The Climb After Lunch

After lunch, they sat in stillness for a moment.

The plates were empty but warm, sunlight touched the edge of the table, and the taste of dill butter lingered in the mouth. Outside, the street was quiet—just the rustle of leaves.

“Shall we walk a bit?” Tomas asked. “There’s something I’d like to show you.”

They left the restaurant and followed a gently rising street.

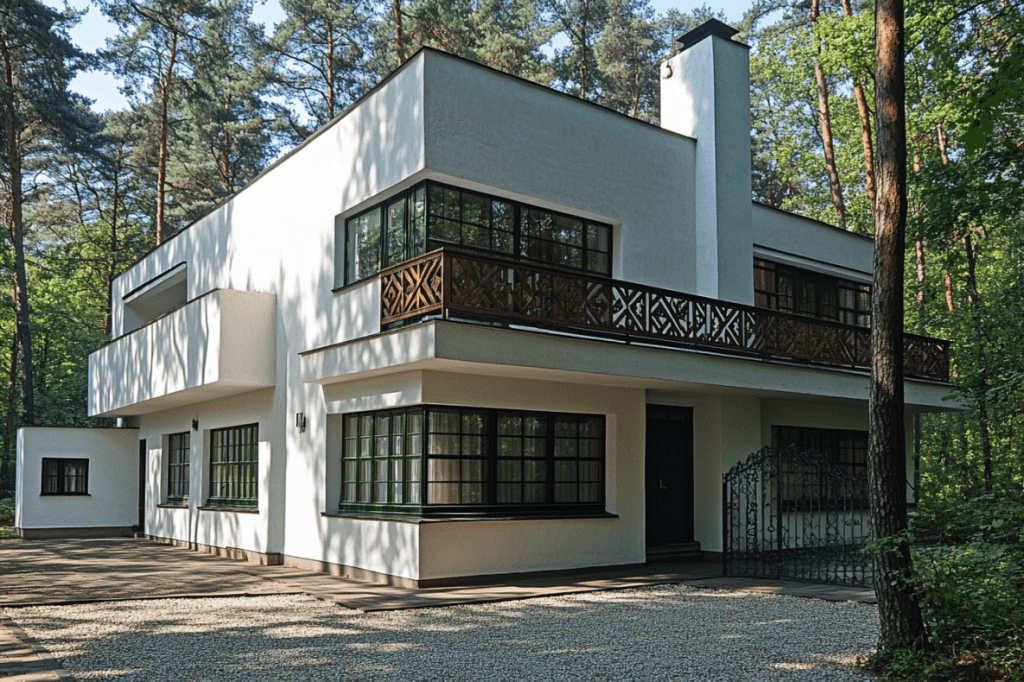

The city, so flat just moments ago, began to shift. A quiet incline opened ahead, lined with interwar houses—each with a private yard, a tall fence, and a certain reserve in its design.

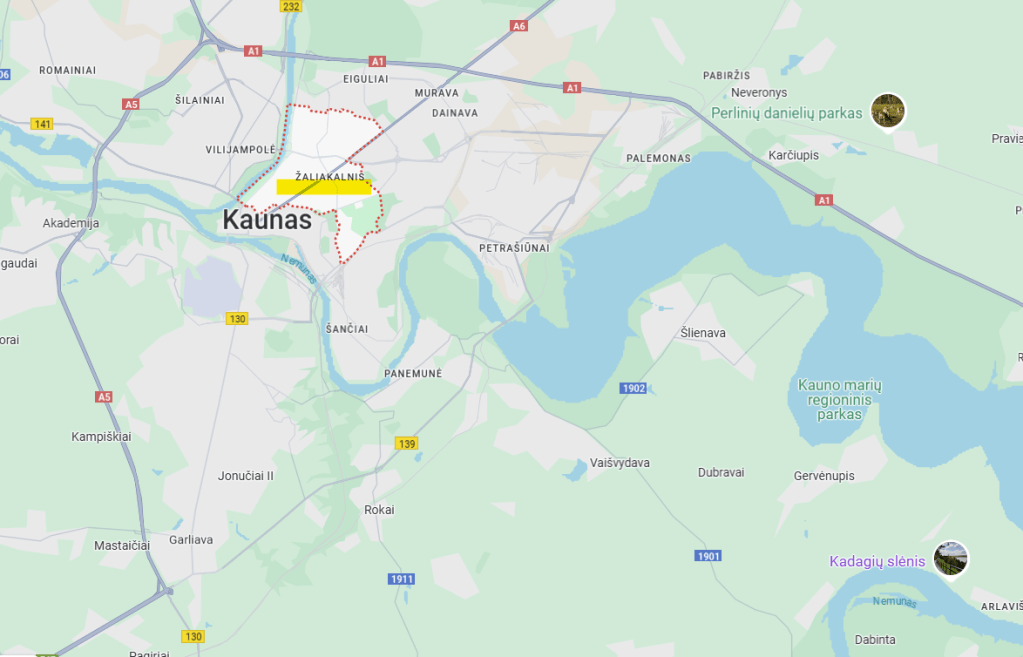

“This is Žaliakalnis,” Tomas explained.

“It was built for officials, professors, architects… Those who imagined that to live higher up meant to be part of something higher.”

“So not all of Kaunas is like this?” Emma asked, looking up at a sun-drenched balcony.

“No,” said Tomas. “Where we had lunch, that’s still the horizontal core of the city. But this area—this was planned as a vertical symbol.”

Ben paused before the funicular. “Was this built during the Soviet period?”

“No,” Tomas smiled. “1931. It was a statement of modern Lithuania.”

They entered the car—wooden benches, brass handles—and began to ascend. Outside, rooftops and antennas slipped away beneath them.

“Does Vilnius have a place like this?” Julia asked, resting against the window.

Tomas shook his head. “It has hills, yes. But they carry a different meaning—those are hills of memory. The Castle Hill, the Hill of Three Crosses…”

Emma nodded. “There, to climb is to return to the past. Here, it was once a way forward.”

“And then,” Ben said softly, “that future was overwritten. One utopia after another.”

The funicular eased into the upper station.

They stepped out onto a small platform above the city. Below: bridges, spires, rooftops folding into the horizon.

No one spoke. Only the sound of leaves above them—and the slow, unspoken breath of a city remembering itself.

午後登高

吃飽之後,大家靜靜地坐了一會兒。

空盤子留著熱氣,窗邊陽光灑在桌角,蒔蘿奶油融化的味道仍留在嘴角。外頭的街道安靜,只有樹葉微微晃動的聲音。

「要不要走一走?」Tomas 抬頭問,「我想帶你們去一個地方。」

他們離開餐館,走上緩緩上行的街道。

原本平坦的城市逐漸開始有了斜度,轉角後,是一座安靜的坡道,街道兩旁是戰間期留下的住宅,一戶戶都有自己獨立的小庭院與高牆。

「這一區叫 Žaliakalnis,」Tomas 說,「從前是知識分子與官員的住宅區。他們希望『向上居住』,不只是字面上的上坡,也是社會象徵。」

「所以不是整個考納斯都這樣?」Emma 一邊走一邊看著街邊的陽台。

「不是,」Tomas 回應,「你們午餐所在的地方還是屬於城市的平面核心。只有這一區,有計劃地朝高地發展。」

Ben站在纜車站入口前,抬頭看了看軌道。「這是蘇聯建的?」

「不是,」Tomas 微笑,「1931年就通車了,是現代化象徵的一部分。」

他們走進纜車車廂,木製座椅、黃銅拉環,緩緩啟動。

窗外的屋瓦、花園與天線一一向後滑去。

「維爾紐斯也有像這樣的上坡區域嗎?」Julia 靠著車窗問。

Tomas搖搖頭:「有高地,但性質不同。那裡的山,是歷史與宗教記憶的載體,例如城堡山、三十字架山。」

Emma補充:「的確,在維爾紐斯,走上山更像是回到過去。這裡的上坡,卻是走向一個曾被相信的未來。」

「但那個未來,後來被別的意識形態接手了,」Ben低聲說,「一個烏托邦接著另一個。」

車廂靜靜滑入山上的車站。

他們下車,站在一座平台上,俯瞰整座城市——河流、橋樑、教堂圓頂,一層層交疊的屋頂靜靜伸展向地平線。

沒有誰說話。只有風聲穿過樹梢,以及城市不動聲色地呼吸。

What the Slope Reveals

They walked to the edge of the platform, where a low stone wall opened to the view below.

From here, Kaunas unfolded like a living map—the river curled through the city center, the red roofs of the old town pressed tightly together, and in the distance, bridges and neat rows of postwar apartment blocks stretched toward the horizon.

The sunlight fell at an angle, casting everything into a still, warm hush.

Ben watched in silence for a moment, then said, “I always thought the Soviets were all about equality. But standing here… the landscape tells a different story.”

Tomas nodded. “Slogans can be rewritten quickly. Geography takes its time. Žaliakalnis is like the city’s subconscious—no matter who’s in power, they end up using it to draw lines.”

“Because space speaks,” Emma added. “Not just buildings, but where they’re placed, what they overlook, what they hide. Meaning piles up.”

Julia didn’t respond immediately. She pointed to a cluster of buildings below. “That part must be from the socialist period. Boxy, uniform, aligned.”

Tomas smiled. “Yes. That was their attempt to flatten space. But no one noticed they were still building them downhill.”

Ben looked up at the quiet houses beside them—interwar homes with balconies and gardens, perched calmly along the slope.

He spoke softly, almost to himself, “That’s the thing about utopias. They’re always built on someone else’s elevation.”

A breeze stirred the leaves overhead. They stood there a little longer, saying nothing more, letting the lines of the city settle into their thoughts.

坡地所揭示的事實

他們走到平台邊緣,站在一處沒有欄杆的石牆前。

從這裡望下去,考納斯像是一張攤開的地圖——河流彎曲地穿過城區,老城的紅屋頂密集地擠在一起,遠處還能看到鋼鐵橋梁與一排排規整的新住宅樓。

陽光斜照下來,城市彷彿靜止在午後的光影裡。

Ben 靜靜地看了一會兒,忽然開口:「我還以為蘇聯是人人平等的社會。但站在這裡……這層次分明的地勢,實在太誠實了。」

Tomas點點頭,語氣低沉:「紙上的口號改變得很快,但地形不會。Žaliakalnis 就像城市的潛意識——不管誰來掌權,都會不自覺地用它來分層。」

「那是因為空間會說話,」Emma 接著說,「不只是建築,而是它們在什麼位置,從哪裡望下來,又遮住了什麼。這些都會累積意義。」

Julia 沒有說話,只是往下望了一眼,指著一棟樓說:「那區應該是社會主義時期的集合住宅吧?方方正正、排列整齊。」

Tomas 笑了笑:「是啊,那是 Soviets 嘗試『打平空間』的時候蓋的。但很少有人注意到,那些房子還是在低處蓋的。」

Ben收回目光,看著高處旁邊的一排老屋,那些建於戰間期、帶著陽台與院子的住宅靜靜坐落在山坡邊。

他像是自言自語:「烏托邦的故事啊……總是一層接著一層,蓋在別人的高度之上。」

風輕輕地吹過來,樹葉沙沙作響。他們就站在那裡,沒有再說話,只讓城市的輪廓和光線,慢慢地在心中沉澱。

Ben stood quietly on the platform, watching the little red-and-white funicular car slide back down the slope.

From up here, it looked like a toy slipping into the folds of the city. He turned slightly toward Tomas, his voice half-curious, half amused.

“This tiny thing… You’re telling me it was really a transport system? How many people could it carry in a day?”

Tomas smiled. “Not many. A dozen or so at a time. But they didn’t build it for traffic relief.”

“Then what for?” Julia asked.

“It was a gesture,” Tomas said, pointing to the boundary between the slope and the city below.

“A modern gesture. They wanted this temporary capital to feel like a real European city—vertical layers, technical ambition, order, and a sense of future.”

Emma added, “Like drawing a line. A line that selectively allows access. The funicular didn’t just move people up the hill—it offered a path upward, but not for everyone.”

Ben nodded slowly, eyes settling on the row of interwar houses beside them. “So it wasn’t built for efficiency. It was built for symbolism.”

“Exactly,” said Tomas. “This car didn’t just carry people. It carried an idea.”

The breeze moved softly through the trees. Below them, the city lay still, like a map waiting to be read—and the tracks of the funicular traced a deliberate diagonal line across it.

Ben 靜靜地站在平台上,看著剛才搭乘上來的纜車滑回山腳,紅白色的小車廂像玩具一樣縮進城市的褶皺裡。

他偏頭看了 Tomas 一眼,語氣帶著半是懷疑半是玩笑的口吻。

「這麼小的纜車……你說它真的是交通工具嗎?每天能載多少人?」

Tomas 笑了笑:「的確不多。每次大概十幾人。但當初他們建這個,可不是為了解決什麼通勤壅塞問題。」

「那是為什麼?」Julia 問。

「這是個姿態,」Tomas 指著坡道與城市之間的界線。

「一種現代化的姿態。他們要讓這座臨時首都看起來像歐洲的一線城市,有垂直的構造、有技術、有秩序、有未來。」

Emma 接著說:「就像畫出一條線——一條能選擇性的通行線。它不只是方便上下山,而是為特定階層開闢了一種『上升的路徑』。」

Ben點點頭,目光落在山坡邊的那些戰間期住宅。「所以不是為了效率,而是為了象徵。」

「對,」Tomas 說,「這纜車承載的不只是人,更是他們對現代、對國家的想像。」

風輕輕掠過樹梢,城市下方靜靜地展開,像是一個等待解讀的地圖,而那條纜車軌道,正好是其中一筆刻意劃下的斜線。

They turned a corner past an old chestnut tree and entered a narrower lane. The houses here were more modest—two-story dwellings, dark stucco walls, some with geraniums in the window boxes.

Just then, Tomas slowed his steps and raised a hand.

“Antanas!”

A man in a grey-blue cardigan was tending to his garden bed near the entrance. He looked up with a puzzled frown, then brightened as recognition set in.

“Tomas! I don’t believe it.”

They shook hands warmly.

“I’m walking with some friends,” Tomas said. “They just came up from the funicular—wanted to see this part of town.”

“Perfect timing,” Antanas smiled. “This house was built by my grandfather, back in the interwar years. He was a lecturer at the medical faculty. The government back then encouraged professors to settle here—build a real academic neighborhood. Now… students hardly know that part of history.”

Emma and Julia stepped closer. Ben lingered near the door, eyeing a metal plaque that read: Residence of a Kaunas University Professor, 1936–1944.

“Do you still teach?” Julia asked.

Antanas nodded. “At Kaunas University of Technology. Social theory. For me, this neighborhood isn’t just home—it’s a living backdrop to every class I teach. If you have time, I’d be happy to show you the yard. The old laundry shed is still there, and the original wooden staircase.”

Tomas looked at the others, a faint smile playing on his lips. “Shall we? His tea is usually worth the detour.”

他們繞過一棵老栗樹,轉進一條更窄的小巷。這一帶的房子更加低調,多是二層樓的舊宅,牆面深色,有些窗邊種著天竺葵。

就在那時,Tomas忽然停下腳步,微笑著對前方揮了揮手。

「Antanas!」

一位穿著灰藍針織外套的男子正站在自家門前,用鋤頭翻著花圃的土。他聽到叫聲後轉過身,露出皺著眉頭的思索表情,但隨即眼神一亮。

「Tomas!這可真是稀客。」

Tomas 上前與他握手,語氣熟絡:「我帶幾位朋友來散步。他們剛從 Žaliakalnis 纜車上來,想看看這一區的老房子。」

「剛好,」Antanas 笑了,「你們來得真巧,這房子就是我祖父戰間期蓋的。他是醫學院的講師,當年政府鼓勵教授搬到這一區來,說要打造一個知識社群。現在——唉,學生們已經不知道這段歷史了。」

Emma 與 Julia不約而同走近一步。Ben則看著門邊一塊金屬牌,上面刻著「此處曾為 Kaunas 大學教授居所 1936–1944」。

「你現在還在教書嗎?」Julia 問。

Antanas 點點頭:「我在考納斯科技大學,教社會理論。這個街區對我來說不只是家,更像是我講課時的實景背景。你們若有空,我可以讓你們進來看看院子,還保留著當年的洗衣亭和老木樓梯。」

Tomas 看向其他人,嘴角浮現一絲笑意:「要進去坐一下嗎?他們家的茶水一向很不錯。」

發表留言