A Scholarly Dialogue at the University of Belgrade

The scene takes place in a quiet lounge inside the University of Belgrade during a coffee break. The room has high ceilings, classical columns, and a large window overlooking the campus courtyard.

Emma: You know, sitting here, surrounded by all this history, makes me realize how deeply education is tied to the shaping of nations.

Julia: It’s true. The University of Belgrade, established in 1808, is a perfect example. It began as a small college during Serbia’s struggle for independence. At the time, education wasn’t just about learning—it was an act of resistance.

Emma: Resistance against the Ottoman Empire, right? Serbia was still under Ottoman rule then.

Julia: Exactly. The university symbolized a cultural awakening, a way to preserve Serbian identity while preparing for autonomy. It attracted intellectuals who became leaders of the independence movement.

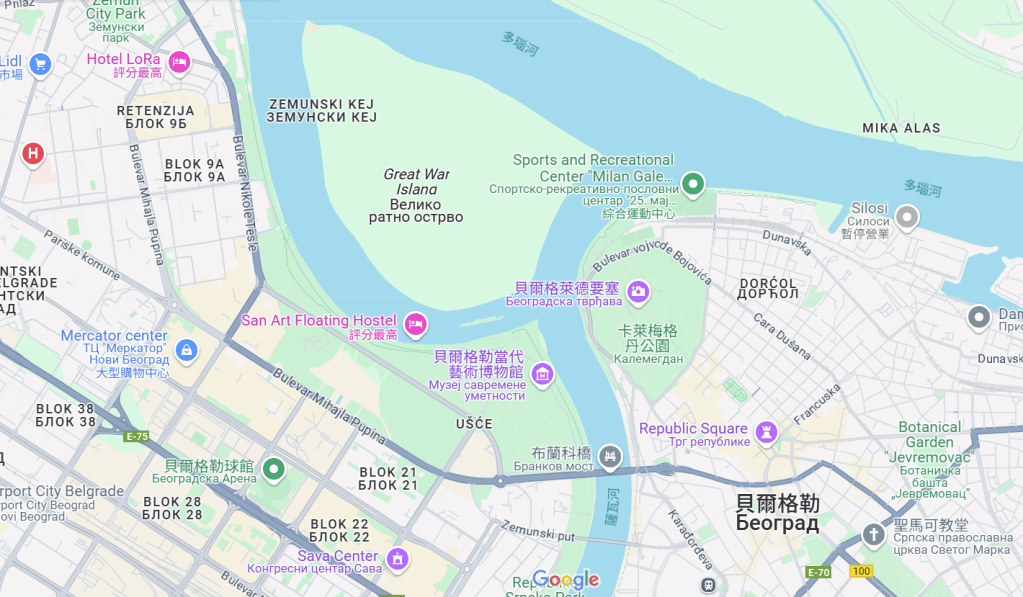

Emma: It’s incredible how education and politics intertwined so closely. And Belgrade itself—it’s such a strategic location. No wonder this city has been the site of so many conflicts.

Julia: Yes, its position at the confluence of the Danube and Sava Rivers made it invaluable for trade, defense, and expansion. That’s why it’s been destroyed and rebuilt so many times—more than 40, if I remember correctly.

Emma: I read that even the Romans valued this spot. They called it Singidunum. The layers of history here must be fascinating to archaeologists.

Julia: They are. You can see Roman ruins scattered across the city, but the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian influences are just as prominent. It’s like the city carries the weight of every empire that passed through.

Emma: Do you think the conference organizers chose this location deliberately, considering its layered history?

Julia: Absolutely. Belgrade isn’t just geographically at the crossroads of Europe—it’s intellectually and politically significant, too. This university is a testament to how education can rebuild and transform societies.

Emma: After the sessions today, we should visit Kalemegdan Fortress. It’s the perfect place to reflect on how this city has endured through centuries of conflict and change.

Julia: Agreed. And perhaps we can discuss how these historical patterns of resilience relate to the topics we’re covering in the conference. The Balkans are a microcosm of global geopolitics.

貝爾格勒大學的學者對話

場景設定在貝爾格勒大學內的一個安靜休息室,咖啡休息時間。高高的天花板、古典的柱子和大窗戶俯瞰著校園庭院,氣氛靜謐而莊嚴。

Emma:坐在這裡,被這些厚重的歷史包圍,讓我更加體會到教育是如何深刻地與國家的形成緊密聯繫在一起。

Julia:是的。貝爾格勒大學就是一個典型的例子。它創建於1808年,那時正值塞爾維亞的獨立鬥爭時期。那時候,教育不僅僅是學習,還是一種抵抗的行動。

Emma:是對奧斯曼帝國的抵抗吧?當時塞爾維亞還在奧斯曼統治之下。

Julia:沒錯。這所大學成為一種文化覺醒的象徵,是保留塞爾維亞身份的重要手段,同時也為自治做準備。許多知識分子聚集於此,後來成為了獨立運動的領導者。

Emma:教育與政治如此緊密相連,真的令人驚嘆。而且貝爾格勒本身的地理位置也太重要了,難怪這裡成為了衝突的熱點。

Julia:是的,它位於多瑙河和薩瓦河的交匯處,是貿易、防禦和擴張的寶地。這也是為什麼這座城市被摧毀又重建超過40次,如果我沒記錯的話。

Emma:我還讀到羅馬人也非常看重這個地方,當時叫它Singidunum。這裡的歷史層次對考古學家來說一定很有吸引力。

Julia:確實如此。你可以在城市的各處看到羅馬遺跡,但奧斯曼和奧匈帝國的影響也同樣明顯。這座城市彷彿承載了每一個經過的帝國的重量。

Emma:你覺得會議的主辦方選擇這個地點,是不是也有意突顯它的歷史意義?

Julia:毫無疑問。貝爾格勒不僅在地理上是歐洲的交匯點,在知識和政治上也有重要的地位。這所大學正好體現了教育如何重建和改變社會。

Emma:今天的會議結束後,我們應該去卡萊梅格丹城堡走走。在那裡可以更好地思考這座城市如何在數百年的衝突與變遷中生存下來。

Julia:好啊。我們還可以討論這些歷史模式的韌性,看看它們如何與我們在會議中討論的巴爾幹地區的地緣政治問題相呼應。

Walking from the University of Belgrade to Kalemegdan Fortress

Emma and Julia step out of the University of Belgrade, walking along the stone-paved streets toward Kalemegdan Fortress. The city around them is a blend of neoclassical, Ottoman, and modernist architecture, a reflection of Belgrade’s layered past. The afternoon sun casts a soft golden hue over the buildings as they discuss history.

Emma: It’s fascinating how this city reflects so many different layers of history. Walking through Belgrade, you can literally see the remnants of the empires that once ruled here—Ottoman mosques, Austro-Hungarian facades, and Socialist-era buildings all standing side by side.

Julia: That’s what makes Belgrade so unique. Unlike other European capitals that have carefully preserved their historic cores, this city has been destroyed and rebuilt so many times that it’s become a palimpsest of its own past.

Emma: And yet, it still holds onto its identity. Even after being caught between empires, wars, and political upheavals, it remains unmistakably Serbian.

Julia: Exactly. That’s why it was chosen as the capital of Yugoslavia after World War I—it was a natural meeting point for the South Slavic peoples. But if you think about it, even Yugoslavia itself was an attempt to unify historically divided regions under one identity.

Emma: A difficult task, given the deep-rooted divisions in the Balkans.

Julia: And that’s precisely why Belgrade was so important. It wasn’t just the political center—it was the ideological heart of Yugoslavia, where ideas of unity and division constantly clashed.

They approach Kalemegdan Park, where the fortress stands high above the confluence of the Danube and Sava Rivers. The vast park surrounding the fortress is filled with trees just beginning to bud, signaling the transition from winter to spring.

At Kalemegdan Fortress, Overlooking the Danube and Sava

The two scholars walk up the stone steps of Kalemegdan Fortress. Standing at the edge of the ancient walls, they gaze out at the rivers below, where the waters of the Danube and Sava merge. A cool breeze carries the scent of damp earth and fresh foliage, a reminder of the changing seasons.

Emma: Standing here, it’s easy to see why every empire wanted this place. Controlling this fortress meant controlling the entire region.

Julia: Exactly. The Romans built the first fortifications here over two thousand years ago. They understood the significance of this confluence—it was not just a military stronghold but also a crucial trade route.

Emma: And then came the Byzantines, followed by the medieval Serbian rulers. It’s almost poetic how history keeps repeating itself in the Balkans.

Julia: And then the Ottomans arrived. In 1521, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent captured Belgrade, making it one of the key cities in the Ottoman Empire. It remained under their rule for nearly three centuries.

Emma: But it wasn’t a peaceful occupation, was it?

Julia: Far from it. The Habsburgs repeatedly tried to take it back. They captured it several times but never held onto it for long. The fortress became a symbol of the struggle between the Christian and Muslim worlds in Europe.

Emma: And this back-and-forth didn’t really end until the 19th century, when Serbia finally regained control.

Julia: Yes, in 1867. That was when the last Ottoman governor ceremoniously handed over the keys to the city. It marked Serbia’s full independence, though true stability was still a long way off.

Emma looks down at the rivers, deep in thought. The Danube stretches far beyond the horizon, connecting Belgrade to Budapest, Vienna, and beyond.

Emma: The Danube was both a barrier and a bridge. It separated empires, but it also connected them.

Julia: That’s why this region has always been a geopolitical flashpoint. The Balkans weren’t just a buffer zone between East and West—they were the very battleground where those worlds collided.

Emma: And they still are. The wars may have changed, but the struggle over influence in this region continues.

Julia: Indeed. Even today, Serbia finds itself caught between East and West, balancing its historical ties to Russia with its aspirations to join the European Union. The echoes of history never really fade, do they?

Emma: No, they don’t. But standing here, with the city stretching out before us, I can’t help but feel that despite all the conflicts, Belgrade has survived.

Julia: It always does. This city, this fortress—it has endured everything history has thrown at it. That resilience is part of its identity.

They stand in silence for a moment, the wind carrying the scent of damp stone and river water. The sun begins to set, casting long shadows across the fortress walls. Below them, the rivers continue to flow, just as they have for millennia.

從貝爾格勒大學步行至卡萊梅格丹城堡

Emma 和 Julia 結束了會議,沿著鋪滿石板的街道步行前往卡萊梅格丹城堡。貝爾格勒的街道融合了新古典風格、奧斯曼風格與現代建築,反映出這座城市的歷史層次。午後的陽光灑在建築上,柔和的光線勾勒出歷史的痕跡。

Emma:這座城市真的很特別,彷彿歷史就這樣鋪展在我們眼前。奧斯曼清真寺、奧匈帝國建築、社會主義時代的高樓並存,這種對比令人驚嘆。

Julia:這正是貝爾格勒的獨特之處。和歐洲許多精心修復的城市不同,這裡承受了無數次戰爭與破壞,每一代人都在廢墟之上重建這座城市。

她們走進卡萊梅格丹公園,前方的城堡矗立在多瑙河與薩瓦河交匯處的高地上。四周的樹木開始發芽,冬春交替的季節為古老的石牆增添了些許生氣。

卡萊梅格丹城堡上,俯瞰多瑙河與薩瓦河

Emma:站在這裡,真的能感受到這座城堡的戰略價值。誰控制了這裡,誰就掌控了整個區域。

Julia:羅馬人早在兩千年前就築起了第一道防禦工事,他們明白這個交匯點的重要性。

Emma:然後是拜占庭人、塞爾維亞王國、奧斯曼人……歷史總是在巴爾幹重演。

Julia:確實如此,這裡曾是東西方勢力的戰場,至今仍然如此。歷史的回聲仍然在這片土地上迴盪。

The Crossroads of Empires: How Belgrade’s Strategic Position Shaped History

Discussing the Impact at Kalemegdan Fortress

Emma and Julia stand by the ancient stone walls of Kalemegdan Fortress, overlooking the confluence of the Danube and Sava Rivers. The afternoon sun casts a golden glow over the water, while a crisp spring breeze rustles the budding branches nearby.

Geopolitical Impact

Julia: This place has always been a battleground for power. Controlling this fortress meant controlling the key passage between Central Europe and the Balkans.

Emma: That’s why Belgrade has been destroyed and rebuilt over forty times. Every major power that came through here—Romans, Byzantines, Ottomans, the Austro-Hungarians—knew that this was the key to controlling the region.

Julia: Even in modern times, its strategic position kept it at the center of conflict. During both World Wars and later in the NATO bombings of 1999, Belgrade remained a crucial target.

Economic and Trade Influence

Emma: Beyond military control, the economic importance of this city is undeniable. The Danube has been a lifeline for trade for centuries, connecting Western and Eastern Europe.

Julia: During Ottoman rule, Belgrade became a commercial hub, linking Istanbul with Central Europe. Markets flourished, and trade routes extended deep into the empire.

Emma: But that economic prosperity also made it a prize to be fought over. Every empire that ruled here sought to control its wealth and resources.

Julia: Even today, Serbia continues to rely on the Danube for trade and seeks a balance between European markets and Russian economic ties.

Cultural and Religious Impact

Emma: The cultural diversity here is remarkable. Walking through Belgrade, you see Orthodox churches, Catholic cathedrals, and remnants of Ottoman mosques—it’s a city of blended identities.

Julia: That’s because Belgrade was never just Serbian—it was Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian at different points in history. Each left its mark.

Orthodox Church

Ottoman Mosques

Emma: But that cultural richness also bred division. Religious and ethnic conflicts have shaped the Balkans for centuries. Even in Yugoslavia, the tensions never really disappeared.

Julia: Exactly. The city embodies a paradox—it has absorbed multiple influences but has also been a site of deep conflict between them.

Political and Modern Influence

Emma: And now, Serbia finds itself at another crossroads. It has historical ties to Russia but also aspires to integrate with the European Union.

Julia: That’s a continuation of its historical role. For centuries, Belgrade has been the meeting point between East and West—first between empires, now between political blocs.

Emma: It’s fascinating how history never truly ends. The wars may have changed, but the struggle for influence in this region continues.

Julia: And through it all, this fortress remains. It has seen empires rise and fall, and yet it still stands, bearing witness to history’s cycles.

帝國的十字路口:貝爾格勒的戰略地位如何塑造歷史

Julia 和 Emma 站在卡萊梅格丹城堡的石牆邊,俯瞰著多瑙河和薩瓦河的交匯處。天空清朗,春風輕拂著古老的城牆,讓人不禁思考這片土地上數千年的歷史變遷。

地緣戰略影響

Julia:這片土地的命運從來都與它的地理位置緊密相連。貝爾格勒位於巴爾幹半島的心臟地帶,控制了歐洲內陸和東南部之間的交通動脈。這不僅讓它成為軍事要塞,也成為了貿易的必經之地。

Emma:這也解釋了為什麼這座城市被摧毀和重建了 40 多次。無論是羅馬人、拜占庭人,還是奧斯曼帝國,他們都知道控制這裡意味著控制東西方之間的樞紐。

Julia:甚至到了近代,貝爾格勒仍然是軍事與政治爭奪的中心。第一次和第二次世界大戰期間,這裡仍是歐洲戰爭的前線,甚至在 1999 年北約轟炸時,它仍然是關鍵的戰略目標。

貿易與經濟影響

Emma:除了軍事,這裡也是歐洲的經濟命脈之一。多瑙河是一條貿易動脈,從德國流經中歐一直到黑海。這意味著貝爾格勒一直是商隊、貨運船隻的重要停靠點。

Julia:奧斯曼人統治期間,這裡成為連接伊斯坦堡與中歐的重要商業據點。奧斯曼帝國在這裡建設了市場、橋樑和道路,讓貝爾格勒成為貿易中心之一。

Emma:但這也是問題的一部分。每個統治者都想控制這裡的財富和資源,這導致了無數次的戰爭和掠奪。

Julia:即使到了今天,塞爾維亞仍然依賴多瑙河的貿易,並試圖在歐盟與俄羅斯之間保持經濟平衡。

文化與宗教影響

Emma:巴爾幹半島的多元文化背景在貝爾格勒表現得尤為明顯。你可以在城裡找到東正教教堂、天主教堂,甚至是奧斯曼時期留下的清真寺。

Julia:這正是因為貝爾格勒曾經是不同文明的交會點。羅馬時期,這裡是拉丁文化的一部分;拜占庭時期,它是東正教世界的一部分;奧斯曼統治下,伊斯蘭文化影響了當地的生活方式;到了奧匈帝國時代,西歐文化也滲透了進來。

Emma:但這種多元性也帶來了衝突。宗教和文化的對立讓巴爾幹地區一直處於不穩定狀態,即使在南斯拉夫時代,這種分裂仍然存在於社會的深層結構中。

Julia:這也讓貝爾格勒成為一座矛盾的城市,它既有歐洲的浪漫,又帶著東方的神秘。

政治與現代影響

Emma:南斯拉夫解體後,塞爾維亞的政治定位變得更加複雜。這個國家一直處於東西方的拉鋸戰之間。

Julia:是的,它與俄羅斯有歷史上的聯繫,但又希望融入歐洲市場。這種微妙的平衡與數百年來的歷史影響一脈相承。

Emma:這讓我想到,歷史從來沒有真正結束。貝爾格勒的故事仍在延續,它仍然是一個十字路口,只是這次的戰場從軍事變成了經濟與政治競爭。

Julia:沒錯。而這座城堡依然矗立在這裡,見證著歷史的每一次循環。

她們沉默了一會兒,望向遠方的河流。陽光透過雲層灑在水面上,彷彿將歷史的碎片映照在波光之間。

Belgrade’s Religious Legacy Under Communism

Emma and Julia stand in front of the grand Serbian Orthodox church, Saint Sava Temple. The white marble facade gleams under the afternoon sun, its large green dome adorned with golden crosses. The surrounding trees are budding, signaling the transition from winter to spring. They pause to take in the view before engaging in a historical discussion.

Was Belgrade Ever Part of the Soviet Union?

Standing Outside Saint Sava Temple, Belgrade

Emma: Standing here, I can’t help but wonder—was Serbia ever part of the Soviet Union?

Julia: No, it wasn’t. Yugoslavia, which included Serbia, was a socialist state but not a Soviet satellite. Tito, the leader of Yugoslavia, broke away from Stalin in 1948.

Emma: Right, the Tito-Stalin split. So Yugoslavia was communist but followed its own path?

Julia: Exactly. Tito pursued a policy of non-alignment, meaning Yugoslavia wasn’t fully in either the Soviet or Western bloc. It remained socialist, but with more openness to the West than other Eastern European communist states.

Emma: That must have created tension—being communist but independent from Moscow.

Julia: It did. But it also meant that Yugoslavia had a unique socialist model—workers’ self-management instead of state-controlled industries, more economic flexibility, and somewhat more cultural freedom.

The Impact of Communism on Religion

Emma: But Yugoslavia was still a communist state, and communism generally opposed religion. How did that affect churches like this one?

Julia: Well, like most communist regimes, Yugoslavia promoted atheism and sought to reduce the influence of the church. Religious institutions lost much of their power, and many clergy were persecuted, especially in the early years of Tito’s rule.

Emma: Was there direct suppression, like in the Soviet Union, where churches were destroyed or converted into secular buildings?

Julia: Not to the same extreme, but the government did nationalize church properties and restrict religious education. While churches weren’t demolished on a large scale, they were sidelined in public life.

Emma: And yet, Saint Sava Temple still stands. Was it always active during communism?

Julia: No, actually. This church is a perfect example of how communism suppressed religion. Construction on Saint Sava Temple started in the 1930s, but after the communists took power in 1945, they stopped all work on it for decades.

Emma: So it was left unfinished?

Julia: Exactly. For nearly 40 years, it stood as a skeleton of a church. Only in the late 1980s, as communism weakened, did construction resume. It became a powerful symbol of Serbia’s return to its Orthodox roots.

Religion and National Identity After Communism

Emma: That makes sense—when communism collapsed, there was a resurgence of national identity, and for Serbia, that meant reconnecting with Orthodox Christianity.

Julia: Yes. After the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, religious identity became deeply tied to national identity. The Serbian Orthodox Church regained its influence, and Saint Sava Temple was finally completed in the 2000s.

Emma: It’s interesting how religion, once suppressed, became a defining feature of the post-communist era.

Julia: That’s the paradox. Communism tried to erase religion, but in the long run, it didn’t succeed. If anything, the repression made religious identity stronger.

Emma: I guess history shows that faith and ideology are always in tension, but neither ever truly disappears.

Julia: Exactly. And here we are, standing in front of a church that survived wars, dictatorships, and communism—yet remains one of the most important symbols of Serbian identity.

They stand in silence for a moment, gazing at the grand structure before them, a testament to resilience in the face of ideological struggles.

共產主義時期貝爾格勒的宗教遺產

Emma 和 Julia 站在貝爾格勒宏偉的聖薩瓦大教堂前,白色大理石的外牆在午後陽光下閃耀,巨大的綠色圓頂上點綴著金色十字架。樹木開始發芽,標誌著冬春交替的時節。她們凝視著這座教堂,展開了一場關於歷史與宗教的對話。

A historic Ottoman-style mosque in Belgrade, Serbia

塞爾維亞曾是蘇聯的一部分嗎?

Emma:站在這裡,我不禁想到——塞爾維亞曾經是蘇聯的一部分嗎?

Julia:不,塞爾維亞屬於南斯拉夫,而南斯拉夫是社會主義國家,但並不是蘇聯的衛星國。1948 年,鐵托與史達林決裂,使得南斯拉夫走上了獨立的社會主義道路。

Emma:對,鐵托-史達林決裂。所以南斯拉夫雖然是共產主義國家,但沒有完全追隨莫斯科?

Julia:沒錯。鐵托採取不結盟政策,南斯拉夫既不完全屬於蘇聯陣營,也不完全屬於西方陣營。它保持社會主義體制,但在經濟和文化上比東歐其他共產國家開放一些。

Emma:這樣的立場一定讓局勢變得更加複雜——既是共產主義,又要獨立於蘇聯。

Julia:確實如此。但這也讓南斯拉夫有了自己的社會主義模式,例如工人民主管理,經濟比其他共產國家更具彈性,文化政策也稍微寬鬆一些。

共產主義對宗教的影響

Emma:但畢竟南斯拉夫還是共產主義國家,而共產主義通常反對宗教。這對教堂造成什麼影響?

Julia:與蘇聯類似,南斯拉夫政府提倡無神論,並試圖削弱教會的影響力。許多宗教機構被國有化,神職人員在早期受到迫害。

Emma:蘇聯時期有許多教堂被毀,甚至改建成世俗用途,南斯拉夫也發生過嗎?

Julia:情況沒有那麼極端,但教會確實被排擠。政府沒大規模拆除教堂,但限制宗教活動,宗教教育被禁止,教會失去了許多財產。

Emma:可聖薩瓦大教堂仍然矗立在這裡。它一直是活躍的宗教場所嗎?

Julia:不,這正是共產主義抑制宗教的例子之一。聖薩瓦大教堂的建設始於 1930 年代,但共產黨在 1945 年上台後,全面停止了工程,讓這座教堂荒廢了將近 40 年。

Emma:所以它被擱置了?

Julia:沒錯。直到 1980 年代末,共產主義政權開始動搖,工程才得以恢復。這座教堂成為塞爾維亞尋回東正教信仰的重要象徵。

Yugoslavia’s Complex Legacy: History and Identity

Emma and Julia sit in a cozy café near Saint Sava Temple, sipping their coffee. The café has wooden interiors, a few Orthodox icons on the walls, and a quiet ambiance. Outside, the early spring air is crisp, and the city of Belgrade bustles in the background. Their conversation turns to the complexity of Yugoslavia’s history.

The Birth of Yugoslavia

Emma: I was reading about the history of Yugoslavia before our trip, and I have to admit—it’s complicated. How did it even come into existence?

Julia: It really is complicated. The first Yugoslavia, called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, was created after World War I in 1918. It was meant to unite the South Slavic peoples who had previously been under different empires—the Austro-Hungarians in the north and the Ottomans in the south.

Emma: So the idea was to bring together different Slavic nations under one state?

Julia: Yes, but the problem was that these groups had very different histories, cultures, and even religions. The Serbs were Orthodox, the Croats were Catholic, and the Bosniaks were largely Muslim due to Ottoman influence.

Emma: That sounds like a fragile foundation for a new country.

Julia: Exactly. From the very beginning, tensions arose. The Serbs dominated politically, which made the Croats and Slovenes feel like they were being sidelined. There was no real sense of unity beyond the idea of shared Slavic identity.

World War II and the Partisan Resistance

Emma: And then World War II came along and tore everything apart.

Julia: Completely. When the Axis powers invaded in 1941, Yugoslavia collapsed almost instantly. The Germans occupied Serbia, the Italians took over parts of the Adriatic, and Croatia became a Nazi puppet state under the Ustaše.

Emma: The Ustaše… they were brutal, weren’t they?

Julia: Extremely. They carried out genocide against Serbs, Jews, and Roma. Meanwhile, different factions emerged—there were the royalist Chetniks, who wanted to restore the old monarchy, and the communist Partisans, led by Tito, who fought for a new Yugoslavia.

Emma: And Tito won in the end.

Julia: Yes. By 1945, the Partisans had driven out the Axis forces and abolished the monarchy. Tito then established the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which was very different from the first Yugoslavia.

Tito’s Yugoslavia: Unity or Illusion?

Emma: So, under Tito, Yugoslavia became communist. Was it like the Soviet Union?

Julia: Not quite. Tito broke away from Stalin in 1948, refusing to be a Soviet satellite. That’s why Yugoslavia followed a unique socialist model, with more economic openness and self-management instead of strict state control.

https://www.icty.org/en/about/what-former-yugoslavia

Emma: And yet, despite being communist, Yugoslavia was more connected to the West than other Eastern Bloc countries?

Julia: Exactly. It received aid from both the US and the USSR at different times, balancing between the two. Tito also promoted the Non-Aligned Movement, meaning Yugoslavia didn’t fully align with either superpower during the Cold War.

Emma: It sounds like Tito held everything together through sheer force of personality.

Julia: That’s not far from the truth. His leadership kept ethnic tensions in check, but those divisions never really went away. They were just suppressed.

The Breakup of Yugoslavia: Nationalism Awakens

Emma: And when Tito died in 1980, everything started falling apart?

Julia: Not immediately, but the cracks widened. The federal structure of Yugoslavia gave each republic some autonomy, but without Tito’s leadership, nationalism began to rise. Economic decline in the 1980s made things worse.

Emma: Was it inevitable that Yugoslavia would collapse?

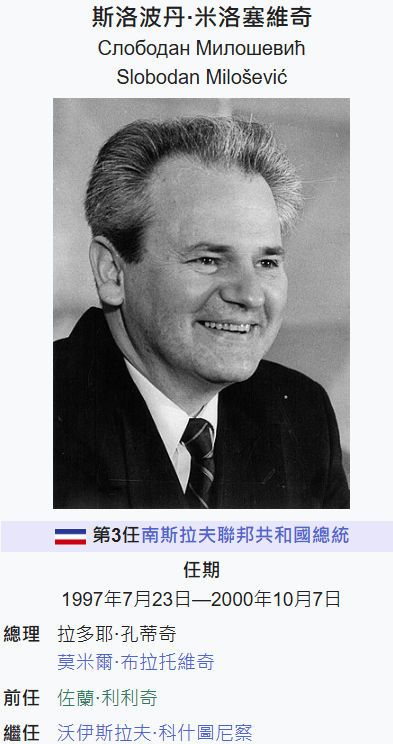

Julia: Many historians think so. By the late 1980s, leaders like Slobodan Milošević in Serbia began pushing for greater centralization, which alarmed other republics like Croatia and Slovenia.

Emma: And then the wars began.

Julia: Yes. Slovenia was the first to break away in 1991, and their war was relatively short. But Croatia and Bosnia were a different story. Those wars were brutal, with ethnic cleansing, massacres, and sieges—like the siege of Sarajevo, which lasted nearly four years.

Emma: It’s horrifying to think about how neighbors turned against each other.

Julia: That’s the tragedy of Yugoslavia. People who had lived side by side for decades suddenly found themselves on opposite sides of a war, often due to political manipulation.

The Legacy of Yugoslavia Today

Emma: And Serbia ended up as the last to let go of the Yugoslav identity?

Julia: Pretty much. After the wars, what remained of Yugoslavia became just Serbia and Montenegro. Even that dissolved in 2006 when Montenegro voted for independence. Kosovo later declared independence from Serbia in 2008, though not all countries recognize it.

Emma: So, does anyone still identify as Yugoslav today?

Julia: A small number of people still do, especially older generations who remember Tito’s Yugoslavia fondly. Some see it as a time of stability, but others remember the repression. It depends on who you ask.

Emma: And in the broader region, do people regret the breakup?

Julia: Again, it depends. Some believe that things were better under Yugoslavia, especially economically, while others see national independence as worth the cost. The wounds of the wars are still fresh in many places.

Emma: It’s incredible how one country’s story encapsulates so much of 20th-century history—colonial rule, war, communism, nationalism, and ultimately, fragmentation.

Julia: That’s why Yugoslavia remains such a fascinating and complex topic. It’s a reminder that unity imposed from above can only last as long as there’s enough force to hold it together.

They sip their coffee in silence for a moment, reflecting on the weight of history. Outside, the bells of Saint Sava Temple chime softly, a sound that has echoed through Belgrade for centuries.

南斯拉夫的複雜遺產:關於歷史與身份的對話

Emma 和 Julia 坐在貝爾格勒聖薩瓦大教堂附近的一家咖啡館裡,桌上擺著熱騰騰的咖啡。木質裝潢的咖啡館牆上掛著幾幅東正教的聖像,整個氛圍寧靜而莊重。窗外,初春的空氣清新,貝爾格勒的街道車水馬龍。他們的對話轉向南斯拉夫的複雜歷史。

南斯拉夫的誕生

Emma:在來這裡之前,我特地查了一下南斯拉夫的歷史,但實在是太複雜了。這個國家最初是怎麼誕生的?

Julia:第一次世界大戰結束後,1918 年成立了 塞爾維亞人、克羅埃西亞人和斯洛文尼亞人王國,後來改名為南斯拉夫王國。這個國家的誕生是為了將原本屬於奧斯曼帝國和奧匈帝國的南斯拉夫民族統一起來。

Emma:也就是說,這個國家是由不同的斯拉夫民族組成的?

Julia:沒錯。但問題是,這些民族的歷史和文化差異很大,甚至宗教信仰也不同。塞爾維亞人是東正教徒,克羅埃西亞人是天主教徒,而波士尼亞人則受奧斯曼影響,多數信奉伊斯蘭教。

Emma:這樣的組合本身就很脆弱吧?

Julia:確實如此。一開始就有許多矛盾,塞爾維亞人在政治上佔據主導地位,讓克羅埃西亞人和斯洛文尼亞人感到被邊緣化。雖然名義上是統一的國家,但內部的裂痕一直存在。

二戰與游擊隊的崛起

Emma:然後到了二戰,一切都變得更加混亂。

Julia:沒錯。1941 年,軸心國入侵南斯拉夫,這個國家立刻崩潰。德國佔領了塞爾維亞,意大利控制了亞得里亞海沿岸,而克羅埃西亞則成為納粹扶植的傀儡國。

Emma:克羅埃西亞的烏斯塔沙(Ustaše)政權非常殘暴,對吧?

Julia:是的,他們對塞爾維亞人、猶太人和羅姆人進行了種族滅絕。同時,南斯拉夫內部也出現了幾個勢力——王室支持的 切特尼克(Chetniks) 想恢復君主制,而 鐵托領導的共產黨游擊隊 則想建立一個新的社會主義國家。

Emma:最後是鐵托獲勝了。

Julia:沒錯。到 1945 年,游擊隊成功趕走軸心國勢力,並推翻了君主制,建立了 南斯拉夫社會主義聯邦共和國,這是一個完全不同的南斯拉夫。

鐵托的南斯拉夫:統一還是假象?

Emma:所以,鐵托治下的南斯拉夫成為了一個共產主義國家。它的運作方式和蘇聯一樣嗎?

Julia:不完全一樣。1948 年,鐵托與史達林決裂,使南斯拉夫成為一個獨立於蘇聯的社會主義國家。因此,它發展出了一種獨特的社會主義模式,比東歐其他共產國家更有經濟靈活性。

Emma:但它仍然是共產國家,對吧?

Julia:是的,不過南斯拉夫比蘇聯開放得多。它與西方有較多經濟往來,還創立了 不結盟運動,試圖在冷戰的兩大陣營之間保持中立。

Emma:所以鐵托是靠個人魅力維持南斯拉夫的統一?

Julia:基本上是這樣。他的威望讓不同民族保持團結,但這種統一是表面的,民族間的矛盾一直沒有真正消失。

南斯拉夫的解體與戰爭

Emma:然後鐵托 1980 年去世後,情勢開始惡化?

Julia:是的。沒有了強人領導,南斯拉夫內部的經濟開始衰退,民族主義抬頭。到 1989 年,塞爾維亞的 斯洛博丹·米洛舍維奇(Slobodan Milošević) 開始推動中央集權政策,這讓克羅埃西亞和斯洛文尼亞感到威脅,於是他們決定脫離南斯拉夫。

Emma:然後戰爭爆發了。

Julia:沒錯。1991 年,斯洛文尼亞的獨立戰爭很短,但克羅埃西亞和波士尼亞的戰爭則慘烈得多,充滿了種族屠殺和圍城戰,比如薩拉熱窩的圍城就持續了將近四年。

Emma:這場戰爭讓原本共存的民族變成了敵人,真的很殘酷。

Julia:是的,這正是南斯拉夫解體的悲劇。那些曾經共同生活的人,最終成為了戰爭的對手。

南斯拉夫的遺產

Emma:塞爾維亞是最後一個放棄「南斯拉夫」身份的國家嗎?

Julia:可以這麼說。南斯拉夫解體後,塞爾維亞和蒙特內哥羅短暫組成「南斯拉夫聯邦」,但 2006 年蒙特內哥羅也宣布獨立。2008 年,科索沃單方面宣布獨立,不過塞爾維亞至今不承認。

Emma:現在還有人認為自己是「南斯拉夫人」嗎?

Julia:一些老一輩的人仍然懷念南斯拉夫時期,因為當時經濟較為穩定,民族間的關係也相對和平。但對年輕一代來說,南斯拉夫只是歷史。

Emma:這個國家的歷史簡直濃縮了整個 20 世紀的變遷——從帝國解體、戰爭、共產主義,到民族主義興起與國家分裂。

Julia:這就是為什麼南斯拉夫的歷史如此值得研究。它提醒我們,表面的統一並不代表真正的團結,而歷史的傷痕往往需要幾代人來修復。

他們沉思片刻,窗外的教堂鐘聲響起,彷彿歷史的迴聲仍然在貝爾格勒的空氣中迴盪。

Serbia’s Relations with Montenegro and North Macedonia

Their conversation shifts to Serbia’s relations with Montenegro and North Macedonia after the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Serbia and Montenegro: The Last Federation

Emma: We talked about the breakup of Yugoslavia earlier, but what about Serbia and Montenegro? They seemed to stick together longer than the others.

Julia: Yes, after the breakup, Serbia and Montenegro remained together as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FR Yugoslavia), which was formed in 1992. Later, in 2003, they rebranded it as the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro, which was already a sign that their ties were weakening.

Emma: So why did Montenegro eventually seek independence?

Julia: There were several reasons. While Montenegro and Serbia share a similar culture, language, and history, Montenegrins always had their own national identity.

Emma: But weren’t they historically part of the same country?

Julia: Yes, but historically, Montenegro was an independent principality until 1918, when it was absorbed into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, which later became Yugoslavia. During the Yugoslav era, Montenegro was a separate republic within the federation, not just a region of Serbia.

Emma: So they never fully identified as just being Serbian?

Julia: Exactly. And the wars of the 1990s pushed them further apart. The UN sanctions on Yugoslavia due to the conflicts in Croatia and Bosnia severely hurt Montenegro’s economy, and many Montenegrins felt that being tied to Serbia—especially under Milošević—was damaging their future.

Emma: So that’s why they held a referendum on independence?

Julia: Yes, in 2006, they held a referendum, and 55.5% of Montenegrins voted for independence. It was a very narrow margin, but it was enough. Serbia didn’t oppose it, and the split was peaceful.

Emma: And how are relations between Serbia and Montenegro today?

Julia: A bit tense. They still have strong trade and economic ties, but Montenegro joined NATO in 2017, which Serbia—and Russia—strongly opposed.

Emma: That must have created a political rift.

Julia: Definitely. And in 2019, Montenegro passed a controversial religious law that aimed to redistribute property belonging to the Serbian Orthodox Church, causing protests and further straining ties.

Emma: So, Montenegro is gradually distancing itself from Serbia?

Julia: Yes, they are trying to establish their own independent European identity.

Serbia and North Macedonia: Name, Identity, and Political Shifts

Emma: What about North Macedonia? It was also one of the republics in Yugoslavia, right?

Julia: Yes, back then, it was called the Socialist Republic of Macedonia, the southernmost part of Yugoslavia. When Yugoslavia broke up in 1991, Macedonia declared independence, but unlike Croatia or Bosnia, it did so peacefully, without a war.

Emma: But its name caused a lot of controversy, right?

Julia: Yes. Greece strongly objected to the use of “Macedonia" because Greece has a region with the same name. They feared that an independent “Republic of Macedonia" could make territorial claims on Greek land.

Emma: So that’s why they changed their name to “North Macedonia"?

Julia: Exactly. In 2019, the Prespa Agreement was signed, and the country officially became the Republic of North Macedonia, allowing them to improve relations with Greece and join NATO.

Emma: And where does Serbia stand on this issue?

Julia: Serbia has always had relatively stable relations with North Macedonia and didn’t interfere much in the name dispute. But they do have differences—especially over Kosovo.

Emma: How so?

Julia: In 2008, North Macedonia recognized Kosovo as an independent country, which angered Serbia. Serbia still considers Kosovo part of its territory, so when North Macedonia sided with the West, it caused tension between the two countries.

https://www.britannica.com/place/Kosovo

Emma: So North Macedonia is leaning more towards Europe?

Julia: Yes, it has been pushing for EU membership and aligns itself more with NATO and Western policies, rather than maintaining close ties with Serbia.

The Current State of Relations

Emma: So, if we look at these three countries today, how would you describe their relationships?

Julia: I’d say they share a common history but are choosing different futures.

Emma: Montenegro is pulling away from Serbia, and North Macedonia is integrating into Europe?

Julia: Exactly. Montenegro and North Macedonia both see their future in the EU and NATO, while Serbia remains caught between Europe and its historic ties to Russia.

Emma: It sounds like Yugoslavia’s collapse is still shaping the politics of today.

Julia: Absolutely. History in this region isn’t just something in books—it’s still unfolding. Even though these countries are independent, their relationships remain intertwined, for better or worse.

塞爾維亞與蒙特內哥羅:最後的聯邦

Emma:我們剛才聊了南斯拉夫的解體,那塞爾維亞和蒙特內哥羅的關係呢?他們不是一直待在一起嗎?

Julia:是的,在南斯拉夫解體後,塞爾維亞和蒙特內哥羅仍然維持了一個聯邦,最初叫 南斯拉夫聯盟共和國(FR Yugoslavia),1992 年成立。但 2003 年,他們改名為 塞爾維亞與蒙特內哥羅,這已經意味著他們之間的聯繫正在鬆動。

Emma:為什麼蒙特內哥羅後來還是選擇獨立呢?

Julia:有幾個原因。首先,蒙特內哥羅雖然和塞爾維亞在文化上相近,絕大多數人說塞爾維亞-克羅埃西亞語,也有很多共同的歷史,但他們一直有自己的民族身份。

Emma:但他們以前不是同屬一個國家嗎?

Julia:是的,但歷史上,蒙特內哥羅曾經是一個獨立的公國,直到 1918 年才被併入塞爾維亞王國。而且在南斯拉夫時期,蒙特內哥羅是獨立的加盟共和國之一,不是塞爾維亞的一部分。

Emma:所以他們並不完全認同「我們就是塞爾維亞人」?

Julia:沒錯。而且 1990 年代的戰爭讓蒙特內哥羅覺得和塞爾維亞綁在一起是個負擔。米洛舍維奇政權在國際上被制裁,影響了蒙特內哥羅的經濟,他們希望能有自己的外交政策,加入歐盟和北約。

Emma:所以他們舉行了獨立公投?

Julia:對,2006 年的公投以 55.5% 對 44.5% 的微弱多數通過獨立。塞爾維亞政府沒有干涉,最後和平分離。

Emma:所以現在塞爾維亞和蒙特內哥羅的關係如何?

Julia:有點緊張。雖然他們保持貿易和經濟往來,但蒙特內哥羅在 2017 年加入了北約,這讓塞爾維亞和俄羅斯都很不滿。另外,蒙特內哥羅政府在 2019 年通過了一項宗教法案,試圖重新分配塞爾維亞東正教會在該國的財產,引發了極大爭議。

Emma:所以蒙特內哥羅在慢慢疏遠塞爾維亞?

Julia:基本上是這樣。他們正在尋找自己的歐洲定位,和塞爾維亞的關係時好時壞。

塞爾維亞與北馬其頓:名稱、身份與政治角力

Emma:那北馬其頓呢?它在南斯拉夫時期也是加盟共和國之一,對吧?

Julia:對,當時它叫 馬其頓共和國(Socialist Republic of Macedonia),是南斯拉夫最南邊的一部分。1991 年南斯拉夫解體時,馬其頓獨立了,但過程和平,沒有像克羅埃西亞或波士尼亞那樣發生戰爭。

Emma:但我記得它的名字一直有爭議?

Julia:沒錯。馬其頓的名字引起了希臘的強烈反對,因為希臘北部有一個同名的地區,他們擔心這會影響領土主權。

Emma:所以後來改名為「北馬其頓共和國」?

Julia:對,2019 年,為了加入北約和歐盟,馬其頓政府和希臘簽署了《普雷斯帕協議》,改名為 北馬其頓共和國(North Macedonia)。

Emma:那塞爾維亞怎麼看這個問題?

Julia:其實塞爾維亞一直和北馬其頓保持相對穩定的關係,沒有特別干預馬其頓的內政。不過,在科索沃問題上,他們立場不同。

Emma:怎麼說?

Julia:北馬其頓在 2008 年承認了 科索沃獨立,這讓塞爾維亞非常不滿。科索沃對塞爾維亞來說仍然是國家主權的一部分,而北馬其頓選擇站在西方陣營這一邊,這影響了兩國的關係。

Emma:所以北馬其頓更親近歐洲?

Julia:是的。他們積極推動加入歐盟,和西方保持密切關係,與塞爾維亞的聯繫沒有蒙特內哥羅那麼深。

塞爾維亞、蒙特內哥羅和北馬其頓的現狀

Emma:總的來說,這三個國家現在的關係怎麼樣?

Julia:如果用一句話來形容,它們有著共同的歷史,但各自選擇了不同的未來。

Emma:蒙特內哥羅試圖與塞爾維亞保持距離,北馬其頓則積極尋求歐盟和北約的支持?

Julia:對。蒙特內哥羅和北馬其頓都希望更靠近西方,而塞爾維亞則在歐洲和俄羅斯之間保持平衡。這些國家曾經共享一個聯邦,但現在,它們各有自己的政治路線。

Emma:聽起來,南斯拉夫解體後的影響還沒有完全消散。

Julia:當然沒有。這片土地的歷史太深厚了,國家之間的關係總是牽一髮而動全身。即使他們已經分開了,彼此的影響仍然無法忽視。

Understanding the Post-Yugoslav States from a Foreigner’s Perspective

Emma and Julia stroll through the cobbled streets of Belgrade’s old town, Kalemegdan Fortress in the distance. They’ve been discussing the breakup of Yugoslavia, but now their conversation shifts to a more personal perspective—whether foreigners can feel the differences between the former Yugoslav republics.

Can a Foreigner Sense the Differences?

Emma: We’ve talked so much about the history and politics, but if a foreigner visits these countries today, would they actually feel the difference? Or would they all just seem… similar?

Julia: That’s a great question. To an outsider, many of the former Yugoslav republics might feel alike at first glance. They share similar languages, cuisine, and cultural traditions. But if you spend time in each place, the differences become clear.

Emma: So it’s not just one big “Yugoslavia 2.0″?

Julia: Not at all. Even when Yugoslavia existed, the regions had distinct identities. Belgrade feels different from Zagreb, and both feel different from Podgorica or Skopje.

Differences in Architecture and City Vibes

Emma: Let’s start with cities. What’s the biggest contrast between, say, Belgrade and Zagreb?

Julia: Belgrade has a more raw, chaotic energy. It’s a city that has been destroyed and rebuilt so many times that it has layers of architecture—Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, Communist, modern. The city feels alive, almost rebellious.

Emma: And Zagreb?

Julia: Zagreb is more Austro-Hungarian in style. It has that classic Central European feel, with elegant squares, orderly streets, and a more structured atmosphere. If you’ve been to Vienna or Budapest, Zagreb feels closer to that world.

Zagreb, Croatia, cityscape with Austro-Hungarian architecture

Emma: What about Montenegro?

Julia: That’s another contrast. Podgorica, Montenegro’s capital, is much smaller and less developed than Belgrade or Zagreb. It has a Soviet-style layout with a few modern touches. But if you go to the coast, like Kotor or Budva, it feels completely different—medieval stone towns, Venetian architecture, and a strong maritime influence.

Emma: So Montenegro is more like a mix of Balkan, Slavic, and Mediterranean cultures?

Julia: Exactly. The coastline feels more like Italy or Croatia, but inland, it’s more rugged and traditional.

Emma: And what about North Macedonia?

Julia: Skopje is unique. It has a mix of Ottoman, Byzantine, and brutalist Communist architecture. But in recent years, they built a lot of over-the-top neoclassical-style buildings, which gives the city a very surreal look.

Emma: So visually, you can definitely see the differences between these places?

Julia: Without a doubt.

Language and Identity Differences

Emma: But what about language? To me, Serbian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Bosnian all sound the same.

Julia: That’s because they basically are the same language—linguists call it the Serbo-Croatian continuum. But politically, each country calls it something different to reinforce their national identity.

Emma: So if I learn Serbian, I can understand Croatians and Montenegrins?

Julia: Yes, absolutely. The only real difference is in writing—Serbia still uses Cyrillic and Latin alphabets, while Croatia and Bosnia use only Latin.

Emma: And what about North Macedonia?

Julia: That’s a different language—Macedonian. It’s closely related to Bulgarian, and while Serbs can understand some of it, it’s not mutually intelligible like Serbian and Croatian are.

Cultural and Social Differences

Emma: What about daily life? Do the people behave differently in each country?

Julia: Definitely. Serbs tend to be warm, loud, and hospitable, but there’s also a bit of that Balkan defiance in their attitude. Croatians are a bit more reserved, and Montenegrins are famously laid-back—there’s even a joke that they are the most relaxed people in the Balkans.

Emma: Really?

Julia: Yes! In Montenegro, they have a saying: “If you see someone running, he’s probably a foreigner." They are known for taking life slowly.

Emma: That’s hilarious! And what about North Macedonia?

Julia: North Macedonia has a mix of Balkan and Mediterranean influences. It also has a large Albanian minority, which adds another cultural layer.

Food and Lifestyle

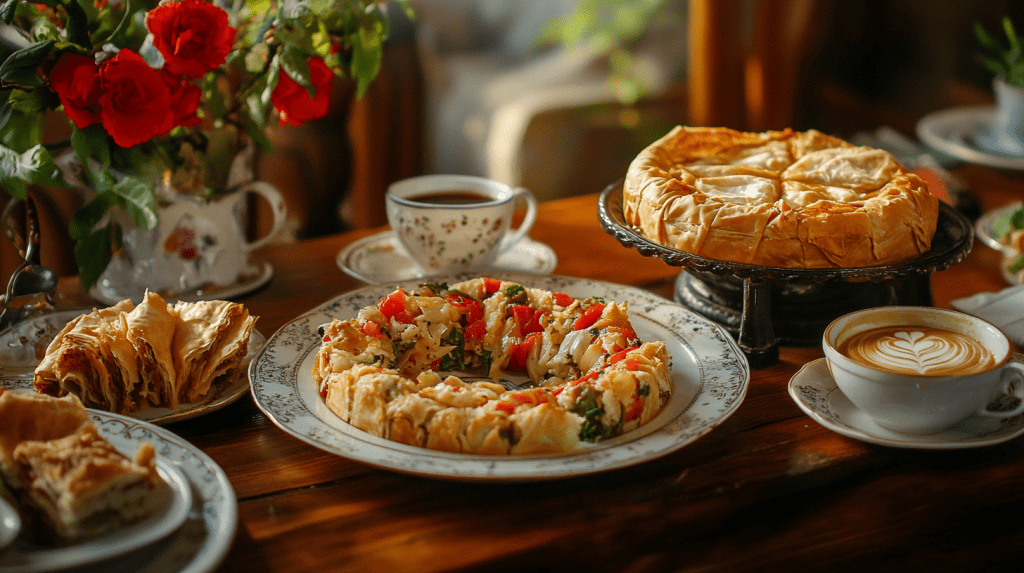

Emma: What about food? Is it all just “Balkan cuisine"?

Julia: There are definitely similarities—grilled meats, pastries, rakija (fruit brandy). But there are also regional differences.

- Serbia: Heavy on grilled meats, stews, and rakija. Serbian “ćevapi" (grilled minced meat) are famous.

- Croatia: Along the coast, food is more Mediterranean—seafood, olive oil, and wine. Inland, it’s more Central European.

- Montenegro: Coastal food is very Adriatic, similar to Croatia, while the inland diet is simpler, with heavy meats and dairy.

- North Macedonia: They have a strong Ottoman influence—lots of spicy peppers, stuffed vegetables, and Turkish-style sweets.

Serbian ćevapi, freshly grilled minced meat sausages

Traditional North Macedonian cuisine, Ottoman-influenced dishes, a rustic wooden table with stuffed peppers (polneti piperki), spicy ajvar, burek pastries, sarma (stuffed cabbage rolls), baklava.

Emma: So, even at the dinner table, you can taste the history?

Julia: Exactly. The cuisine reflects the different empires that ruled each region.

Political and Economic Differences

Emma: So, beyond culture, do these countries also feel politically different?

Julia: Definitely.

- Serbia is still balancing between the West and Russia.

- Croatia is fully integrated into the EU and NATO.

- Montenegro is in NATO but not yet in the EU.

- North Macedonia is in NATO and working toward EU membership, but faces obstacles.

Emma: And economically?

Julia: Croatia has the most developed economy because of tourism and its EU access. Serbia has a strong economy but is still outside the EU. Montenegro is highly dependent on tourism, while North Macedonia remains one of the poorer states in the region.

Conclusion: One Region, Many Identities

Emma: So, even though these countries were once united, today they are very different?

Julia: Yes. They share a common history but have taken different paths. A foreigner might not notice all the differences at first, but the more time you spend here, the more you realize how diverse the region truly is.

Emma: It’s fascinating. The Balkans are like a puzzle where all the pieces fit together, yet each has its own unique design.

Julia: That’s a perfect way to put it. And that’s why this region is so interesting—it’s complex, but that complexity is what makes it so special.

They continue their walk, passing a small café where the scent of grilled ćevapi fills the air. Around them, the city of Belgrade hums with energy, embodying the rich, layered history of the Balkans.

能感受到差異嗎?外國人眼中的前南斯拉夫國家

Emma 和 Julia 走在貝爾格勒老城區的石板路上,遠處的卡萊梅格丹城堡靜靜地矗立著。他們一直在討論南斯拉夫的歷史,但現在話題轉向更個人的觀察——外國人是否能感受到這些國家的不同?

外國人能察覺這些國家的差異嗎?

Emma:我們聊了這麼多歷史和政治問題,但如果一個外國人來到這些國家旅行,他們真的能感受到區別嗎?還是對外人來說,它們其實都很相似?

Julia:這是個好問題。對於不熟悉這個地區的人來說,南斯拉夫各國可能一開始看起來差不多——語言類似,食物相似,文化傳統也有很多共同點。但如果你在這裡待久了,你會發現每個地方都有自己的特色。

Emma:所以,這裡並不是一個「二代南斯拉夫」?

Julia:當然不是。即使在南斯拉夫時期,各地區的身份認同也不同。貝爾格勒和薩格勒布的感覺完全不一樣,而波德戈里察(Podgorica,蒙特內哥羅首都)或斯科普里(Skopje,北馬其頓首都)又是另一種風格。

建築與城市氛圍的不同

Emma:從城市的角度來看,貝爾格勒和薩格勒布的最大區別是什麼?

Julia:貝爾格勒有一種粗獷而充滿活力的感覺。這座城市歷經多次毀滅與重建,建築風格混雜——奧斯曼、奧匈帝國、社會主義和現代建築共存。整座城市充滿能量,甚至有點叛逆的氣質。

Emma:那薩格勒布呢?

Julia:薩格勒布的城市結構更接近奧匈帝國時期的歐洲大陸風格。這裡有典型的中央歐洲廣場、規整的街道,整個城市給人一種更典雅、有秩序的感覺。如果你去過維也納或布達佩斯,會覺得薩格勒布的氛圍和它們更接近。

Emma:那蒙特內哥羅呢?

Julia:這又是一個完全不同的世界。波德戈里察作為首都,規模小,發展程度比不上貝爾格勒或薩格勒布,城市結構有強烈的蘇聯影響。但如果你去海岸城市,比如科托爾(Kotor)或布德瓦(Budva),那裡的風格完全不同——充滿中世紀石砌城鎮、威尼斯建築和濃厚的海洋文化氛圍。

Podgorica, Montenegro, cityscape with a Soviet-era urban layout

Emma:所以,蒙特內哥羅就像是巴爾幹、斯拉夫和地中海文化的混合體?

Julia:沒錯。海岸地區像義大利或克羅埃西亞,而內陸則是更傳統的巴爾幹風格。

Emma:北馬其頓呢?

Julia:斯科普里(Skopje)是個奇特的城市。它融合了奧斯曼、拜占庭和社會主義建築,但最近幾年政府興建了許多浮誇的新古典主義建築,讓整個城市的風格變得非常奇特。

斯科普里(Skopje)拜占庭建築

Emma:所以光是從城市建築和氛圍,就能明顯感受到這些地方的不同?

Julia:當然。

語言與身份認同的不同

Emma:語言呢?對我來說,塞爾維亞語、克羅埃西亞語、蒙特內哥羅語和波士尼亞語聽起來幾乎一樣。

Julia:因為它們本質上是同一種語言——學術上稱為 塞爾維亞-克羅埃西亞語(Serbo-Croatian)。但每個國家都給自己的語言取了不同的名稱,以強化自己的民族身份。

Emma:所以,如果我學會塞爾維亞語,我就能聽懂克羅埃西亞人和蒙特內哥羅人在說什麼?

Julia:完全沒問題。唯一的顯著區別是書寫系統——塞爾維亞語同時使用 西里爾字母和拉丁字母,但克羅埃西亞和波士尼亞只用拉丁字母。

Emma:那北馬其頓呢?

Julia:北馬其頓語就比較不同了,它跟保加利亞語關係更近,塞爾維亞人能猜出一部分意思,但不像塞爾維亞語和克羅埃西亞語那樣互通。

文化與社會氛圍

Emma:在日常生活中,不同國家的人行為上有區別嗎?

Julia:有的。

- 塞爾維亞人:熱情、大方、好客,性格中帶有一種巴爾幹式的倔強與自豪感。

- 克羅埃西亞人:相較之下較為內斂,尤其是北方地區,文化上更接近中歐。

- 蒙特內哥羅人:以悠閒著稱,有句巴爾幹玩笑說:「如果你看到有人跑步,他可能是外國人。」

- 北馬其頓人:受奧斯曼與地中海影響,文化氛圍較為多元,民族構成也較為複雜。

飲食文化的不同

Emma:飲食方面呢?這些國家吃的東西很像嗎?

Julia:有相似的地方,但也有區別。例如:

- 塞爾維亞:以燒烤和燉菜為主,著名的「Ćevapi」(烤肉捲)非常受歡迎。

- 克羅埃西亞:沿海地區是地中海飲食,以海鮮、橄欖油和葡萄酒為主,內陸則更偏歐洲大陸風格。

- 蒙特內哥羅:海岸地區與克羅埃西亞類似,但內陸食物較簡單,肉類和乳製品為主。

- 北馬其頓:有更明顯的奧斯曼影響,愛吃辛辣的辣椒、填餡蔬菜,還有很多土耳其風味的甜點。

Emma:所以,即使是在餐桌上,也能品味出不同的歷史影響?

Julia:沒錯。

Traditional Croatian inland cuisine, a rustic wooden table with slow-cooked meats, hearty stews, štrukli (cheese-filled pastry)

傳統北馬其頓料理,受奧斯曼影響的美食,擺放在質樸的木製餐桌上,包括填餡辣椒(polneti piperki)、辛辣的 ajvar 醬、薄餅(burek)、葡萄葉包飯(sarma)、甜點如巴克拉瓦(baklava)和土倫巴(tulumba),搭配土耳其風格的咖啡。

結論:一個地區,多種身份

Emma:所以,即使這些國家曾經統一在南斯拉夫,它們現在已經變得非常不同了?

Julia:對。它們擁有共同的歷史,但現在正走向不同的未來。

Emma:這個地區就像一塊拼圖,每一塊都來自同一個整體,但又各具特色。

Julia:這正是巴爾幹的魅力。它複雜,但這種複雜性造就了它的獨特。

她們繼續前行,空氣中瀰漫著烤肉的香氣,貝爾格勒依舊充滿活力,見證著這片土地的歷史與變遷。

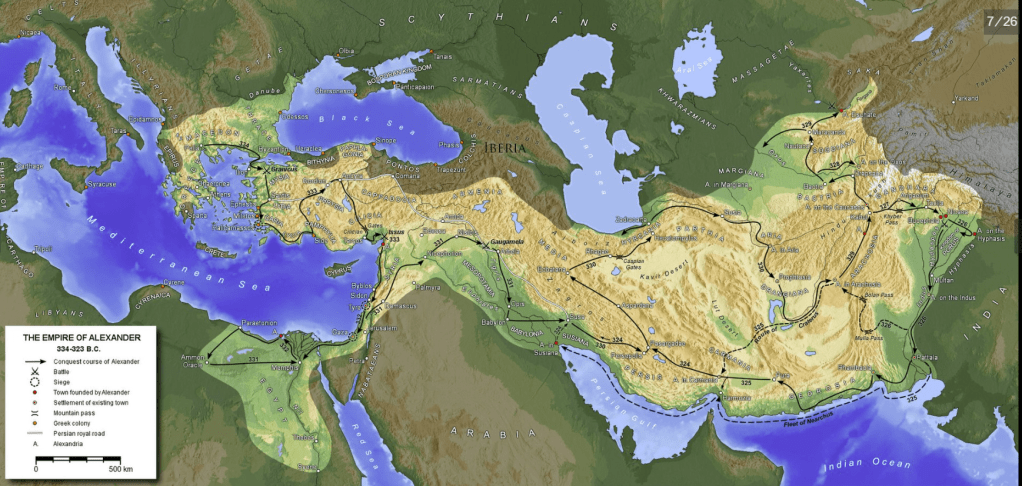

Alexander the Great: Macedonian or Greek?

In Front of Alexander the Great’s Statue in Skopje

Emma and Julia stand in the center of Skopje, the capital of North Macedonia, in front of the massive statue of Alexander the Great. The monument, erected in 2011, has been a major point of political controversy between North Macedonia and Greece.

Was Alexander Macedonian or Greek?

Emma: This statue is impressive. Alexander the Great is really celebrated here!

Julia: (Laughs) That’s exactly where the controversy begins. To North Macedonia, he is a national hero, but to Greece, he is absolutely Greek.

Emma: So, historically, where did he actually belong?

Julia: He was from the Kingdom of Macedon, which was located in what is today northern Greece, not in present-day North Macedonia. But culturally, the ancient Macedonians were heavily influenced by Greek civilization, and Alexander himself was educated in Greek traditions.

Emma: His tutor was Aristotle, right?

Julia: Exactly. His father, Philip II of Macedon, hired Aristotle to teach him, which shows how deeply connected Macedonian elites were to Greek philosophy, science, and military strategy.

Emma: But did they speak the same language as the Athenians or Spartans?

Julia: This is another debated issue. Macedonians spoke a Doric Greek dialect, which was different from the Attic Greek spoken in Athens. But they could still communicate with other Greeks, and Alexander himself used Greek as his main language.

How Did the Greeks View the Macedonians?

Emma: Since Macedonia and Greece were so close, how did the classical Greek city-states view them?

Julia: The powerful Greek city-states, especially Athens and Sparta, initially did not consider the Macedonians to be “real Greeks." They saw them as a semi-barbaric people from the northern frontier.

Emma: So they weren’t fully accepted?

Julia: No, but this perception changed when Philip II unified Greece under Macedonian rule. In 338 BC, he defeated Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea, effectively making Macedonia the dominant force in the Greek world.

Emma: So after that, Macedonia wasn’t just part of Greece—it ruled over Greece?

Julia: Exactly. And when Alexander inherited his father’s kingdom, he didn’t reject Greek culture—he embraced it and spread it throughout the Persian Empire, Egypt, and as far as India. His cities—like Alexandria in Egypt—were all based on Greek models.

The Modern Dispute: North Macedonia vs. Greece

Emma: So why is there still an argument about Alexander today?

Julia: It’s all about modern national identity. When North Macedonia gained independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, they named themselves the “Republic of Macedonia." This caused an immediate dispute with Greece.

Emma: Because Greece has a region called “Macedonia"?

Julia: Exactly. Greece argued that the ancient Kingdom of Macedon belonged to their historical heritage, and they feared that North Macedonia’s use of the name implied territorial claims.

Emma: So this statue was built in the middle of that controversy?

Julia: Yes, in 2011, North Macedonia’s government built this giant statue of Alexander in Skopje, which outraged Greece. Greeks saw it as “historical appropriation", arguing that Alexander and his kingdom were Greek, not Slavic. This dispute led Greece to block North Macedonia from joining NATO and the EU.

Emma: So how was the issue resolved?

Julia: In 2019, North Macedonia signed the Prespa Agreement with Greece, officially changing its name to the “Republic of North Macedonia." This finally allowed them to join NATO.

Conclusion: Who Does Alexander Belong To?

Emma: So, the final question—was Alexander a Macedonian or a Greek?

Julia: (Smiles) That depends on whom you ask. If you ask a Greek, they’ll say, “He was Greek because Macedon was part of the Greek world. He spoke Greek, spread Greek culture, and ruled over the Greek city-states." If you ask someone from North Macedonia, they might say, “He was Macedonian, and our country is the continuation of that legacy."

Emma: But from a historian’s perspective?

Julia: Historically, Alexander was the king of Macedon, a Greek-speaking kingdom heavily influenced by Greek culture. He received a Greek education, led Greek armies, and expanded Greek civilization. However, his kingdom was distinct from the traditional city-states like Athens and Sparta.

Emma: So he was both Macedonian and a promoter of Greek culture?

Julia: That’s a fair way to put it. His identity is complex, which is why the debate will never truly end.

Emma: I guess some historical figures are destined to be controversial forever.

Julia: Absolutely. Alexander the Great, like the Balkans themselves, is a mix of identities, history, and politics.

They glance up at the towering statue, the inscription reading “Alexander the Great – Conqueror of the World," standing as a reminder that history is never just the past—it’s still alive in the present.

亞歷山大大帝:馬其頓人還是希臘人?

斯科普里市中心,亞歷山大大帝雕像前

Emma 和 Julia 站在北馬其頓首都斯科普里(Skopje)市中心,巨大的亞歷山大大帝雕像矗立在廣場上。這座雕像是 2011 年政府為強調北馬其頓與亞歷山大大帝的聯繫而建造的,當時曾引發與希臘的政治爭議。

亞歷山大到底是馬其頓人還是希臘人?

Emma:這座雕像好壯觀,亞歷山大大帝在這裡真的是民族英雄啊!

Julia:(笑)這正是爭議的核心。對北馬其頓來說,亞歷山大是馬其頓的象徵,但對希臘來說,他絕對是希臘人。

Emma:所以,歷史上他到底是哪一方的?

Julia:他來自 馬其頓王國(Kingdom of Macedon),這個王國位於今天的希臘北部,與現在的「北馬其頓共和國」不是同一個概念。但馬其頓王國在文化上深受希臘影響,亞歷山大本人也接受了希臘文化教育。

Emma:他的老師不是亞里士多德嗎?

Julia:沒錯。他的父親 腓力二世(Philip II) 讓亞里士多德擔任他的家庭教師,這代表馬其頓王國的貴族階級高度希臘化。亞歷山大通過希臘語學習哲學、科學和軍事戰略,他也崇尚希臘文化。

Emma:但他們講的語言和雅典或斯巴達人是一樣的嗎?

Julia:這也是一個爭論點。馬其頓人說的是一種 多利安方言(Doric dialect),這與古典希臘城邦的雅典方言有所不同。但古代希臘人能理解馬其頓語,而亞歷山大本人確實以希臘語溝通。

希臘人如何看待馬其頓人?

Emma:既然馬其頓王國與希臘這麼接近,當時的希臘人怎麼看待他們?

Julia:古典時期的希臘城邦,尤其是雅典和斯巴達,一開始不認為馬其頓是「真正的希臘人」。他們覺得馬其頓人是邊疆民族,文化上不如雅典民主、也不像斯巴達軍事化。

Emma:所以馬其頓王國當時不被希臘人完全接受?

Julia:對,但這個觀點在腓力二世統一希臘後開始改變。公元前 338 年,腓力二世在喀羅尼亞戰役(Battle of Chaeronea)擊敗了雅典和底比斯,成為希臘世界的主導者。 從此,馬其頓王國正式統治了希臘。

Emma:也就是說,從那時起,馬其頓不只是希臘的一部分,而是它的統治者?

Julia:可以這麼說。亞歷山大繼承父親的帝國後,不僅沒有排斥希臘文化,反而將希臘化世界擴展到了整個波斯、埃及和印度邊界。他建立的城市——亞歷山卓(Alexandria)——都以希臘文化為基礎。

現代的爭議:北馬其頓 vs 希臘

Emma:那為什麼今天北馬其頓和希臘會為亞歷山大吵架?

Julia:這與現代國族認同有關。北馬其頓的前身是南斯拉夫的一部分,當 1991 年從南斯拉夫獨立時,他們選擇了「馬其頓共和國」這個名字,但這讓希臘非常不滿。

Emma:因為希臘北部有個「馬其頓」地區?

Julia:沒錯。希臘人認為,「馬其頓」這個詞應該只屬於古代馬其頓王國的歷史,而這個王國的核心區域位於今天希臘的馬其頓省(包括塞薩洛尼基)。希臘擔心北馬其頓使用這個名字會暗示領土主張或文化侵占。

Emma:那這座雕像就是在這場爭議中出現的?

Julia:是的。2011 年,北馬其頓政府在斯科普里建了這座巨大的亞歷山大雕像,希臘人認為這是「文化挪用」,因為亞歷山大和他的王國屬於希臘歷史。這場爭議導致希臘 阻撓北馬其頓加入歐盟和北約。

Emma:所以,最後北馬其頓怎麼解決這個問題?

Julia:2019 年,他們與希臘簽署了《普雷斯帕協議(Prespa Agreement)》,將國名改為 「北馬其頓共和國(Republic of North Macedonia)」,這才打破僵局,成功加入北約。

結論:亞歷山大屬於誰?

Emma:那麼,最後的問題——亞歷山大到底是馬其頓人,還是希臘人?

Julia:(笑)這取決於你的觀點。如果你問一個希臘人,他們會說:「他是希臘人,因為馬其頓王國是希臘世界的一部分,他講希臘語,他推廣希臘文化。」如果你問一個北馬其頓人,他們會說:「他來自馬其頓,這就是我們的根。」

Emma:但從歷史角度來看呢?

Julia:歷史上,亞歷山大大帝來自馬其頓王國,這個王國是希臘文化圈的一部分。他接受希臘教育、說希臘語、崇尚希臘哲學,並推動希臘文化擴張。但他的民族身份與典型的雅典人、斯巴達人或底比斯人不太一樣。

Emma:所以,他既是馬其頓人,也是一位希臘文化的推動者?

Julia:可以這麼說。他的歷史定位,最終取決於你如何定義「希臘人」。

Emma:這場爭論大概永遠不會結束吧?

Julia:沒錯。亞歷山大就像這片土地的歷史一樣,充滿爭議,但也是這種複雜性讓巴爾幹如此迷人。

他們看著雕像下的刻字,「亞歷山大大帝——世界征服者」,這位傳奇人物的身影,在今日的爭議中仍舊屹立不搖。

發表留言