Morning Plans

The sun was up early, and so were they. In the breakfast room, warm bread and sliced cheese were already waiting on the sideboard, along with boiled eggs, a plate of smoked salmon, and a pot of black coffee.

Julia wrapped her hands around her cup. “So… we’re heading south today?”

Tomas nodded. “Yes, we’ll take the main road down to Nida. Should take about 40 minutes, but we’ll probably want to stop once or twice.”

Emma looked up from her plate. “What’s along the way?”

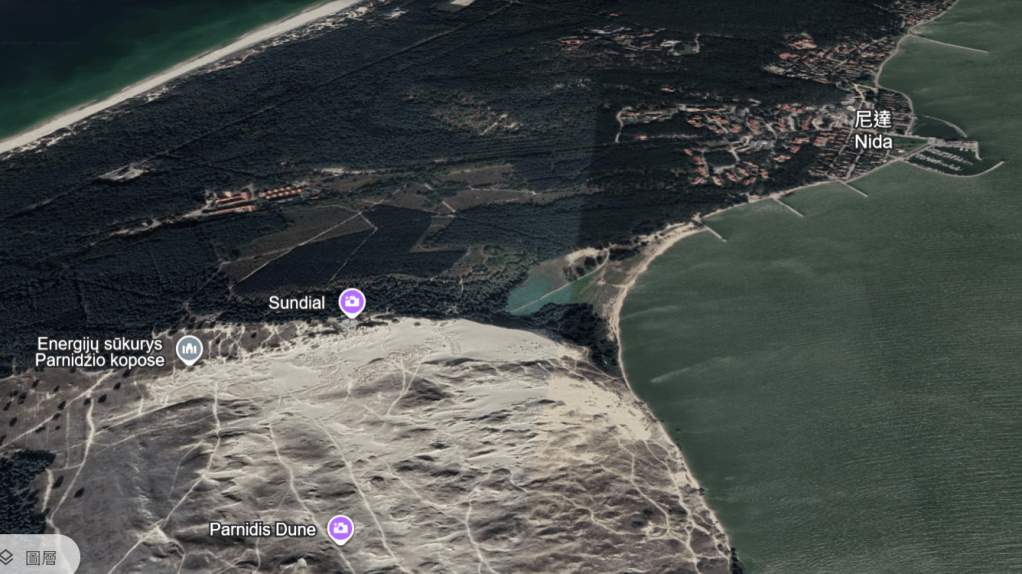

“Well,” Tomas began, reaching for a boiled egg, “we’ll pass by the Dead Dunes — shifting sand hills that have swallowed entire villages in the past. Then we can stop at the Parnidis Dune, near Nida. There’s a huge sundial there, and from the top, you get a clear view of both the lagoon and the open sea.”

Ben looked interested. “And it’s all on this narrow strip of land, right?”

“Exactly,” said Tomas. “The spit is barely 2 kilometers wide at some points. On one side, calm lagoon. On the other, the Baltic Sea.”

Renata was spreading butter on a slice of rye bread. “Sounds like a place where the wind tells stories.”

Tomas smiled. “And the sand remembers them.”

They finished their meal with no rush. It was the kind of morning that made you want to linger — clear light, quiet voices, and the steady sense that something beautiful was waiting ahead.

早晨出發前的計畫

太陽很早就升起了,他們也起得不晚。民宿的早餐餐廳裡,已經擺好了溫熱的黑麥麵包、幾種起司、水煮蛋、一盤煙燻鮭魚,還有一壺剛煮好的黑咖啡。

茱莉亞雙手捧著咖啡杯問:「所以……今天是往南邊走?」

托馬斯點點頭:「對,我們會順著主路往 Nida 去,大概四十分鐘,不過應該會中途停一兩站。」

艾瑪邊吃邊問:「沿路會經過什麼?」

「首先會經過“死亡沙丘”(Dead Dunes),」托馬斯夾起一顆水煮蛋說,「那些移動的沙丘曾經掩埋過整個村莊。然後可以在帕納卡沙丘(Parnidis Dune)停一下,那裡有座大型日晷,從高處可以同時看到潟湖與波羅的海。」

班有點好奇地說:「這整段都是在那條細長的沙地上對吧?」

「對,」托馬斯笑著說,「最窄的地方只有兩公里寬。一邊是靜靜的潟湖,另一邊是波濤的海。」

雷娜塔抹著奶油,笑著說:「感覺是風在說故事的地方。」

托馬斯說:「還有沙在記住它們。」

他們慢慢吃完早餐,沒有急著動身。這是一種讓人想多停留一下的早晨——清亮的光線、低低的對話聲,以及一種穩穩的預感:前方會很美。

On the Road to Nida

They loaded the car slowly, taking time to make sure everything was packed — jackets, cameras, field notebooks, and a bag of leftover rye bread.

The road ran close to the lagoon at first, then cut gently through clusters of pine. To the right, dunes occasionally rose like pale humps beyond the trees; to the left, glimpses of water flashed silver in the morning light.

Julia sat in the front seat, looking out the window. “This part of the world feels… narrow. Like the land itself is walking a tightrope.”

Tomas nodded as he drove. “That’s not too far off. Some parts of the spit are less than two kilometers wide.”

Ben, in the back seat with his camera on his lap, asked, “Do people ever worry about it disappearing? Like, washed away?”

Tomas glanced at the mirror. “It’s a real concern. Especially during storms. The dunes are constantly moving — that’s why some villages in the 18th and 19th centuries had to be abandoned.”

Emma looked out at a long ridge of sand beyond the trees. “So the land has to be protected from both wind and water?”

“Exactly,” said Tomas. “There’s a whole system of planted forest and grass to hold the sand in place. It’s part ecology, part memory.”

Renata added, “It feels strange to drive through something so fragile.”

No one responded right away. Outside, the landscape remained quiet — just trees, sky, and a sense of long history beneath the sand.

往尼達的路上

他們不急不徐地將行李搬上車——外套、相機、田野筆記本,還有一袋沒吃完的黑麥麵包。

公路起初貼著潟湖邊緣延伸,接著轉入一段穿過松林的路段。右側偶爾可以看到沙丘如淺色的丘陵出現在樹叢後方;左側則是潟湖偶爾閃現的銀光,在早晨的陽光下微微晃動。

茱莉亞坐在前座,看著窗外說:「這一帶給人的感覺……很窄,好像整塊土地都在走鋼索。」

托馬斯一邊開車一邊點頭:「這形容蠻貼切的。有些地方沙嘴寬度甚至不到兩公里。」

班坐在後座,膝上抱著相機,問:「會不會有被海沖掉的風險?」

托馬斯從後照鏡看了一眼說:「確實有這個風險。尤其是暴風時。沙丘一直在移動——以前在十八、十九世紀,就有村莊因為這樣被迫放棄。」

艾瑪望著右側樹林外那條細長的沙脊說:「所以這片地要防的是風,也要防水?」

「沒錯,」托馬斯說,「整個沙嘴有種植松林與草地的系統,用來穩住沙。這既是生態工程,也是歷史的記憶。」

雷娜塔輕聲說:「開在這樣脆弱的地方,感覺有點不真實。」

大家一時之間沒有回話。窗外只有森林、天空,還有一種安靜地藏在沙下的歷史感。

Stop at the Shifting Dunes

About twenty minutes into the drive, Tomas slowed down and pulled into a small gravel turnout. A wooden sign marked the spot: Naglių Gamtos Rezervatas — Nagliai Nature Reserve.

“This is one of the dead dune areas,” he said, turning off the engine. “We won’t go far, just enough to stretch our legs.”

They followed a narrow boardwalk into the sand. On both sides, short pine and wind-blown grass held the pale surface together. Further ahead, a long, low ridge of dunes sloped up against the sky.

Ben lifted his camera but paused. “It’s not the view — it’s the space. You feel small.”

Emma nodded. “And temporary.”

Julia crouched and ran her hand over the sand. “It’s fine, almost powder. Hard to believe people lived here.”

“They didn’t for long,” Tomas said. “The sand buried them.”

Renata stood quietly, then said, “I read that this part of the spit is sometimes called a desert.”

Tomas smiled. “A Baltic desert. With memories under every hill.”

短暫停留:移動沙丘區

開了大約二十分鐘,托馬斯把車慢慢開進一處碎石停車區。木牌上寫著:Naglių Gamtos Rezervatas —— 納格利亞自然保護區。

「這是其中一段“死亡沙丘”,」他熄火說道,「我們不走太遠,就下去走走,活動一下筋骨。」

他們沿著一條窄窄的木棧道走進沙地。兩側是低矮的松樹與被風吹得東倒西歪的草,把一層淺色沙面穩穩壓住。再遠一點,一整道沙脊像背對天空的長坡。

班舉起相機,又放下來:「不是畫面,是空間感……你會覺得自己很渺小。」

艾瑪點點頭:「而且很短暫。」

茱莉亞蹲下來,用手撫過沙面:「很細,幾乎像粉……很難相信這裡曾經有人住過。」

「也沒住太久,」托馬斯說,「這些沙把整個村莊埋了。」

雷娜塔安靜了一會兒才說:「我看過,有人把這裡叫波羅的海的沙漠。」

托馬斯笑了一下:「波羅的沙漠,每一座丘陵下面都有故事。」

Why Are There Dunes Here?

Julia stood near the top of the low ridge, squinting into the wind.

“It’s interesting,” she said, “how such large dunes formed here, of all places.”

Ben glanced at her. “What do you mean? It’s near the sea, isn’t that normal?”

“Yes and no,” Julia replied. “Not every coastline has dunes like this. You need a specific combination — a shallow seabed, strong coastal winds, and very little rock. And above all, time.”

Tomas added, “And vegetation. The lack of it, or the wrong kind. Once a patch of grass dies off, the wind takes over.”

Emma looked at the slope. “So this whole spit… was built by wind?”

“More or less,” Julia said. “Post-glacial processes, mostly. The Curonian Spit is made from material pushed by waves and redistributed by wind. It’s a very young landscape, geologically speaking — fragile and still changing.”

Renata raised an eyebrow. “And yet people tried to live here?”

“People always try to live where they shouldn’t,” Julia said, half smiling. “But I think it says something about how adaptable we are.”

Tomas nodded. “Or how stubborn.”

這裡為什麼會有沙丘?

茱莉亞站在低矮的沙丘頂上,眯著眼迎著風。

「很有意思,」她說,「為什麼偏偏在這種地方,會有這麼大的沙丘。」

班轉頭看她:「不是靠海嗎?這樣不是很正常?」

「也不全是,」茱莉亞解釋,「不是所有的海岸線都有這種沙丘。你得有一整套條件——淺海底、穩定的海風、很少的岩石地形,最重要的還是……時間。」

托馬斯補充:「還有植被。如果草一死,風就開始動手了。」

艾瑪看著坡面說:「所以整個沙嘴……都是風造出來的?」

「大致是,」茱莉亞點頭,「大部分是冰河時期之後的堆積作用。這整條 Curonian Spit 是由海浪推來的沉積物,然後再被風吹動重新分佈。從地質角度來說,這是一塊非常年輕的地形——還在變動,還很脆弱。」

雷娜塔挑了挑眉:「可人們還是住進來?」

「人總是喜歡住在不該住的地方,」茱莉亞笑了一下,「但這也證明我們真的很有適應力。」

托馬斯點點頭:「也可能只是固執。」

Should People Live Here?

They stood still for a moment, the wind brushing past their jackets.

Julia glanced across the dunes and said, “Honestly, if you ask a geographer whether people should live here — the answer is usually no.”

Ben raised an eyebrow. “Too unstable?”

“Exactly. The land is mobile. The dunes shift over time — decades, sure, but that still affects roads, houses, infrastructure. And every solution we build — fences, trees, artificial barriers — eventually needs maintenance or fails.”

Tomas added, “That’s why there are no new developments allowed in most parts of the spit. Everything is highly regulated.”

Emma asked, “But people do live in Nida, right?”

“True,” Julia nodded. “But Nida is built on relatively more stable ground, and it’s heavily protected. Limited expansion, strict building codes, environmental zoning. In a way, it’s living by permission of the land.”

Renata smiled. “Sounds like living with one foot on the sand, the other in bureaucracy.”

Tomas laughed. “That’s actually a good description.”

應不應該住在這裡?

他們站在原地不動,風輕輕吹過外套。

茱莉亞看著眼前一片沙丘說:「如果你問一個地理學家:這種地方該不該住人——通常的答案是:不太適合。」

班挑眉:「太不穩定?」

「沒錯,」茱莉亞點頭,「這片地是會移動的。沙丘會改變形狀,可能要幾十年,但那會影響道路、房子、甚至整個基礎建設。我們用的所有對策——種樹、設圍欄、加固——最終都要維修,或者會失效。」

托馬斯接著說:「所以沙嘴大部分區域禁止新建,幾乎都是嚴格控管的。」

艾瑪問:「但 Nida 那邊不是有小鎮?」

「有,」茱莉亞點頭,「不過那一區的地基相對穩定,而且整個城鎮都受到保護。有很嚴格的建築規範、擴建限制、環境分區。某種程度上,那是在’土地同意下’才能住的地方。」

雷娜塔笑著說:「聽起來像是:一隻腳踩在沙上,另一隻踩在申請文件上。」

托馬斯笑出聲:「這形容得蠻準。」

Has This Area Always Been Inhabited?

Renata looked out over the dunes and asked, “Tomas, has anyone always lived here? Or was it something modern — like a tourism development?”

Tomas shook his head. “There have been settlements on the spit for centuries. Not continuous everywhere, but Neringa — the collective name for all the villages here — has existed in some form since the 14th or 15th century.”

Julia added, “Even the Teutonic Order had maps that marked this strip.”

Tomas nodded. “Some of the early communities were fishermen and beekeepers. They adapted to the shifting land. Others, especially around Nida, became more structured later on, especially in the 19th century when German artists and scientists started visiting.”

19th-century fishing scene in Nida, Curonian Spit

Ben said, “So tourism isn’t that new here.”

“Nope,” Tomas said. “The Germans used to call it the ‘Lithuanian Riviera’. And the dunes — especially the moving ones — were already a fascination a hundred years ago.”

Emma asked, “And now? Are there still long-term locals?”

Tomas smiled. “Yes, but fewer. Some families have lived here for generations. Others moved in after World War II when borders shifted. Today, many locals work in tourism, education, or ecological protection.”

這裡一直以來都有人住嗎?

雷娜塔看著遠方的沙丘問:「托馬斯,這裡一直以來都有人住嗎?還是後來才開發出來的,像是觀光用?」

托馬斯搖搖頭:「沙嘴上幾個聚落其實已經有幾百年歷史了。不是每一個地點都持續有人住,但像 Neringa 這整個區域,其實早在十四、十五世紀就有人定居。」

茱莉亞補充:「條頓騎士團那時候的地圖上就標出這條沙嘴了。」

托馬斯點頭:「早期有些社群是靠捕魚、養蜂維生的。他們慢慢適應這種會移動的地形。到了十九世紀,像 Nida 那一帶就開始有比較穩定的聚落,當時很多德國藝術家和學者開始來這裡寫生、做研究。」

十九世紀的 Nida 村莊 (想像)

班說:「所以觀光也不是什麼新東西了。」

「完全不是,」托馬斯笑了笑,「以前德國人甚至叫這裡『立陶宛的里維埃拉』。這些會移動的沙丘,一百年前就是熱門景點。」

艾瑪問:「那現在呢?還有在地人住這裡嗎?」

托馬斯點頭:「有的,但人越來越少。有些家庭是幾代人都住在這裡;也有一些是在二戰後搬來的,因為邊界變動。現在大多數本地人從事觀光業、教育、或生態保護。」

Arrival in Nida

As they drove further south, the road leveled out, and more houses began to appear — wooden cottages painted in dark reds and deep blues, with white window frames and tidy little gardens.

A narrow sign at the roadside read Nida. The trees thinned, and soon the Curonian Lagoon reappeared on their left, wide and calm.

“Feels more like a town now,” Julia said, adjusting her seatbelt.

Renata looked out. “And not just any town. This place has style.”

Tomas smiled. “Most of these houses were rebuilt or restored after World War II, many in the traditional style — half-timbered, low roofs, painted wood. A lot of them are summer homes now, but some are still lived in year-round.”

They passed a small marina, where a few sailboats rocked gently in the quiet water. Nearby, an old fisherman’s hut had been turned into a museum. A café had already set out outdoor tables, even though the air still had a spring chill.

Ben leaned forward. “Where are we staying?”

Tomas pointed toward a side street. “A guesthouse just off the main road. Nothing fancy, but it has a good view of the water.”

抵達尼達

隨著車子往南駛近,路變得平坦,兩旁開始出現更多房子——木造小屋塗成深紅或暗藍,搭配白色窗框與整齊的小花園。

路邊一塊窄小的標示寫著:Nida。樹林逐漸稀疏,左側的潟湖又重新映入眼簾,寬闊而平靜。

「這裡終於有鎮的感覺了,」茱莉亞調整安全帶說。

雷娜塔望著窗外:「而且不是普通的鎮。這裡很有味道。」

托馬斯微笑著說:「大部分房子是在二戰後重建或修復的,很多都保留傳統樣式——木架結構、低屋頂、漆上深色木料。現在有不少是夏季度假屋,但也有居民常住。」

他們經過一個小小的碼頭,幾艘帆船在安靜的水面上輕輕晃著。不遠處,一間舊漁夫小屋被改建成了博物館;附近一間咖啡館已經把戶外座位擺出來,儘管空氣還帶著一點春末的涼意。

班往前探身問:「我們住哪裡?」

托馬斯指了指一條支路:「主街旁邊有一家民宿。不算豪華,但可以看到潟湖。」

Why the German Look?

They were walking slowly along the street, past a row of low wooden houses. The air smelled faintly of sea and pine. One house had a little carved bird on the roof beam, another had white lace curtains in the windows.

Ben pointed at one of them. “These look… almost German?”

Emma nodded. “They are. This whole region used to be part of East Prussia. Nida, like the rest of the Curonian Spit, was under German control until the end of World War I.”

Julia added, “Even after that, it stayed very German in character. The architecture, the language, even the schools. Most of the buildings we’re seeing were built in the late 19th or early 20th century.”

Renata looked surprised. “So this wasn’t always Lithuanian?”

Tomas said, “Politically, no. Ethnically, it’s even more complex. You had Germans, Lithuanians, Curonians, even some Kashubians — mixed together across centuries.”

Emma gestured toward a house with exposed wooden beams. “And you see that in the buildings. The timber framing, the roof pitch, the painted woodwork — all very East Prussian, but adapted to local materials.”

Ben asked, “Did people keep speaking German here?”

“For a long time, yes,” Tomas said. “Even after borders changed. It faded out gradually — partly through Soviet policy, partly migration. But some older families in the area still remember the dialects.”

Julia said, “It’s one of those places where borders changed, but the walls remained the same.”

為什麼這裡看起來像德國?

他們沿著街道慢慢走,兩旁是一排排低矮的木屋。空氣中有淡淡的海味與松香。有間屋頂上刻了一隻小鳥,另一間窗邊掛著白色蕾絲窗簾。

班指著其中一棟說:「這些房子……怎麼看起來有點像德國?」

艾瑪點頭說:「沒錯。這一區以前是東普魯士的一部分。包括 Nida 在內的整個 Curonian Spit,在第一次世界大戰結束前都是德國統治。」

茱莉亞補充:「即使在政權轉移後,這裡還是保留很強的德國文化色彩。像建築風格、語言,甚至連學校都維持原樣。我們現在看到的很多房子,是十九世紀末或二十世紀初蓋的。」

雷娜塔有些驚訝:「所以這裡以前不是立陶宛的?」

托馬斯說:「政治上不是。族群上更複雜——德國人、立陶宛人、庫羅尼亞人,甚至有些是卡舒比人,這一帶本來就是混居的。」

艾瑪指著一棟露出木架結構的房子說:「像這些建築——木架結構、屋頂斜角、漆木外牆——都很東普風格,但有用在地的建材去調整。」

班問:「那以前的人還講德語嗎?」

「講,很久以前還是常見語言,」托馬斯說,「邊界變了,人還在。後來才慢慢淡出,有一部分是蘇聯政策的影響,也有些人離開了。不過現在還有少數家庭記得那些老德語方言。」

茱莉亞說:「這就是那種——邊界改了,但房子的牆還在的地方。」

Coffee, Cake, and Questions of Germany

They found a small café just off the main street — a low wooden building with wide windows and simple white curtains. Inside, the scent of coffee and warm apple cake filled the air.

They sat down at a table near the window. A young woman behind the counter brought them slices of cake topped with sour cream and a pot of fresh coffee.

“This feels very… Central European,” Emma said, sipping from her cup.

Tomas nodded. “That’s not surprising. This town was East Prussia not too long ago. But people’s relationship with Germany is… layered.”

Renata asked, “You mean because of the war?”

“Partly,” Tomas replied. “There’s a distinction. Older families here remember German schools, German neighbors. But the German occupation during World War II was different — harsher, more political. Then came the Soviets, and all of that was erased, at least officially.”

Julia said, “So is there still a cultural tie?”

Tomas nodded slowly. “Yes, but it’s changed. There are still German tourists, especially in the summer. And quite a few young people go to Germany for university or work — better pay, more opportunities. But it’s more practical now than emotional.”

Ben asked, “So no nostalgia?”

Tomas smiled. “Some, maybe. For the architecture, the old calm life. But no one wants the past back — not the empires, not the borders.”

咖啡、蛋糕,與德國的記憶

他們在主街旁找到一家小咖啡館——低矮的木屋,大窗戶掛著簡單的白窗簾。屋內飄著咖啡與熱蘋果蛋糕的香氣。

他們選了靠窗的一張桌子坐下。櫃檯後的年輕女店員送來幾塊蛋糕,上面淋著酸奶油,還有一壺剛煮好的咖啡。

艾瑪喝了一口說:「這裡的感覺,很中歐。」

托馬斯點頭:「不奇怪。這個小鎮距離當年的東普魯士記憶不算遠。但人們對德國的情感……是有層次的。」

雷娜塔問:「你是說因為戰爭的關係?」

「部分是,」托馬斯回答,「老一輩的人記得德語學校、德國鄰居。但二戰時期的德國占領是另一回事——比較強硬,政治化。後來蘇聯來了,所有這些記憶就被‘官方抹掉’了。」

茱莉亞問:「那現在還有文化上的連結嗎?」

托馬斯慢慢點頭:「有,但已經不一樣了。每年夏天還是有不少德國遊客會來。有些年輕人也會去德國唸書、工作——因為機會多、待遇好。現在的連結更多是實際上的,而不是情感上的。」

班問:「那有沒有人對德國有懷舊情緒?」

托馬斯笑了一下:「或許有一點,對老建築、對某種寧靜的生活方式。但沒有人真的想回去那個時代——不管是帝國,也不管是變動中的國界。」

Soviet Memories and the Russian Question

The conversation drifted naturally.

Julia stirred her coffee. “What about the Soviet period? I mean, it shaped so much of this region.”

Tomas exhaled lightly. “That’s a harder memory. For people over forty, the Soviet era wasn’t history — it was life. Schools, jobs, language… all in Russian. It was the air you breathed.”

Nida in 1970s

Ben asked, “So do most people still speak Russian here?”

Tomas nodded. “Older generations, yes. And many still use it — to watch TV, talk to neighbors, or travel. But in schools now, Russian is fading. Kids learn English or German instead.”

Emma asked, “And emotionally? Is Russia still seen as close, or more like… something to stay away from?”

Tomas didn’t answer immediately. Then he said, “There’s resentment, definitely. Especially after 1990, and even more after what happened in Ukraine. For many Lithuanians, Russia represents pressure, loss of independence.”

Renata added quietly, “But it’s complicated, isn’t it? You grow up with a language, a rhythm of daily life… and then you’re told it’s part of what oppressed you.”

Tomas nodded again. “Exactly. So it becomes private — people might still use Russian at home, but not in public. Not proudly.”

Julia looked out the window. “And yet the buildings, the roads, the systems… all still carry the imprint.”

Tomas finished his coffee. “You can leave an empire. But it takes longer to get the empire out of you.”

蘇聯的記憶與俄羅斯問題

話題自然轉了過去。

茱莉亞慢慢攪著咖啡說:「那蘇聯時期呢?這裡的生活方式應該也被那段歷史影響很多吧?」

托馬斯輕輕嘆了一口氣:「這段就比較難說了。對四十歲以上的人來說,蘇聯不是歷史——那是生活。學校、工作、語言……全部是俄語,那是一種籠罩日常的空氣。」

1970 年代的 Nida

班問:「所以現在還有很多人會講俄語?」

托馬斯點點頭:「老一輩幾乎都會,很多人現在還在用——看電視、跟鄰居聊天、去外地旅行。但學校裡就不一樣了。現在的學生比較多學英文或德文。」

艾瑪問:「那情感上呢?俄羅斯對這裡來說,是還親近,還是越來越想避開?」

托馬斯沒馬上回答,過了一會才說:「確實有怨懟。尤其是從 1990 年獨立之後,更不用說這些年烏克蘭發生的事。對很多立陶宛人來說,俄羅斯象徵的是壓力,是失去主權的記憶。」

雷娜塔低聲補了一句:「但這很矛盾吧?你從小用的語言、生活節奏……後來卻被提醒說,那是壓迫你的一部分。」

托馬斯再次點頭:「對,所以變成一種私密語言——有些人家裡還會用俄語,但在外面就不太講了,也不會主動提。」

茱莉亞望向窗外:「可道路、建築、整套制度……還是有一種蘇聯的影子。」

托馬斯喝完咖啡說:「國家可以脫離帝國,但要讓帝國從你心裡消失,要更久。」

A Writer on the Edge

Later in the afternoon, they walked up a gentle slope above the town. Pine trees framed the path, and the wind from the lagoon carried the scent of salt and resin.

At the top stood a modest house with a gabled roof and wide windows facing the water.

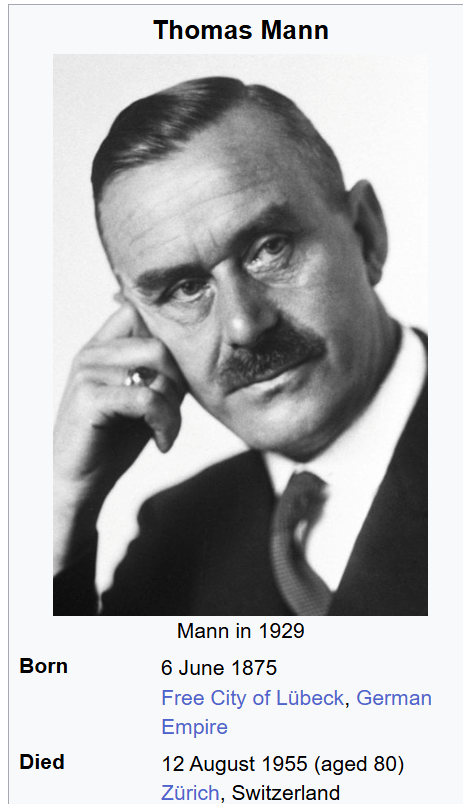

“Is this… Thomas Mann’s place?” Ben asked.

Tomas nodded. “He built it in the 1930s. He used to spend his summers here with his family.”

Emma added, “It was during his exile from Nazi Germany. He wasn’t yet stripped of citizenship, but he was already out of place — politically, culturally, morally.”

Renata stood near the fence, looking out at the lagoon. “Why here?”

Julia answered, “Because it was far, quiet, and still German-speaking at the time. But also… because it was a frontier. A place that wasn’t quite one thing or another.”

Tomas said, “He called it ‘my little house on the border of Europe’.”

Ben asked, “Did he write anything here?”

Emma nodded. “Yes. Joseph and His Brothers — parts of it. And essays about exile, identity, civilization. He loved the landscape, but I think the setting also mirrored his state of mind.”

Julia added, “That tension — between longing and departure — is everywhere in his work.”

They stood quietly for a moment. The lagoon shimmered below. The house behind them stood calm, not grand, but deliberate — like someone had chosen it, carefully.

邊境上的作家

下午時分,他們走上鎮邊一處緩坡。松林圍繞著小路,潟湖的風帶著樹脂與鹹味。坡頂是一棟小屋,屋頂斜斜的,窗戶朝向湖面敞開。

「這是……托馬斯·曼的故居?」班問。

托馬斯點頭:「他在 1930 年代蓋的,每年夏天會帶家人來這裡。」

艾瑪接著說:「那時他剛從納粹德國流亡,還沒有被正式取消國籍,但在政治、文化、甚至道德上,他已經是個局外人。」

雷娜塔靠著木欄望向潟湖:「那為什麼會選這裡?」

茱莉亞說:「因為這裡夠遠、夠安靜,而且當時還是講德語的地方。但我想,更重要的是——這是一種邊境感,一個不完全屬於哪一邊的地方。」

托馬斯補充:「他曾稱這裡是『我在歐洲邊緣的小屋』。」

班問:「他在這裡寫東西嗎?」

艾瑪點頭:「有,《約瑟與他的兄弟們》部分章節就是在這裡完成的。他還寫了不少關於流亡、身份與文明的散文。他喜歡這片風景,但我想這地點也反映了他的心境。」

茱莉亞說:「那種離開與懷念交錯的張力,在他所有作品裡都感覺得到。」

他們安靜地站了一會兒。潟湖在下方微微閃光,小屋靜靜地立在坡上,不大、不華麗,但有種被深思熟慮後選中的感覺。

Ben looked at the house. “I’ve heard of Thomas Mann, but I don’t know much. Who was he exactly?”

Emma answered, “One of Germany’s greatest writers. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929 — wrote Buddenbrooks, The Magic Mountain, Death in Venice.”

Julia added, “And he was very vocal against the Nazis. Left Germany early and spent most of the war years in exile.”

Tomas nodded. “He stayed here for just a few summers, but this place was important. Quiet. Far from politics. He wrote, walked, thought.”

Ben looked toward the lagoon. “Makes sense. It feels like the kind of place where ideas settle.”

班望著那棟小屋說:「我聽過托馬斯·曼,但不是很熟。他到底是誰?」

艾瑪說:「是德國二十世紀最重要的作家之一,1929 年拿過諾貝爾文學獎。寫過《布登勃洛克一家》、《魔山》、《威尼斯之死》。」

茱莉亞補充:「他早期就反對納粹,後來流亡海外,幾乎整個二戰期間都不在德國。」

托馬斯點點頭:「他在這裡只住了幾個夏天,但對他很重要——安靜、遠離政治。他在這裡寫作、散步、思考。」

班看向潟湖:「的確有那種讓人靜下來的地方感覺。」

Lunch

They picked a small restaurant near the harbor — white wooden walls, red shutters, a carved sign that read Küstenhaus. The subtitle said: East Prussian Cuisine.

Inside, it smelled like sauerkraut and smoked pork. They found a table by the window.

Renata scanned the menu. “Pork knuckle, bratwurst, potato salad. Not what I expected this far from Germany.”

Tomas chuckled. “A lot of these recipes go back to East Prussia. Some people here still cook them at home.”

Emma added, “The food stayed longer than the language.”

Julia said, “And the buildings too. But politically, the past is more complicated.”

Ben looked out the window. “This area touches Russia, right?”

Tomas nodded. “Yeah. The border’s just a few kilometers south of here. Used to be all one province.”

Emma said, “Now it’s split between NATO and Russia. Not exactly a comfortable setup.”

Renata asked, “Do people here worry about that?”

Tomas paused. “Some do. Especially after Ukraine. Everyone remembers what it felt like to be ‘watched.’”

Julia stirred her tea. “It’s a beautiful place, but it doesn’t feel stable.”

Tomas nodded. “It isn’t, really. These dunes used to move constantly until they were stabilized in the 19th century.”

Emma asked, “Is climate change making that harder?”

“Yes,” Tomas said. “The storms are stronger, rainfall patterns are shifting, and winters are warmer. All that affects the sand movement and vegetation.”

Ben asked, “Is the area shrinking?”

“Not shrinking, exactly,” Tomas replied. “But the balance is changing. Some dunes are eroding faster. Others are shifting. And the forest line keeps creeping.”

Renata looked out the window. “Has it gotten hotter?”

“Definitely. Spring comes earlier. Insects show up weeks ahead. And we don’t get proper snow anymore — just wet months.”

午餐

他們在港邊找到一家小餐館,白牆、紅色百葉窗,門口掛著一塊牌子寫著 Küstenhaus,下面註明:「東普魯士料理」。

一進門就聞到酸菜和燻肉的味道。他們選了靠窗的位子。

雷娜塔翻著菜單說:「燉豬腳、香腸、馬鈴薯沙拉——這離德國可不近,還是吃得到這些?」

托馬斯笑了一下:「這些做法從東普魯士就留下來了,這裡一些家庭自己還會煮。」

艾瑪補充:「菜留得比語言還久。」

茱莉亞說:「建築也留著。不過政治就麻煩多了。」

班看著窗外問:「這裡離俄羅斯很近對吧?」

托馬斯點頭:「對啊,再往南幾公里就是邊界。以前全都是同一個省。」

艾瑪說:「現在變成北約和俄國的接縫處,誰都不會覺得輕鬆。」

雷娜塔問:「那這裡的人會擔心嗎?」

托馬斯想了幾秒才說:「有人會,尤其烏克蘭那邊開戰以後。大家都記得以前那種被盯著的感覺。」

茱莉亞攪著茶說:「這地方雖然美,但總覺得不太穩定。」

托馬斯點頭:「實際上也不太穩定。這些沙丘以前會一直移動,後來是十九世紀才開始用人工方式固定住。」

艾瑪問:「那現在地球暖化會不會讓控制變難?」

托馬斯說:「會啊。現在風暴強度變高、降雨變得不規律、冬天也不太冷了——這些都會影響沙子的移動和植被的生長。」

班問:「沙丘會不會面積變小?」

托馬斯搖搖頭:「不是整體變小,而是平衡在變。有些沙丘侵蝕得比較快,有些開始位移。森林也一直往沙地推進。」

雷娜塔看著窗外問:「那氣溫有明顯變嗎?」

托馬斯說:「有啊,春天來得早,昆蟲比以前早好幾週出現,冬天也很少真的下雪,變成又濕又暖的幾個月。」

Chocolate, With a Surprise Twist

The waitress returned with dessert — apple strudel and a dense slice of dark chocolate cake.

Renata took a bite and raised her eyebrows. “This is really good. Rich, not too sweet.”

Emma nodded. “Honestly, I didn’t expect chocolate like this in Lithuania.”

Julia said, “It’s not just local. I read that Lithuania exports a surprising amount of chocolate — not only to Europe, but even to parts of Asia.”

Ben looked up. “Wait, seriously? Asia?”

Tomas nodded. “Yes. Especially to places like Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. Not the luxury brands, but good quality and affordable. Some people actually prefer the plainer flavors.”

Emma said, “That makes sense. It’s solid chocolate, not overloaded with sugar or additives.”

Renata smiled. “And if you put it next to one of those fancier boxes, I’d probably still pick this.”

Tomas added, “Some of the factories here date back to Soviet times, but they’ve modernized fast. A few even sell under new names just for export.”

巧克力,也走得挺遠的

服務生送上了甜點——蘋果捲和一片厚實的黑巧克力蛋糕。

雷娜塔咬了一口,抬起眉毛說:「這個好吃耶,味道濃但不會太甜。」

艾瑪點頭:「老實說,我沒想到立陶宛的巧克力會這麼有水準。」

茱莉亞說:「這不只是本地在賣喔。我看過報導,立陶宛的巧克力外銷量很高,不只賣到歐洲,還有出口到亞洲。」

班抬起頭:「真的假的?亞洲也買?」

托馬斯點頭:「有啊,像日本、台灣、韓國這些地方。雖然不是精品巧克力,但品質好、價格也親切。有些人甚至比較喜歡這種比較原味的口感。」

艾瑪說:「真的,它的味道很實在,不會加一堆有的沒的。」

雷娜塔笑著說:「如果放在高級禮盒旁邊,我搞不好還是會選這個。」

托馬斯補充:「有些巧克力工廠是蘇聯時代留下來的,但這幾年改得很快,還有些會用不同品牌名稱專門出口。」

發表留言