻和崎嶇的小路。那時候水路是芬蘭的生命線。

Emma:真有意思。15世紀時,芬蘭是瑞典統治下的,對吧?那時的生活一定完全不同。

Julia:確實如此。當時芬蘭並沒有自己的中央政府或王國,基本上是瑞典王國的一部分,充當瑞典和諾夫哥羅德之間的緩衝地區,後來諾夫哥羅德成為了俄羅斯的一部分。

Emma:緩衝地區——所以對瑞典來說並不是優先考量的地方?

Julia:一點也不。對瑞典而言,芬蘭的價值主要在於戰略意義,而不是文化融合。芬蘭人大多保留了自己的語言和習俗,但統治精英是瑞典人,瑞典語是官方語言。

Emma:那肯定造成了很大的分歧。當時的芬蘭人有推動獨立的念頭嗎?

Julia:在中世紀並沒有。當時芬蘭的人口相對較少且分散,而且我們今天理解的民族國家概念還不存在。大多數芬蘭人是農民,關注的更多是生存,而不是政治。

Emma:所以那時候的芬蘭並不是真正意義上的“芬蘭”,更像是瑞典的一個地區。

Julia:沒錯。那是一個有趣的時期,儘管芬蘭沒有自己的主權,但其地理位置——特別是那些水路——決定了它在瑞典與俄羅斯之間的衝突中扮演的角色。

Emma:這也解釋了為什麼像奧拉維城堡這樣的地方如此重要。它們不僅是防禦工事,也是控制土地的象徵。

Julia:同時也是對人民的控制。15世紀是一個充滿談判的時代,芬蘭處在這些大國之間。直到19世紀,芬蘭才開始發展出更強的民族認同感。

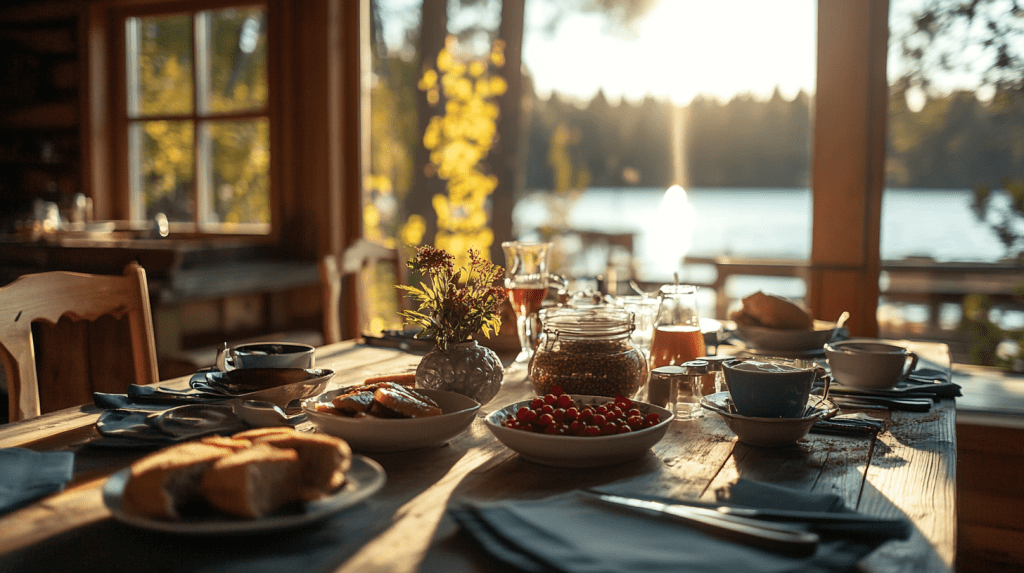

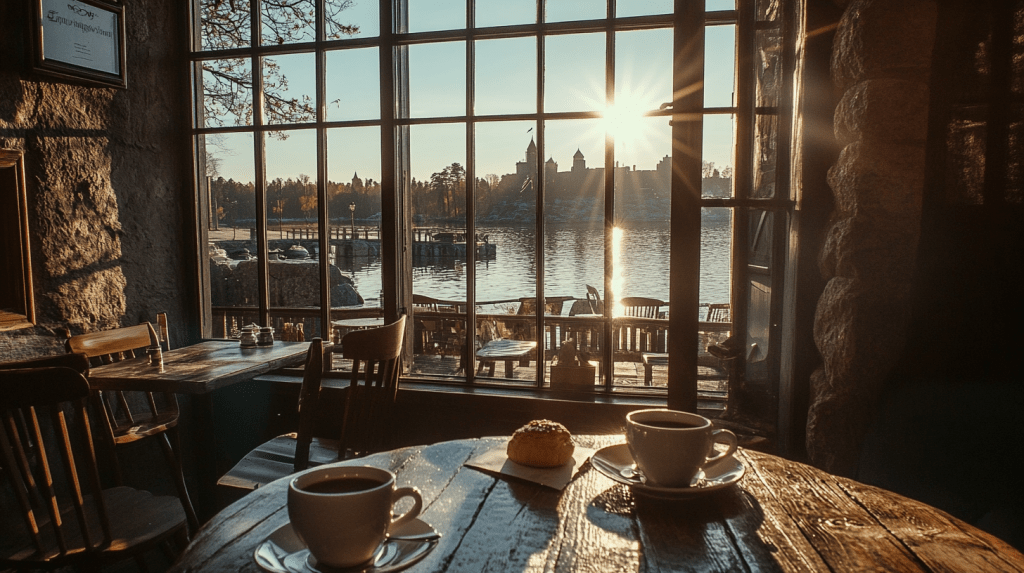

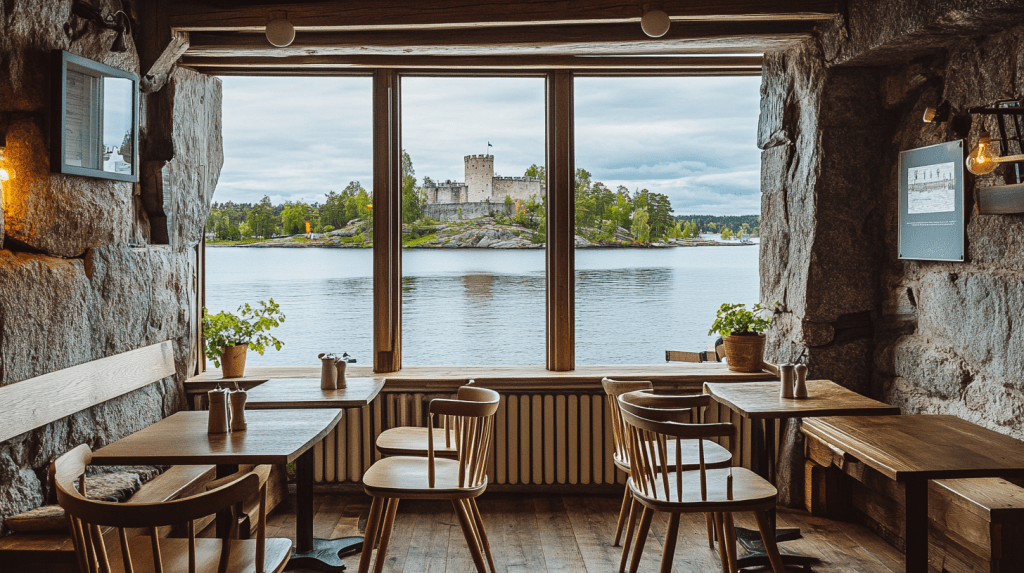

In a Lakeside Inn: Exploring Finnish Cuisine

Emma and Julia are seated in the dining area of their lakeside inn. The room has large windows overlooking the calm lake, and the setting sun bathes the space in a golden glow. A waiter brings a platter of traditional Finnish dishes to their table, sparking a deeper conversation.

Emma: The lake looks so tranquil. It’s hard to imagine how cold it gets here in winter.

Julia: Surprisingly, winters here aren’t as harsh as in the north, but they’re still cold by most standards. Savonlinna is in the southern part of Finland, so the lakes freeze over, but temperatures don’t drop as low as in Lapland.

Emma: So it’s more moderate compared to the Arctic north. Does that affect the food here?

Emma picks up a piece of smoked fish from the platter.

Julia: Definitely. Fish is a staple across Finland, but the types vary by region and season. This smoked fish is probably lake trout or Arctic char, both common in these parts. In summer, you might also find perch or pike, which are caught in the nearby lakes.

Emma: That’s interesting. And the smoking—does it preserve the fish for the colder months?

Julia: Exactly. Smoking has been a traditional method of preservation for centuries, especially in regions like this where fishing is seasonal. Even now, it’s as much about flavor as it is about practicality.

Emma: The flavor is incredible—rich but not overwhelming. Do you think this preparation is unique to Finland?

Julia: It’s distinctively Finnish in its simplicity. While neighboring countries like Sweden and Norway also smoke fish, Finnish methods tend to focus more on the natural taste of the fish itself, without too many spices or marinades.

Emma glances at the berries on the platter.

Emma: And these berries—are they seasonal too?

Julia: Absolutely. These are bilberries, closely related to blueberries but with a more intense flavor. In summer, you’d also find lingonberries, cloudberries, and raspberries. Finns love foraging for berries during the warmer months—it’s practically a national pastime.

Emma: That’s fascinating. It seems like the cuisine here really reflects the environment—seasonal, local, and minimal waste.

Julia: It does. Even the bread, like this rye bread, is designed to be hearty and sustaining, perfect for a climate that can be unpredictable.

Emma looks out the window at the lake, now tinged with the pink hues of sunset.

Emma: It’s amazing how much of Finland’s culture is tied to nature. Even the food feels like a direct connection to the landscape.

湖畔旅館:探索芬蘭傳統美食

Emma 和 Julia 坐在湖邊旅館的餐廳裡。房間裡有大片窗戶,正對著寧靜的湖面。夕陽將整個空間染上金色,服務員端上一盤芬蘭傳統菜餚,兩人展開了深入的討論。

Emma:這湖面真安靜。很難想像冬天這裡有多冷。

Julia:其實這裡的冬天不像北邊那麼嚴酷,但對大多數人來說還是很冷。薩翁林納位於芬蘭南部,所以湖會結冰,但溫度不會像拉普蘭那麼低。

Emma:所以相對於北極圈以北,這裡的氣候要溫和一些。那這會影響這裡的食物嗎?

Emma 拿起盤中的一塊熏魚。

Julia:肯定會。魚是芬蘭飲食的主角,但種類因地區和季節而異。這塊熏魚應該是湖鱒魚(lake trout)或者北極紅點鮭(Arctic char),這兩種魚在這裡很常見。夏天的話,你還可能吃到鱸魚(perch)或狗魚(pike),它們通常在附近的湖裡捕撈。

Emma:這很有趣。那熏製是為了保存魚,方便冬天食用嗎?

Julia:沒錯。熏製是這裡幾個世紀以來的傳統保存方法,特別是在像這樣捕魚有季節性的地方。即使現在,熏製魚更多是為了味道,但保鮮的意圖仍然存在。

Emma:味道真的很棒——濃郁卻不膩。你覺得這種做法在芬蘭特別獨特嗎?

Julia:芬蘭的熏魚講究的是簡單直接。雖然瑞典和挪威也有熏魚,但芬蘭的方法更注重魚本身的自然風味,通常不會加太多香料或醃料。

Emma 看了一眼盤中的莓果。

Emma:這些莓果也是季節性的嗎?

Julia:完全正確。這是藍莓的一種,但味道比普通藍莓更濃郁。夏天你還會看到越橘(lingonberries)、雲莓(cloudberries)和覆盆子(raspberries)。芬蘭人特別喜歡在夏季去森林裡採集莓果,這幾乎成了一種全民愛好。

Emma:真有趣。這裡的飲食似乎完全反映了環境的特性——季節性、本地化,並且沒有浪費。

Julia:確實如此。就連這黑麥麵包,也是為了適應寒冷氣候而設計的,營養又耐儲存,非常實用。

Emma 望向窗外,此時湖面已被粉色的晚霞染上了一層柔光。

Emma:真令人驚嘆。芬蘭的文化似乎與自然緊密相連,就連食物都像是直接從這片土地上汲取靈感。

Emma and Julia sat in the dining area of their lakeside inn, gazing at the serene lake through the large windows. A waiter brought over a platter of traditional Finnish dishes, and the two began discussing the occupations and lifestyles of the local residents while enjoying their meal.

Emma: Sitting here, looking out at the lake, I can’t help but wonder—what do people around here do for a living? This area feels so peaceful and removed from the hustle of city life.

Julia: Historically, the people of Savonlinna depended heavily on the lake and the surrounding forests. Fishing was a major source of income, along with logging and small-scale farming.

Emma: That makes sense, given the abundance of natural resources. But I imagine life wasn’t easy.

Julia: It wasn’t. Finland was under Swedish rule for centuries, and later under Russian control. During those times, many Finns were subsistence farmers or laborers, often struggling to make ends meet. The harsh winters and the demands of foreign rulers didn’t help.

Emma: It’s remarkable how Finland transformed itself. From being a nation under foreign rule to becoming one of the most advanced countries in education and technology.

Julia: Absolutely. After gaining independence in 1917, Finland focused heavily on education as a way to rebuild and empower its people. That’s why even in rural areas like this, there’s such pride in the school system.

Emma: So, what about now? Are fishing and forestry still significant here?

Julia: To some extent, yes, but the economy has diversified. Tourism is a big part of life in Savonlinna, thanks to attractions like Olavinlinna Castle and Lake Saimaa. Many locals work in the hospitality industry. At the same time, Finland’s push for innovation means even small towns like this benefit from technology-driven businesses.

Emma: It’s fascinating how the balance has shifted. From relying on nature for survival to leveraging it for tourism and sustainable living.

Emma 和 Julia 坐在湖邊旅館的餐廳中,透過窗戶可以看到寧靜的湖面。服務員端上來一盤芬蘭傳統菜餚,兩人邊用餐邊討論當地居民的職業和生活方式。

Emma:坐在這裡看著湖面,我不禁好奇,這附近的人平時都做什麼工作?這裡感覺遠離城市的喧囂,生活應該很平靜吧。

Julia:歷史上,薩翁林納的居民主要依靠湖泊和周圍的森林謀生。捕魚是重要的收入來源,還有伐木和小規模的農耕。

Emma:這很合理,這裡的自然資源非常豐富。不過,我猜生活應該並不輕鬆吧?

Julia:確實如此。芬蘭曾經長期被瑞典統治,後來又被俄羅斯控制。在那段時期,很多芬蘭人都是自給自足的農民或工人,經常過著艱難的生活。嚴寒的冬天和外來統治者的壓迫讓生活更加困難。

Emma:芬蘭的轉變真的很了不起。從一個被外國統治的國家,變成如今教育和科技都卓越的國家。

Julia:沒錯。芬蘭在 1917 年獨立後,就非常重視教育,把它作為重建和提升國民力量的方式。即使在像這樣的鄉村地區,人們對學校系統也有很強的自豪感。

Emma:那現在呢?這裡的人還依賴捕魚和林業嗎?

Julia:一定程度上還是有的,但經濟已經多樣化了。薩翁林納的旅遊業很發達,像奧拉維城堡和塞馬湖這樣的景點吸引了很多遊客,很多當地人從事酒店和旅遊相關的工作。同時,芬蘭的創新政策也讓像這樣的小鎮受益於科技驅動的企業。

Emma:這種平衡真的很有趣。從依賴自然資源生存,到將其用於旅遊和可持續發展,完全是一種轉變。

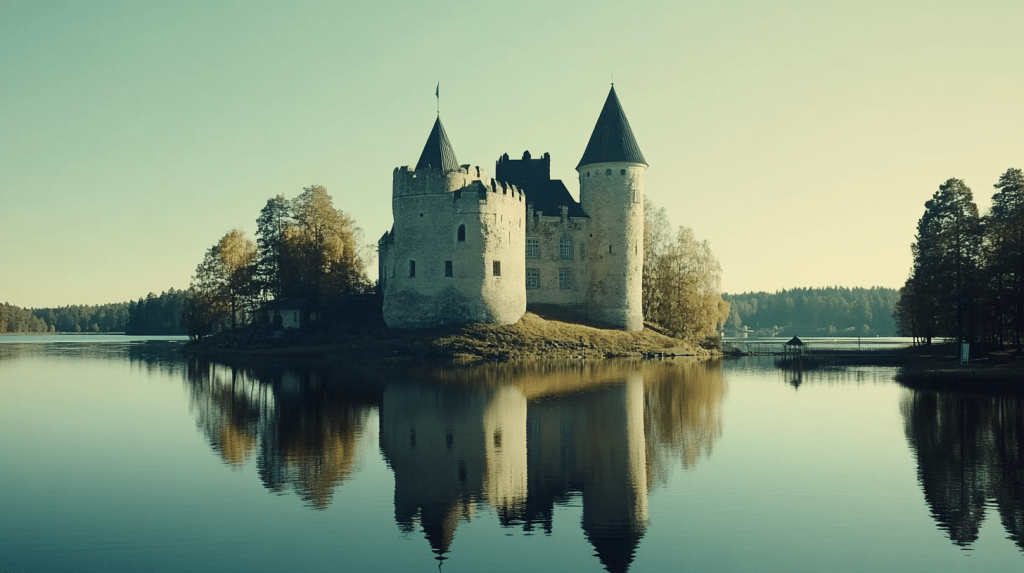

Olavinlinna: A Fortress Amid the Struggles of Sweden, Finland, and Russia

Emma and Julia stood atop the defensive tower of Olavinlinna Castle, overlooking the surrounding Lake Saimaa and its islands. A gentle breeze brushed past them as their conversation gradually turned to the castle’s historical role in geopolitics and Finland’s position within it.

Emma: Looking out from here, it’s hard not to imagine how strategic this location must have been. Sweden, Finland, Russia—this place embodies centuries of conflict and shifting power.

Julia: That’s exactly right. For much of the medieval and early modern periods, Finland was under Swedish rule. Sweden viewed Finland as its eastern frontier—a crucial buffer against Russian expansion.

Emma: So Finland wasn’t its own nation then, but more of a battleground?

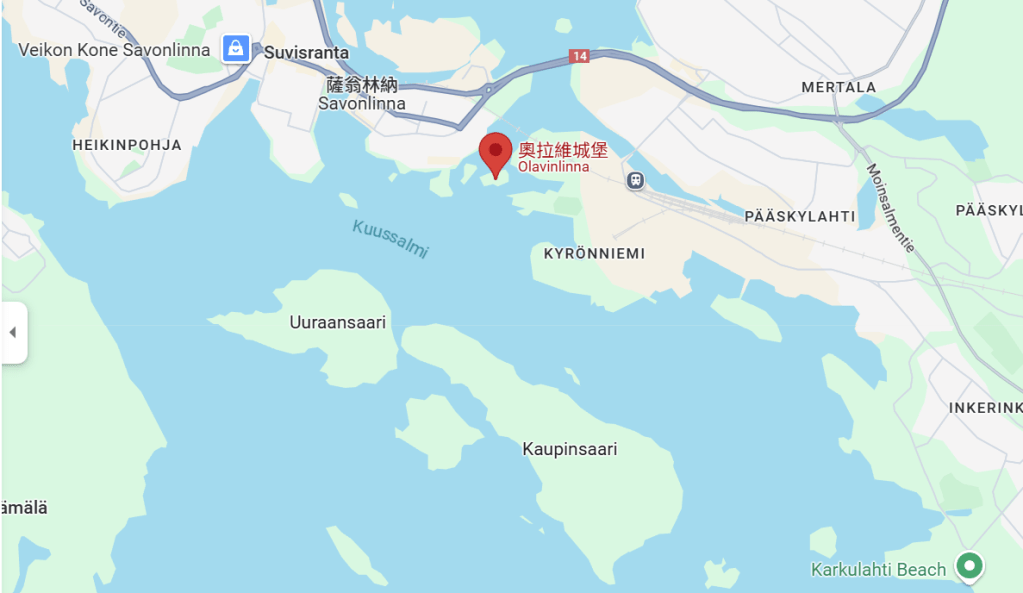

Julia: Precisely. Finland’s geographical location made it a contested space between Sweden and Russia. This castle, Olavinlinna, was built in 1475 by Erik Axelsson Tott to fortify Sweden’s control over eastern Finland and protect against the Grand Duchy of Moscow’s ambitions.

Emma: It makes sense strategically—this castle, surrounded by water, must have been nearly impregnable. Did it see much action?

Julia: Oh, absolutely. This region was the site of numerous Russo-Swedish wars. One of the most notable events was the Siege of Olavinlinna in 1656, during the Russo-Swedish War. Russian forces tried to capture the castle but ultimately failed due to its strong defenses and Sweden’s military presence.

Emma: And after that? Did the balance of power shift?

Julia: Over time, yes. By the 18th century, Russia’s influence was growing. The pivotal moment came during the Great Northern War (1700–1721). After Sweden’s defeat, Russia gained control of much of Finland’s eastern territory. Eventually, in 1809, Finland was ceded entirely to Russia and became the Grand Duchy of Finland.

Emma: That must have been a significant change for the Finnish people. What was life like under Russian rule compared to Swedish rule?

Julia: It was complicated. Under Swedish rule, Finnish people were largely treated as second-class citizens, expected to pay taxes and serve in the Swedish army. While they gained some autonomy under Russian rule, it came with increased cultural pressure, as Russia tried to Russify Finland.

Emma: Russify? How so?

Julia: For instance, the Russian authorities pushed for the use of the Russian language in administration and education. However, the Finns resisted, and this period also saw the emergence of Finnish nationalism. Ironically, the cultural suppression fueled a stronger sense of Finnish identity.

Emma: That’s fascinating. So, Finland’s identity was forged through resistance?

Julia: In many ways, yes. Despite centuries of foreign domination, Finnish culture and language persisted. By the time Finland declared independence in 1917, it had already developed a unique identity distinct from both Sweden and Russia.

Emma: It’s remarkable to think about the resilience of the Finnish people. They’ve turned centuries of being a buffer zone into a strength.

Julia: And places like Olavinlinna are tangible reminders of that history. What was once a military fortress is now a symbol of cultural pride and resilience.

奧拉維城堡:見證瑞典、芬蘭與俄羅斯的紛爭與轉變

Emma 和 Julia 站在奧拉維城堡的防禦塔上,俯瞰四周的塞馬湖與群島。微風輕拂,夕陽映照在水面上,他們的話題漸漸轉向城堡在地緣政治中的歷史角色,以及瑞典、芬蘭與俄羅斯的關係。

奧拉維城堡:見證瑞典、芬蘭與俄羅斯的紛爭與轉變

Emma:站在這裡,真的讓人感覺這座城堡的位置有多重要。瑞典、芬蘭、俄羅斯……這裡彷彿記錄了三國之間幾個世紀的紛爭。

Julia:是啊。中世紀和早期近代時期,芬蘭一直是瑞典的領土。對瑞典來說,芬蘭是它的東部邊界,也是抵禦俄羅斯擴張的重要屏障。

Emma:所以,芬蘭當時不是一個獨立的國家,而是更像一個戰場?

Julia:可以這麼說。芬蘭的地理位置讓它成為瑞典與俄羅斯之間的爭奪之地。這座奧拉維城堡是 1475 年由瑞典貴族 Erik Axelsson Tott 建造的,目的是加強瑞典對芬蘭東部的控制,同時抵禦當時莫斯科大公國的威脅。

Emma:從這個角度看,城堡的設計真的很合理。被水環繞,幾乎固若金湯。這裡經歷過很多戰爭嗎?

Julia:當然。這裡曾是多次瑞典與俄羅斯戰爭的重要戰場。例如在 1656 年的奧拉維城堡圍城戰中,俄羅斯軍隊試圖攻佔這裡,但最終失敗,因為城堡的防禦太強大,而瑞典軍隊的增援也很及時。

Emma:那後來呢?力量平衡有改變嗎?

Julia:確實改變了。18 世紀,俄羅斯的影響力逐漸上升。特別是在大北方戰爭(1700–1721)期間,瑞典被擊敗,俄羅斯獲得了芬蘭東部的控制權。最終,1809 年芬蘭被整個割讓給俄羅斯,成為芬蘭大公國的一部分。

Emma:對芬蘭人民來說,從瑞典轉到俄羅斯統治,生活有什麼不同嗎?

Julia:這是一個複雜的問題。在瑞典統治下,芬蘭人多半是二等公民,要繳納高額稅收,還要為瑞典軍隊服役。而在俄羅斯統治下,雖然芬蘭獲得了一定的自治權,但也面臨文化上的壓力,俄羅斯當局試圖推行「俄化政策」。

Emma:俄化政策?是怎麼樣的?

Julia:例如,要求在行政和教育中使用俄語,而不是芬蘭語。然而,芬蘭人強烈抵制這些政策,這段時期反而激發了芬蘭民族主義的興起。

Emma:真有趣,芬蘭的民族身份反而是在抗爭中形成的。

Julia:是的。儘管幾個世紀以來一直被外國統治,芬蘭文化和語言從未消亡。1917 年芬蘭宣布獨立時,已經形成了一個獨特的民族身份,與瑞典和俄羅斯都不同。

Emma:這真是令人欽佩的韌性。芬蘭人民把自己從緩衝地帶的角色轉化為一種力量。

Julia:沒錯,而像奧拉維城堡這樣的地方,不僅是歷史的見證,也是文化驕傲和民族韌性的象徵。

From Domination to Independence: Finland’s Journey to Nationhood

Emma and Julia sit in the courtyard of Olavinlinna Castle, surrounded by its thick stone walls and medieval atmosphere. Their discussion shifts from the history of the castle to how Finland evolved from a long-ruled territory into an independent nation.

Emma: It’s incredible to think that Finland was once a battleground between Sweden and Russia, and now it’s an independent nation. That journey must have been transformative.

Julia: It certainly was. Finland’s road to independence in 1917 was shaped by centuries of foreign domination, economic challenges, and cultural resilience. Each period of foreign rule left its mark, and the differences between Swedish and Russian influences are particularly striking.

Emma: How so? What was Finland like under Swedish rule compared to Russian rule?

Julia: Under Swedish rule, which lasted from the 12th century to 1809, Finland was seen as a peripheral territory. The Swedish crown imposed its legal and religious systems, including Lutheranism, but Finnish people were often treated as second-class citizens. Swedish was the language of the elite and administration, while Finnish was spoken primarily by peasants.

Emma: So, Swedish rule wasn’t exactly inclusive.

Julia: No, but it did bring some stability. The Swedish legal system, for example, laid the foundation for property rights and governance. However, when Finland became a Grand Duchy of Russia in 1809, things shifted dramatically.

Emma: How did Russian rule differ?

Julia: The Russians allowed Finland a surprising degree of autonomy, including its own legal system and Lutheran church. This period also saw the rise of Finnish nationalism. Figures like Johan Ludvig Runeberg and Elias Lönnrot celebrated Finnish culture, language, and folklore, fostering a sense of identity distinct from both Sweden and Russia.

Emma: That’s fascinating—so, Russian rule unintentionally nurtured Finnish nationalism?

Julia: Exactly. But this autonomy came under threat during the late 19th century when Russia began a policy of Russification. Finnish institutions were targeted, and the use of Russian in administration was enforced. This created tension and resistance, which fueled the independence movement.

Emma: And by 1917, Finland was ready to break free?

Julia: Yes, but the timing was critical. The Russian Revolution created a power vacuum, allowing Finland to declare independence. However, the journey wasn’t smooth—there was a civil war in 1918 between the Red and White factions, representing socialist and conservative forces.

Emma: That must have been a challenging start for a new nation.

Julia: It was. Economically, Finland was still largely agrarian, but the interwar period saw significant industrialization and modernization. Politically, the nation embraced democracy, with universal suffrage granted as early as 1906—one of the first countries to do so.

Emma: That’s remarkable progress. How did Finland balance its cultural identity between Swedish and Russian influences?

Julia: By emphasizing its own distinct heritage. The Finnish language gained official status, and the Kalevala, Finland’s national epic, became a symbol of cultural pride. Education played a huge role too—promoting literacy and civic values in Finnish.

Emma: And today, Finland feels completely distinct from both Sweden and Russia.

Julia: Absolutely. Finland’s path to independence is a testament to its resilience and ability to adapt while preserving its identity. It’s a small country that learned how to assert itself in a challenging geopolitical landscape.

從統治到獨立:芬蘭建國之路

Emma:很難想像,芬蘭曾經是瑞典和俄羅斯之間的戰場,而現在卻是一個獨立的國家。這個過程一定很不簡單吧?

Julia:的確如此。芬蘭在 1917 年宣布獨立的過程,受到了幾個世紀外國統治、經濟挑戰以及文化韌性的影響。瑞典和俄羅斯對芬蘭的統治方式也有很大的不同。

Emma:怎麼不同?瑞典統治和俄羅斯統治下的芬蘭有什麼差別?

Julia:瑞典統治從 12 世紀一直持續到 1809 年,芬蘭在瑞典王國中被視為一個邊緣地區。瑞典王室引入了法律體系和宗教,尤其是路德教,但芬蘭人經常被當作二等公民對待。瑞典語是精英和行政的語言,而芬蘭語主要是農民的語言。

Emma:所以,瑞典統治並不算包容吧?

Julia:是的,但它帶來了一些穩定性,比如瑞典的法律體系為財產權和治理奠定了基礎。不過,1809 年芬蘭成為俄羅斯的大公國後,情況發生了巨大變化。

Emma:俄羅斯統治又是怎樣的?

Julia:俄羅斯給了芬蘭相當大的自治權,包括保留自己的法律體系和路德教會。這段時期也見證了芬蘭民族主義的興起。像魯內貝里(Johan Ludvig Runeberg)和倫羅特(Elias Lönnrot)這樣的人物,通過讚美芬蘭的文化、語言和民間故事,培養了一種獨特的民族認同感。

Emma:真有趣,所以俄羅斯統治反而無意中滋養了芬蘭的民族主義?

Julia:正是如此。但到了 19 世紀末,俄羅斯開始推行「俄化政策」,試圖削弱芬蘭的自治,這包括在行政中強制使用俄語。這種文化壓力引發了強烈的反抗,最終推動了獨立運動的進一步發展。

Emma:那麼到了 1917 年,芬蘭真的準備好獨立了嗎?

Julia:是的,但時機非常關鍵。俄羅斯革命造成了權力真空,芬蘭抓住機會宣布獨立。不過,隨後在 1918 年爆發了一場內戰,紅軍(社會主義派)和白軍(保守派)之間的衝突使國家面臨了艱難的開端。

Emma:對一個新生的國家來說,這一定很不容易吧?

Julia:是的。當時芬蘭仍然以農業為主,但在兩次世界大戰之間,工業化和現代化的進程非常迅速。在政治上,芬蘭實行民主制度,並在 1906 年就實現了普選權,是世界上最早做到這一點的國家之一。

Emma:這進步真令人驚嘆。那芬蘭是如何在瑞典和俄羅斯的影響之間找到自己的文化身份的呢?

Julia:通過強調自身的遺產。芬蘭語獲得了官方地位,而《卡勒瓦拉》(芬蘭民族史詩)則成為文化自豪感的象徵。教育在這方面也發揮了重要作用,提升了全民識字率,並推動公民價值的普及。

Emma:而現在的芬蘭感覺完全與瑞典和俄羅斯不同了。

Julia:沒錯。芬蘭的獨立道路是一個韌性與適應能力的故事。這是一個小國,在艱難的地緣政治環境中學會了如何捍衛自己的位置。

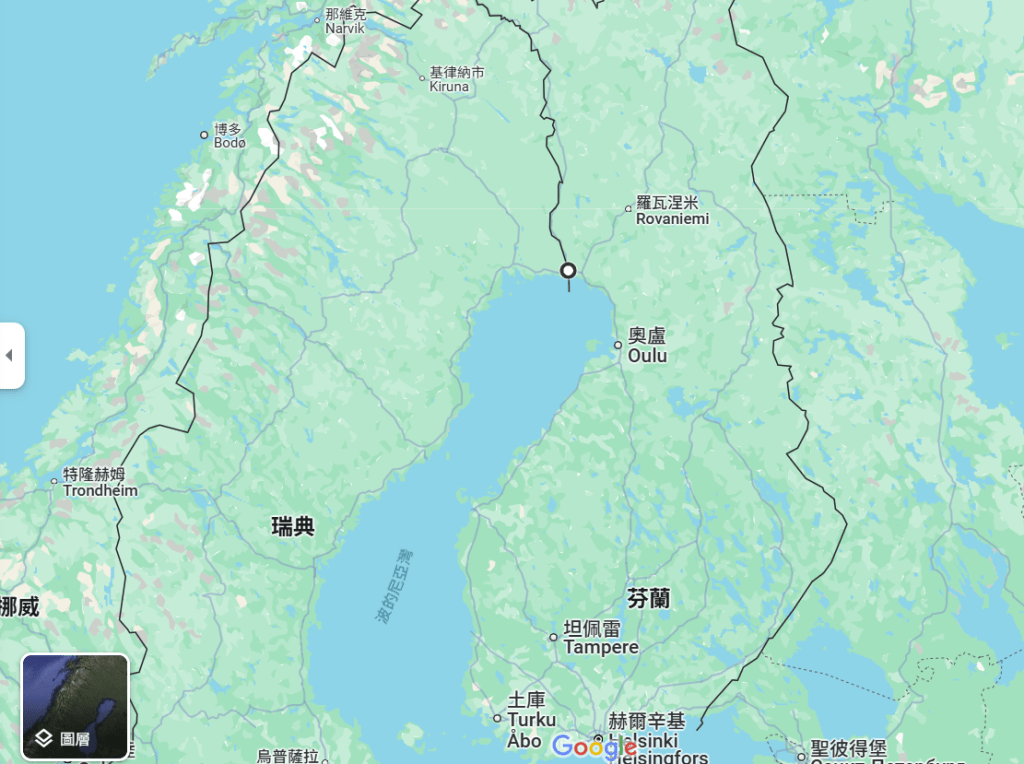

Shaped by the Earth: Geology, Economy, and Society in Scandinavia

Emma and Julia sit atop the tower of Olavinlinna Castle, overlooking the magnificent view of Lake Saimaa. Their conversation shifts from Finland’s mineral resources to the geological features of the three Scandinavian countries and how these characteristics have shaped their respective economies, cultures, and social policies.

Emma: Sitting here and looking at Finland’s vast forests and lakes, I can’t help but wonder—how did Finland manage its resources compared to its neighbors like Sweden and Norway?

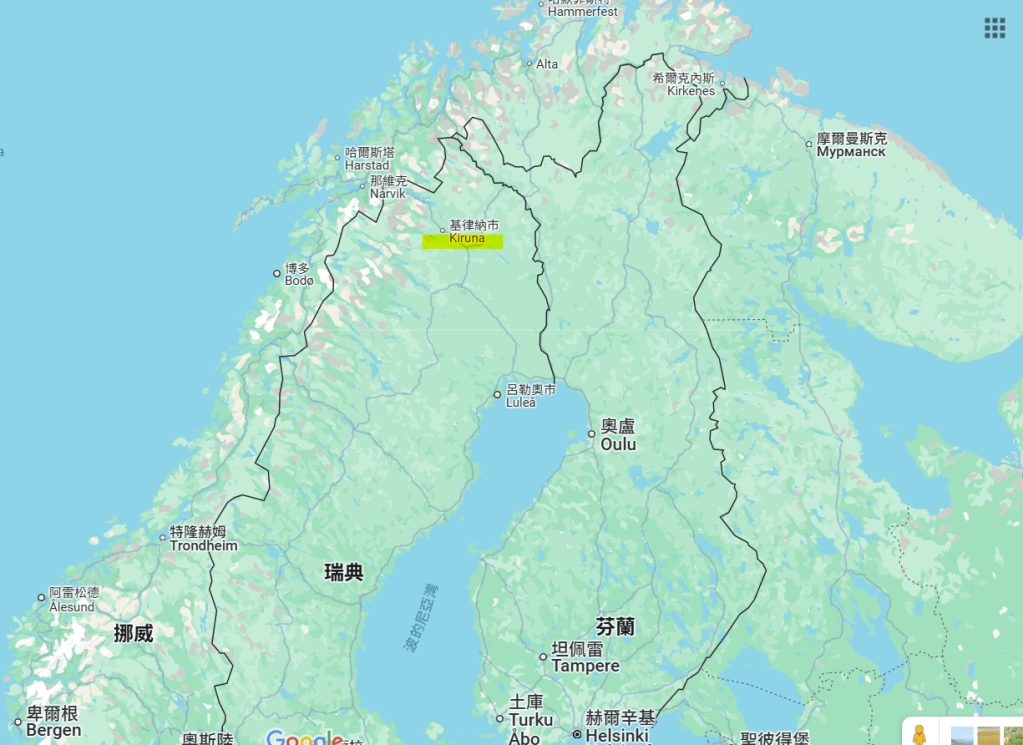

Julia: That’s an excellent question. Geology plays a huge role in shaping a country’s economy and policies. Sweden, for instance, has rich iron ore deposits, particularly in Kiruna, which powered its industrial revolution. Norway, on the other hand, struck gold—or rather, oil—with its offshore reserves in the North Sea. Finland doesn’t have comparable reserves, but it isn’t lacking either.

Emma: Really? I’ve often heard that Finland is less resource-rich compared to Sweden or Norway.

Julia: It’s true in some ways. Finland doesn’t have the massive iron ore mines like Sweden or the oil and gas fields of Norway. However, Finland is rich in other minerals like nickel, chromium, and gold. In fact, Finland is one of Europe’s top producers of nickel. These resources have been critical for modern industries like green energy and batteries.

Emma: That makes sense, especially with the shift toward sustainability. But historically, did Finland’s lack of massive mineral deposits hinder its development?

Julia: Not exactly. While Finland didn’t industrialize as quickly as Sweden, it relied heavily on its forests. Timber and paper production became the backbone of its economy, especially in the 20th century. Forestry was Finland’s “gold mine,” and even today, it remains a major industry, albeit more focused on sustainability.

Emma: And what about the people? Did these natural differences shape how society developed in these countries?

Julia: Absolutely. Sweden’s wealth from iron allowed it to industrialize early, leading to urbanization and a strong welfare state. Norway’s oil wealth, discovered in the 1960s, funded one of the most generous social systems in the world. Finland, with its more modest resources, had to rely on innovation and education to build its economy. That’s why today Finland is known for its world-class education system and technological advancements.

Emma: So, Finland turned necessity into opportunity?

Julia: Exactly. The government heavily invested in education and R&D, which helped transform Finland from an agrarian economy into a tech-driven one. Nokia’s rise in the 1990s is a great example of this shift. And let’s not forget Finland’s commitment to social equity—it has one of the most equitable societies in the world despite its late industrialization.

Emma: What about culturally? Did these geological differences affect how people see themselves?

Julia: Definitely. In Sweden, there’s a strong industrial pride, especially in regions like Kiruna. Norway, with its oil wealth, has a mix of coastal resilience and newfound economic power. Finland, however, has a more humble and resourceful identity. Its culture often emphasizes simplicity, resilience, and living in harmony with nature.

Emma: That’s fascinating. So geology doesn’t just shape landscapes—it shapes societies.

Julia: Precisely. And in the Nordic context, it’s remarkable how each country has adapted its policies and cultures to maximize its unique strengths. Even with limited mineral resources, Finland has become a global leader in sustainability and innovation.

地質塑造的國家:斯堪的納維亞的經濟、文化與社會

Emma 和 Julia 坐在奧拉維城堡的塔樓上,俯瞰塞馬湖的壯麗景色。他們的對話從芬蘭的礦產資源延伸到斯堪的納維亞三國的地質特徵,以及這些特徵如何塑造了各自的經濟、文化和社會政策。

Emma:坐在這裡,看著芬蘭廣袤的森林和湖泊,我忍不住想問——芬蘭是怎麼利用這些資源來和鄰國瑞典、挪威競爭的呢?

Julia:這是個很好的問題。地質特徵對一個國家的經濟和政策有很大的影響。瑞典有豐富的鐵礦,特別是在基律納(Kiruna),這為它的工業革命提供了動力。而挪威則靠北海的石油和天然氣成為能源大國。芬蘭雖然沒有這麼豐富的礦藏,但它也有自己的資源優勢。

Emma:真的嗎?我經常聽說芬蘭的資源不如瑞典或挪威那麼豐富。

Julia:某種程度上說是這樣。芬蘭沒有像瑞典那樣的大型鐵礦,也沒有像挪威那樣的海上石油和天然氣田。但芬蘭的鎳、鉻和金礦卻非常重要。事實上,芬蘭是歐洲最大的鎳生產國之一,這對於綠色能源和電池產業非常關鍵。

Emma:這聽起來很符合當下的可持續發展趨勢。不過,歷史上芬蘭礦藏的限制是否影響了它的發展?

Julia:不完全是。雖然芬蘭的工業化不像瑞典那麼早,但它依靠森林發展經濟。木材和造紙業在 20 世紀成為經濟支柱,森林可以說是芬蘭的「金礦」。即使到今天,這仍然是一個重要的行業,只是更加注重可持續性了。

Emma:那麼這些資源差異對芬蘭人的生活和社會結構有什麼影響嗎?

Julia:當然有。瑞典的鐵礦帶來了早期工業化,城市化進程很快,福利國家也得以早日建立。而挪威在 1960 年代發現石油後,利用能源收入建立了世界上最慷慨的社會體系之一。芬蘭雖然資源有限,但它通過創新和教育彌補了不足。今天,芬蘭以世界一流的教育和技術進步而聞名。

Emma:所以芬蘭是把挑戰變成了機會?

Julia:沒錯。政府大力投資於教育和研發,幫助芬蘭從一個農業國轉型為一個科技驅動的經濟體。諾基亞的崛起就是這種轉型的最佳例子。而且,芬蘭對社會平等的承諾使它成為世界上最平等的國家之一,即使工業化起步較晚。

Emma:那在文化上呢?這些地質差異是否影響了人們的文化認同?

Julia:當然。瑞典有很強的工業自豪感,特別是在像基律納這樣的地方。挪威則因石油財富而融合了沿海的堅韌精神和經濟優勢。而芬蘭的文化更強調謙遜和資源的有效利用。比如他們對自然的尊重和「簡樸生活」的理念,都是地質資源相對有限所塑造的文化特質。

Emma:真有趣。地質構造不僅塑造了自然景觀,也塑造了整個社會。

Julia:沒錯。在北歐的背景下,更令人欽佩的是每個國家如何根據自己的地質特徵制定政策,發揮優勢。即使像芬蘭這樣資源有限的國家,也通過可持續性和創新成為了全球的領導者。

Crossing Borders: Nordic Mobility in Work, Study, and Culture

Emma and Julia sit at a café outside Olavinlinna Castle, with sunlight filtering through the birch trees onto their table. They discuss the movement of Finnish people between neighboring countries Sweden and Norway, extending their conversation to topics of cross-border work and education.

Emma: Living here in Finland, so close to Sweden and Norway, I imagine people move between these countries quite often for work or study. Is that true?

Julia: Absolutely. Scandinavia and the Nordic countries in general have a long tradition of openness and cooperation. For instance, there’s the Nordic Passport Union, which allows citizens of Nordic countries to move freely across borders without needing a visa or residence permit.

Emma: That sounds convenient. So, do many Finns work in Sweden or Norway?

Julia: Yes, especially in Sweden. After World War II, there was significant migration from Finland to Sweden. Between the 1950s and 1970s, hundreds of thousands of Finns moved to Sweden to work in industries like manufacturing and construction. At that time, Sweden’s economy was booming, and there were labor shortages.

Emma: So, it was mostly economic migration?

Julia: Initially, yes. But it wasn’t just about jobs. Many Finns also sought a better quality of life, as Sweden offered higher wages and better social welfare programs. Over time, Finnish communities in Sweden grew, and today, Swedish cities like Stockholm and Gothenburg still have large Finnish-speaking populations.

Emma: What about Norway? Do Finns move there as well?

Julia: To a lesser extent. Norway’s oil boom in the 1960s and 1970s attracted workers from across the Nordic region, including Finland. However, Norway’s smaller population and stricter immigration policies made it less of a destination compared to Sweden.

Emma: And what about education? Do Finnish students study abroad often?

Julia: Education is another big reason for Nordic cross-border movement. Programs like Nordplus encourage students and researchers to study in other Nordic countries. Sweden and Denmark, in particular, are popular destinations for Finnish students because of their prestigious universities and proximity.

Emma: How does that affect Finland? Do these students usually return?

Julia: That’s a complex question. Many do return, bringing valuable international experience back to Finland. However, some choose to stay abroad, particularly in Sweden, where career opportunities might be more abundant. This can sometimes create a “brain drain," but Finland’s strong emphasis on education and innovation helps offset this.

Emma: I imagine the cultural exchange must be significant. How do Finns and their Nordic neighbors influence each other?

Julia: Very much so. The Nordic countries share many cultural and social values, like gender equality and environmental sustainability. But each country also brings unique perspectives. For example, Finns are often seen as more reserved compared to Swedes, but also more straightforward. These cultural interactions help strengthen the Nordic identity.

Emma: It’s fascinating how geography and shared history create such a dynamic region. Do you think this kind of mobility will increase in the future?

Julia: Likely, yes. With the EU’s broader mobility policies and the increasing importance of globalized education and work, Nordic countries will remain interconnected. And Finland, with its strong education system and growing tech sector, is becoming a destination in its own right.

跨越國界:北歐地區的工作、教育與文化流動

Emma 和 Julia 坐在奧拉維城堡外的一家咖啡館,陽光透過樺樹灑在桌上。他們討論到芬蘭人民與鄰國瑞典、挪威之間的流動,並延伸到跨國工作和教育的議題。

Emma:生活在芬蘭這裡,離瑞典和挪威這麼近,我想人們應該經常為了工作或讀書在這些國家之間流動,對嗎?

Julia:確實如此。整個斯堪的納維亞和北歐國家一向重視開放與合作。比如,北歐護照聯盟(Nordic Passport Union),允許北歐國家的公民在這些國家之間自由移動,不需要簽證或居留許可。

Emma:聽起來很方便。所以很多芬蘭人會到瑞典或挪威工作嗎?

Julia:是的,尤其是瑞典。在二戰後,很多芬蘭人移居瑞典。從 1950 年代到 1970 年代,數十萬芬蘭人移居到瑞典,主要從事製造業和建築業的工作。當時瑞典經濟蓬勃發展,但勞動力不足。

Emma:所以這主要是經濟移民?

Julia:最初是這樣的。但不只是為了工作,很多芬蘭人也希望獲得更好的生活品質,因為瑞典的工資更高,社會福利也更完善。隨著時間推移,瑞典的芬蘭人社區越來越大,今天在像斯德哥爾摩和哥德堡這些城市,仍然有大量講芬蘭語的人口。

Emma:那挪威呢?芬蘭人也會去挪威嗎?

Julia:有,但相對少一些。挪威在 1960 和 1970 年代石油繁榮時,也吸引了來自北歐其他地區的工人,包括芬蘭。但挪威人口較少,而且移民政策比瑞典更嚴格,因此吸引力稍弱。

Emma:那在教育方面呢?芬蘭學生會經常去其他國家留學嗎?

Julia:教育也是北歐跨境流動的重要原因之一。像 Nordplus 這樣的項目鼓勵學生和研究人員到其他北歐國家學習。瑞典和丹麥特別受芬蘭學生歡迎,因為它們有著聲譽卓著的大學,距離又很近。

Emma:這對芬蘭有什麼影響?這些學生通常會回來嗎?

Julia:這是個很複雜的問題。很多人會回來,將寶貴的國際經驗帶回芬蘭。但也有一些人選擇留在國外,特別是在瑞典,因為那裡的職業機會更多。這有時會造成「人才外流」,但芬蘭對教育和創新的重視在一定程度上彌補了這一點。

Emma:我想這種文化交流一定很有意義。芬蘭人和北歐鄰國之間如何互相影響呢?

Julia:影響很深。北歐國家有許多共同的文化和社會價值,比如性別平等和環境可持續性。但每個國家也有自己的特色。比如,芬蘭人通常被認為比瑞典人更內向,但也更加直率。這些文化交流加強了北歐的身份認同感。

Emma:地理和共同的歷史確實創造了一個充滿活力的區域。你認為這種人口流動未來會增加嗎?

Julia:很可能會。隨著歐盟更廣泛的流動政策,以及全球化教育和工作的需求,北歐國家之間的聯繫會更加緊密。而芬蘭憑藉其強大的教育體系和不斷增長的科技產業,也正逐漸成為一個吸引人才的目的地。

Rooted Abroad: Maintaining Language and Culture While Living in Another Country

Emma: When Finns move to Sweden or Norway, do they maintain their Finnish language and traditions, or do they assimilate into the local culture?

Julia: That depends on the context. Historically, many Finns who moved to Sweden during the mid-20th century for work tried to hold onto their language and culture, but it wasn’t easy. At that time, assimilation was often encouraged, and Finnish wasn’t widely recognized in Sweden.

Emma: So, they were expected to speak Swedish?

Julia: Exactly. Many Finnish immigrants felt pressure to adopt Swedish to fit in socially and professionally. This was especially true for children, who often attended Swedish schools and eventually became more comfortable in Swedish than Finnish.

Emma: Does that mean Finnish traditions started to fade over time?

Julia: In some cases, yes. For instance, second-generation Finnish-Swedes may have limited fluency in Finnish, although many still celebrate Finnish holidays like Vappu or Juhannus. In recent decades, though, there’s been a stronger effort to preserve Finnish identity in Sweden, especially since Finnish was officially recognized as a minority language there.

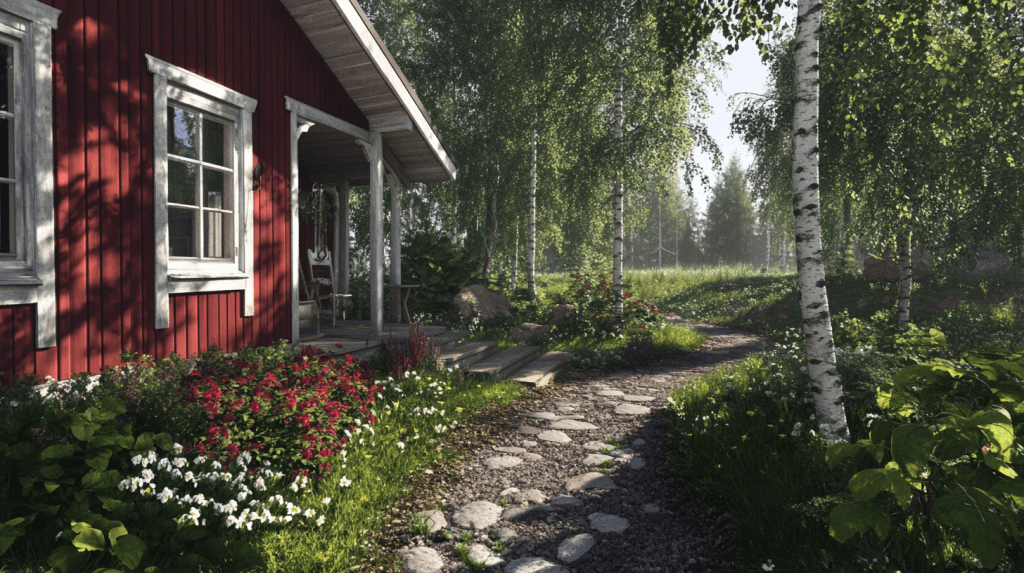

Traditional Juhannus celebration by a Finnish lake

Emma: That’s good to hear. What about the nature of migration itself? Are these moves usually permanent, or do people tend to return to Finland?

Julia: It varies. In the mid-20th century, much of the migration was permanent. Finns moved to Sweden to escape economic hardships and build new lives. Today, migration is often more temporary—students studying abroad, workers taking short-term jobs, or families relocating for a few years.

Emma: Does temporary migration make it easier to maintain one’s native language and traditions?

Julia: Definitely. Temporary migrants often see themselves as “ambassadors" of their culture, consciously preserving their language and traditions to pass on to the next generation. They may also stay connected to Finland through online communities or frequent visits home.

Emma: What about migration to Norway? Is the situation similar?

Julia: Similar, but Norway’s smaller Finnish community means there’s less institutional support for preserving Finnish culture. Still, many Finns in Norway maintain strong cultural ties, especially through organizations and events celebrating Finnish music, food, and holidays.

Emma: It sounds like preserving one’s heritage abroad takes a lot of effort.

Julia: It does, but for many migrants, it’s essential. Language and traditions are powerful ways to stay connected to one’s roots, even when living far from home. That said, the degree of preservation often depends on individual families and how strongly they value their heritage.

Emma: Do you think globalization is making it easier or harder for migrants to hold onto their traditions?

Julia: Easier in some ways. Technology allows people to stay connected to their home countries through virtual communities and cultural media. At the same time, globalization also increases pressure to adapt to dominant cultures, especially in professional and educational settings.

他鄉中的根:移居他國如何保留語言與文化

Emma:當芬蘭人搬到瑞典或挪威時,他們會保留自己的語言和傳統,還是會融入當地文化呢?

Julia:這取決於情況。歷史上,很多在 20 世紀中期搬到瑞典的芬蘭人努力保留自己的語言和文化,但這並不容易。當時,融入當地社會往往被鼓勵,芬蘭語在瑞典並沒有得到廣泛承認。

Emma:所以他們被期待說瑞典語?

Julia:沒錯。許多芬蘭移民感受到壓力,需要學瑞典語來適應社會和職場環境。這對孩子們尤其如此,他們通常上瑞典語學校,久而久之,對瑞典語的熟悉程度超過了芬蘭語。

Emma:那這是否意味著芬蘭的傳統會隨著時間而消失?

Julia:在某些情況下是這樣。例如,很多在瑞典長大的第二代芬蘭人可能只會有限的芬蘭語。不過,他們仍然慶祝像瓦普節(Vappu)或仲夏節(Juhannus)這樣的傳統節日。近幾十年來,瑞典對於保護芬蘭身份的努力加強了,特別是自從芬蘭語被正式認定為瑞典的少數民族語言以來。

慶祝瓦普節(Vappu)

Emma:聽起來不錯。那遷移的性質呢?這些移居通常是永久的,還是人們會回到芬蘭?

Julia:這因情況而異。在 20 世紀中期,大多數遷移是永久性的。芬蘭人移居瑞典是為了逃避經濟困境,尋找新生活。如今,遷移更常是暫時性的,比如學生出國留學、短期工作者,或者家庭搬遷幾年。

Emma:暫時性的移居是否更容易保留自己的語言和傳統?

Julia:確實是。暫時性的移民通常把自己視為文化的「大使」,有意識地保護自己的語言和傳統,並傳給下一代。他們還可以通過網絡社區或頻繁的返鄉保持與芬蘭的聯繫。

Emma:那移居挪威呢?情況是否相似?

Julia:有些相似,但挪威的芬蘭人社區較小,對於保留芬蘭文化的機構支持也相對較少。不過,許多在挪威的芬蘭人依然透過文化組織和活動來維繫與家鄉的聯繫,比如舉辦音樂節、傳統美食活動和慶祝芬蘭節日。

Emma:聽起來,在國外保留自己的文化需要很大的努力。

Julia:是的,但對於許多移民來說,這非常重要。語言和傳統是與故鄉保持聯繫的強大方式,即使遠離家鄉。當然,具體情況取決於每個家庭是否重視自己的文化遺產。

Emma:你認為全球化是讓移民更容易還是更難保留自己的傳統?

Julia:兩者都有。技術使人們可以透過虛擬社區和文化媒體與家鄉保持聯繫。但同時,全球化也加劇了融入主流文化的壓力,尤其是在職場和教育環境中。

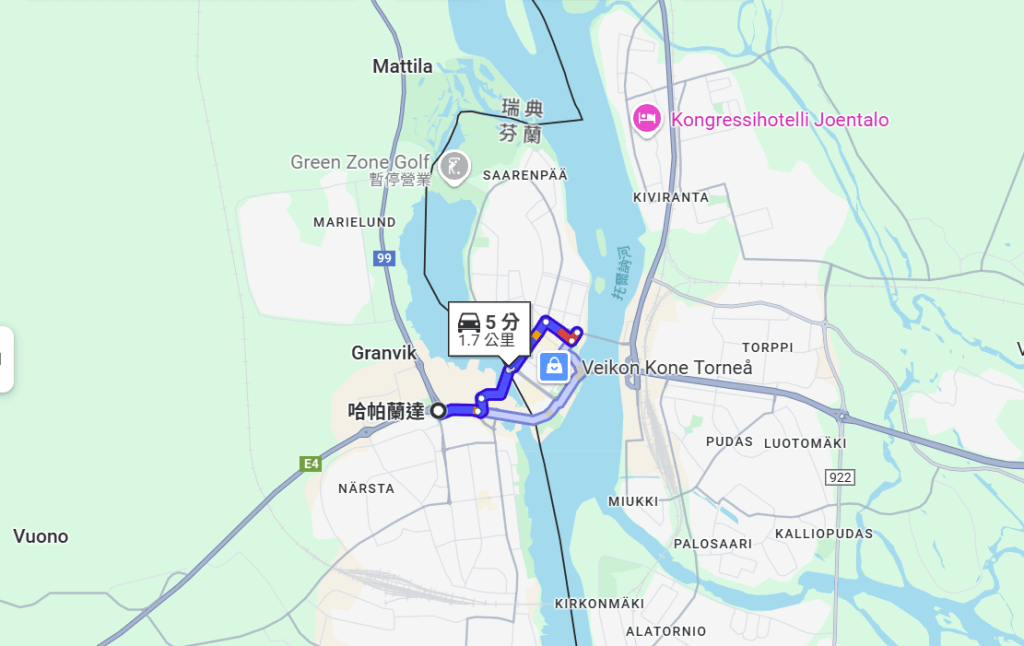

Life on the Border: Daily Crossings Between Finland and Its Neighbors

Emma: Living near the border between Finland and Sweden, do people often cross the border daily for work?

Julia: Yes, especially in towns like Tornio in Finland and Haparanda in Sweden. The border between these towns is so seamless that many residents commute daily for work, shopping, or even just leisure.

Emma: That’s fascinating. It must be convenient to have such open borders.

Julia: It is. The Nordic Passport Union allows citizens to move freely between Nordic countries, and the Schengen Agreement further removes border controls. In Tornio and Haparanda, it’s common to see people living in one country and working in the other. Some families even have homes that straddle the border!

Emma: What about the time difference? Don’t Finland and Sweden have different time zones?

Julia: They do! Finland is an hour ahead of Sweden, which can create amusing situations. For example, someone could leave work in Sweden at 5 PM and arrive home in Finland at 6 PM, or vice versa. But locals are used to it and plan their schedules accordingly.

Emma: That’s interesting. What about Norway? Do people commute across the Finland-Norway border as well?

Julia: It’s less common due to the geography. The Finland-Norway border is more remote, with fewer urban centers, but in the north, there are Sami communities that span both countries. People might cross for seasonal work, particularly in tourism or reindeer herding.

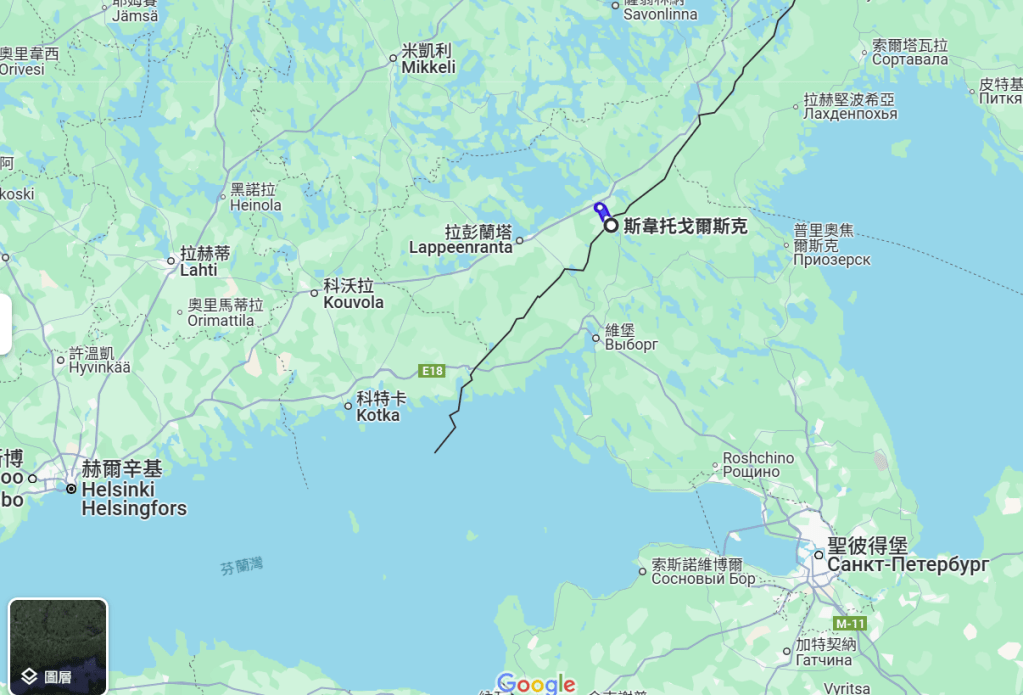

Emma: And what about Russia? Is there much cross-border commuting there?

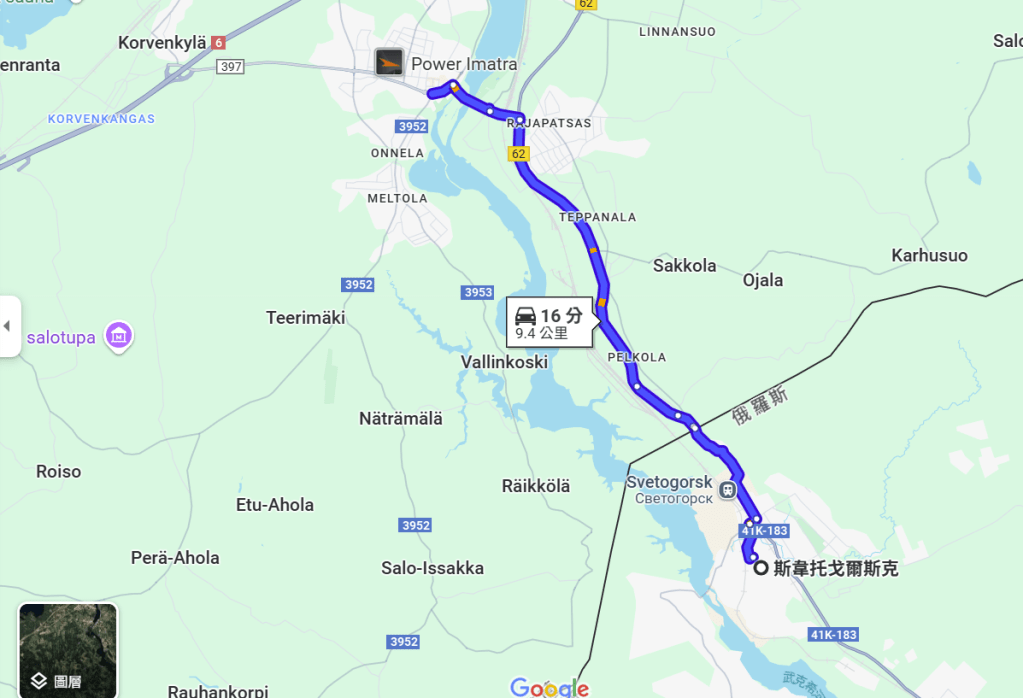

Julia: That’s a bit more complicated. The Finland-Russia border is heavily monitored, and while there is trade and some cross-border work, daily commuting is rare. However, towns like Imatra and Svetogorsk do have connections, with workers crossing for specific industries, like paper production.

Emma: So, what kind of work do people typically do when commuting across these borders?

Julia: It depends on the region. In Tornio and Haparanda, retail and logistics are big industries. For example, many Finns work in Swedish shops because of higher wages, while Swedes often come to Finland for more affordable housing. In the north, reindeer herding and tourism are significant. On the Russian side, it’s more about industrial jobs like paper mills or border trade.

Emma: How does this affect the local economies?

Julia: Border regions tend to have more integrated economies. For example, Finnish businesses in Tornio benefit from Swedish customers, and vice versa. However, disparities in wages or taxes can create tension. For instance, Swedes might shop in Finland to avoid higher VAT, which can frustrate local Swedish businesses.

Emma: And socially? Does this cross-border movement strengthen ties between these countries?

Julia: Definitely. In the Nordic countries, border communities often see themselves as part of a shared region rather than separate nations. Festivals, schools, and even healthcare can be shared across borders. However, language differences sometimes pose a challenge.

Emma: It sounds like a fascinating dynamic. Are there any downsides?

Julia: Occasionally. Border areas can experience uneven economic development, and reliance on cross-border work can make communities vulnerable to political changes, like stricter border controls during the pandemic. But overall, these regions are great examples of how borders can unite rather than divide.

邊界生活:芬蘭與鄰國之間的日常往返

Emma 和 Julia 坐在薩翁林納的一家餐廳靠窗的位置,討論居住在芬蘭邊界的人們如何跨境往返瑞典、挪威,甚至俄羅斯工作。

Emma:住在芬蘭和瑞典邊界附近的人,會經常每天跨境去工作嗎?

Julia:會的,特別是在芬蘭的托爾尼奧(Tornio)和瑞典的哈帕蘭達(Haparanda)這樣的城鎮。這兩個城鎮的邊界幾乎是無縫的,很多居民每天都會跨境通勤工作、購物,甚至只是休閒活動。

Emma:真有趣。這樣開放的邊界一定很方便吧?

Julia:是的。北歐護照聯盟允許公民在北歐國家之間自由移動,而申根協議進一步取消了邊境管控。在托爾尼奧和哈帕蘭達,很多人住在一個國家,工作在另一個國家。有些家庭甚至住在跨越邊界的房子裡!

Emma:那時區不同會不會造成麻煩?芬蘭和瑞典的時區應該不一樣吧?

Julia:沒錯!芬蘭比瑞典早一個小時,這會帶來一些有趣的情況。比如,有人可能在瑞典下午五點下班,到芬蘭時就已經是六點了。當地人早就習慣了,會根據這個調整自己的時間安排。

Emma:好有趣啊!那芬蘭和挪威之間呢?人們也會跨境通勤嗎?

Julia:相對較少,因為芬蘭和挪威的邊界比較偏遠,城市中心不多。但在北部地區,有薩米人社區分布在兩國邊界。他們可能會因為季節性的工作,比如旅遊業或馴鹿放牧而跨境活動。

Emma:那與俄羅斯呢?那邊會有跨境通勤嗎?

Julia:情況就比較複雜了。芬蘭和俄羅斯的邊界管控很嚴格,雖然有貿易和部分跨境工作,但每天通勤的情況比較少。不過像伊馬特拉(Imatra)和斯維托戈爾斯克(Svetogorsk)這樣的城鎮之間,的確有一些工人跨境往返,比如造紙業的工廠。

Emma:那這些跨境工作者通常從事什麼樣的工作呢?

Julia:這取決於地區。在托爾尼奧和哈帕蘭達,零售和物流業很大。比如,很多芬蘭人在瑞典的商店工作,因為工資更高,而瑞典人則會來芬蘭購買更便宜的房子。在北部地區,馴鹿放牧和旅遊業是重要行業。在俄羅斯邊界,更多的是工業工作,比如造紙廠或邊境貿易。

Emma:這對當地經濟有什麼影響?

Julia:邊界地區的經濟通常更緊密地聯繫在一起。比如,托爾尼奧的芬蘭商家會受益於瑞典顧客,反之亦然。但薪資或稅收的差異有時會引發矛盾。比如,瑞典人可能會到芬蘭購物以避開更高的增值稅,這可能讓瑞典的本地商家感到不滿。

Emma:那在社會層面呢?這種跨境活動是否會加強國家之間的聯繫?

Julia:確實會。在北歐,邊界社區往往認為自己屬於一個共同的區域,而不是單純的國家分界。比如,有些節日、學校,甚至醫療服務都是跨境共享的。不過,語言差異有時會構成挑戰。

Emma:聽起來真有趣。那這樣的邊界生活有沒有什麼缺點呢?

Julia:偶爾會有。邊界地區可能會出現經濟發展不平衡,而依賴跨境工作也會讓這些社區容易受到政治變動的影響,比如疫情期間更嚴格的邊境管控。但總體來說,這些地區是邊界如何連接而不是分隔的絕佳例子。

發表留言