Turning North: A Morning Plan over Coffee

The hotel’s breakfast room sat quietly on the ground floor, with windows facing the street. Outside, the chestnut leaves stirred in the breeze as a few sparrows hopped along the sidewalk, pecking at scattered crumbs.

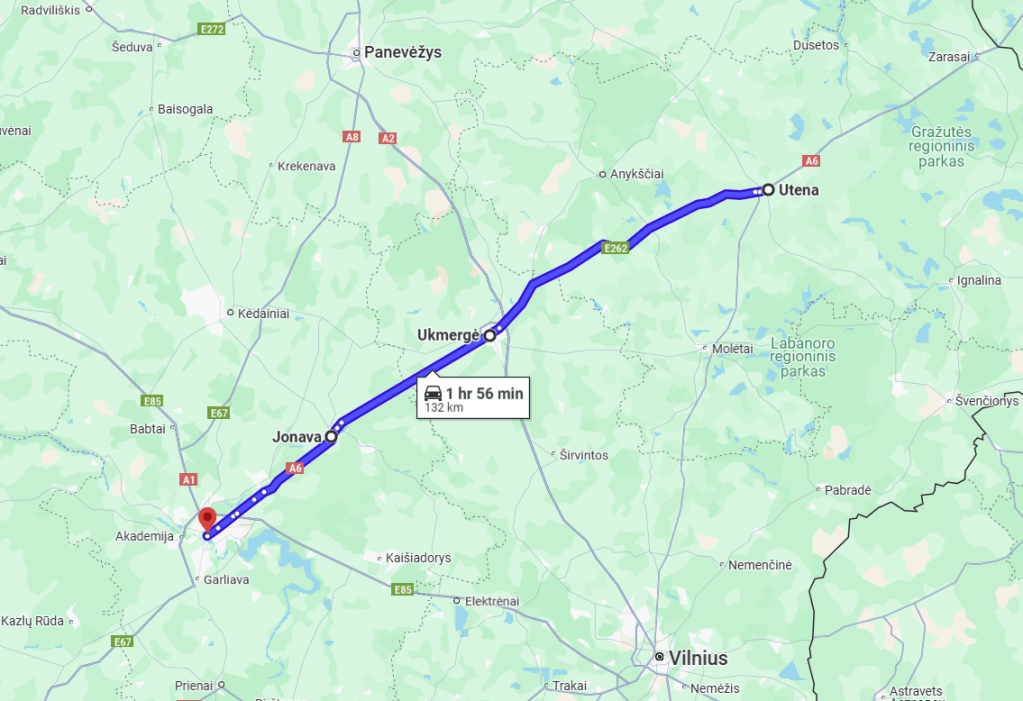

Tomas sliced into a piece of rye bread while opening the map on his phone. “Today we can take the northern route—through Jonava and Ukmergė, then onward to Utena.”

Ben lifted his coffee cup. “I looked up Ukmergė last night. It’s actually one of the oldest towns recorded in Lithuanian history—mentioned as early as the early 1300s. It used to be a noble estate, had a wooden castle, got burned down, rebuilt again…”

Tomas nodded. “It sat on the road between Vilnius and Riga, so in medieval times it was a pretty active trading post. Now it’s more of a pass-through place.”

Emma flipped through a small hotel brochure. “If we get there by noon, we could stop for lunch and take a short walk through the old streets before heading on.”

Julia agreed. “Sounds good to me. Less rushing, and it’s always interesting to feel the rhythm of a real town—not just tourist spots.”

Renata added, smiling, “Didn’t you want to film street scenes? I bet the rooftops and old lamps in Ukmergė will be great. I heard the old post office still has its original brickwork.”

They kept talking and adjusting the map as sunlight spilled across the breakfast table, warming the plates and making the morning feel like a fresh beginning.

向北出發的旅程規劃

旅館的早餐室位在一樓,一面靠著街道的窗子。窗外的栗樹葉子在晨風中輕晃,幾隻麻雀跳上跳下,啄著人行道邊的麵包屑。

Tomas 一邊切著黑麥麵包,一邊打開手機地圖:「我們今天可以走北邊那條線,經過 Jonava 和 Ukmergė,接著一路往 Utena。」

Ben端起咖啡,說:「Ukmergė 這地方我稍微查了一下,是立陶宛最早有書面記載的城市之一,早在十四世紀初就出現在文獻裡。曾經是貴族領地,也有過城堡遺址,後來被火燒毀又重建。」

「對,」Tomas點點頭,「它的位置剛好在維爾紐斯和里加之間,所以在中世紀是一個重要的轉運點。但現在很多人只是開車經過。」

Emma翻著旅館提供的小摺頁:「如果我們到的時間差不多是中午,搞不好可以在那邊吃午餐,繞一圈老街再上路。」

Julia說:「這樣安排挺好,不用太趕,也能感覺一下真正生活過的小鎮,而不是那種觀光化的地方。」

Renata笑了:「你們不是說要拍街景影片嗎?我想 Ukmergė 的屋頂和舊街燈會很好看。老郵局的磚牆據說也保留得不錯。」

他們邊吃邊把地圖拉大縮小,訂下今天的大致方向。陽光從窗戶照進來,把每個人眼前的盤子都染上了一層明亮的橘色。

From Kaunas to Ukmergė

They packed their bags and loaded the car. The morning sun was still gentle, and the streets were only beginning to stir. As they pulled away from the hotel, Emma glanced back at the white façade—its linen curtains still swaying softly at the window.

“I like this feeling,” she said, “leaving the city slowly.”

Once they turned onto the road heading north, the scenery began to change. The outskirts gave way to open fields.

The rapeseed had already bloomed, but faint traces of yellow still clung to the edges. Ben snapped a few shots through the window, catching reflections of sunlight across the glass.

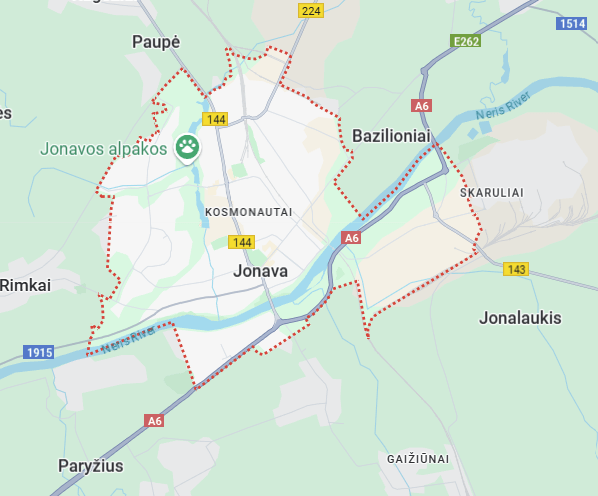

The first town they passed was Jonava. They didn’t stop—just looped gently along its edge.

“This place used to be heavy in industry,” Tomas said. “Chemical plants, river transport. It was a busy town along the Neris.”

Julia looked out at the row of flat-roofed buildings. “Feels like a stage that’s gone quiet. Like something used to happen here all the time.”

As the car rolled past the outskirts of Jonava, Ben looked out at the long row of industrial buildings. “Why here?” he asked. “Is it just because of transportation?”

Tomas nodded. “Partly. It’s right on the Neris River, which used to be a transport route for both raw materials and finished goods. Later, it was connected by rail too.”

Emma added, “And during the Soviet era, a lot of industry placement wasn’t purely market-driven. They considered geographic balance, labor distribution, even strategic factors.”

Ben thought for a moment. “So was there some kind of local resource here?”

“Not really,” Tomas said. “But the nearby rural areas provided a steady labor force. And chemical production—well, it’s too risky to put inside a major city, but too costly to isolate completely. So mid-sized cities like Jonava made sense.”

Julia glanced into the rearview mirror. “Were those factories supplying the entire Soviet Union?”

“Yes,” Tomas said. “The fertilizer plant here was one of the major suppliers. A lot of the output went by rail to Russia, Belarus—even as far as Central Asia.”

Chemical factory during the Soviet era

Beyond Jonava, the road stretched straighter, the landscape broader. Scattered houses appeared along the way—red brick walls with slanted chimneys, curtains fluttering faintly behind worn windows.

Tomas rolled the window down. The breeze carried hints of grass, sun-warmed soil, and the faintest trace of dust.

As they approached Ukmergė, the view narrowed again. Low apartment blocks gave way to older redbrick buildings and timber homes.

The town center wasn’t tall, but the proportions were just right—quiet, balanced. Some shop signs still curved in wrought iron, and old glass display windows rippled slightly under the light.

“This has more character than I expected,” Renata said.

They parked beneath a large linden tree, planning to get lunch before exploring. Sunlight filtered through the branches and danced on the cobblestones, as if the whole town was still breathing slowly, patiently.

從考納斯前往烏克梅爾蓋

他們收拾好行李,把背包放進車廂,早上的陽光還不算刺眼,街道上只有三三兩兩的車輛。離開旅館時,Emma回頭看了一眼那棟白牆旅館,窗台的窗簾還微微飄動。

「我喜歡這種從城市慢慢退場的感覺,」她說。

車子轉出街口,進入通往北方的國道。經過郊區時,視野漸漸開闊。田地開始出現,油菜花田已經開完,但田埂上還殘留著一絲淡黃。Ben隔著車窗拍了幾張照片,陽光灑在玻璃上閃出細碎的反光。

第一個比較大的城鎮是 Jonava。他們沒有停車,只在城邊緩慢地繞了一圈。

「這裡工業區不少,」Tomas說,「以前是化工業重鎮,也因為靠著 Neris 河而發展起來。」

Julia看著路邊一整排平屋頂的工廠建築,說:「感覺這裡曾經很忙,現在安靜得有點像退場的舞台。」

車子緩緩駛過 Jonava 的外圍,Ben看著那一整排工廠建築,問道:「為什麼會是這裡?化工廠設在這種地方,是因為交通嗎?」

Tomas點頭:「部分是這樣。這裡靠著 Neris 河,過去用來運輸原料和成品很方便,後來又有鐵路接通。」

Emma補充:「而且蘇聯時期,很多產業的布局其實不完全是市場導向的。他們會考慮地理平衡、人力分配、還有戰略因素。」

Ben想了一下:「那這裡會不會是因為有某種原料?」

Tomas說:「不特別有天然資源,但附近農村提供穩定勞力。然後化工這種東西——其實你放在城市太危險,放太遠又運輸不便,所以像 Jonava 這種中型城市剛好。」

Julia抬頭看了一眼後照鏡:「那時候生產的東西,是供應整個蘇聯的嗎?」

「對,」Tomas說,「這邊的化肥廠是全蘇聯重要供應者之一。很多產品會經由鐵路送到俄羅斯、白俄羅斯,甚至中亞。」

蘇聯時期 Jonava 化工廠

離開 Jonava 後,道路變得更筆直,也更空曠。偶爾會看到一兩棟獨棟的老房子,紅磚牆邊有斜斜的煙囪,有些窗台還掛著舊窗簾。

Tomas打開窗戶,風吹進來時帶著草的味道和一點塵土。

快到 Ukmergė 時,風景慢慢收攏起來。

郊區先出現一排排低矮的公寓樓,之後是更舊的紅磚屋與木造建築。市中心不高,但街道兩側的比例恰到好處,有些店鋪還保有老式鐵牌與彎曲玻璃櫥窗。

「這裡比我想像得還有味道,」Renata說。

他們在一棵大椴樹下停了車,打算先找地方吃午餐。陽光穿過樹葉,在石板街道上灑下一片晃動的光影,彷彿整個小鎮還在緩慢呼吸著。

Lunch

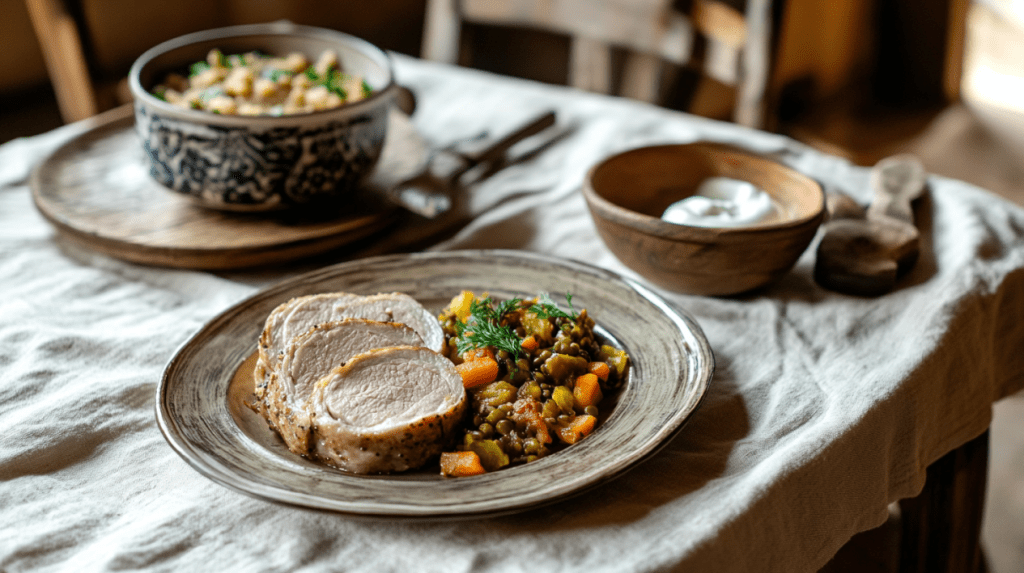

They sat down in a small red-brick restaurant.

There were only a few other diners—locals, by the look of them.

Old black-and-white photos hung on the walls, and the smell of something slowly simmering drifted in from behind the counter.

The menu was short but solid. Tomas suggested the pork roulade with buckwheat, a side of stewed vegetables, and a house-made cultured cream.

“Food around here is simpler than in the coastal regions,” he explained. “More about land produce—pork and buckwheat take center stage.”

Ben nodded. “Yeah, dishes like this don’t try to impress. But they tell you where you are.”

Julia cut into her buckwheat cake. “I’ve noticed central Lithuanian flavors are pretty steady—not spicy, not too salty, but rich in their own way.”

Emma added with a smile, “And they go the distance. Unlike trendy dishes that wear you out halfway.”

Renata looked down at her slice of dark rye bread. “This food feels like it came out of the place itself. Not made to be looked at—just… lived with.”

Outside, the sound of a bicycle passed by. A breeze stirred the linden leaves along the street. They kept eating quietly, not in a hurry to leave.

午餐

他們在一間紅磚外牆的小餐館坐下,餐廳裡只有幾桌人,看起來像是當地居民。牆上掛著老照片,櫃檯後傳來廚房慢火燉煮的味道。

菜單不長,但實在。

Tomas建議點豬肉捲配蕎麥、燉菜、還有自家做的奶油發酵乳酪。

「這一帶的飲食風格比靠海的地區還要樸實一點,」他說,「比較偏重農產品,豬肉和蕎麥是主角。」

Ben點頭:「確實,這種地方的料理沒有太多裝飾,但很有地方感。」

Julia切了一塊蕎麥餅:「我發現中部地區的口味比較穩定,不太辣、不太鹹,但很有深度。」

Emma笑說:「也很耐吃,不像有些新潮料理吃到一半會覺得累。」

Renata看著自己的黑麥麵包說:「這種地方的飲食,感覺跟這座城市一樣,是『活過來』的,不是用來吸引人的,而是自己長出來的。」

窗外傳來腳踏車經過的聲音,一陣風捲起了路邊椴樹的葉子。他們在桌邊安靜地吃著,不急著離開。

Brick Walls and Quiet Stories

After lunch, they walked slowly down the street.

The afternoon sun in Ukmergė cast a golden hue across the quiet sidewalks. A few elderly locals sat on benches near the square.

As they passed a building with deep red walls and weathered wooden frames, Julia remarked, “There’s a lot of brick here. More than what we saw in the western towns, I think.”

Tomas nodded. “This region has clay-rich soil. Since the 19th century, small local kilns produced bricks, so it was the most practical choice—cheap, local, and durable.”

Ben ran his fingers along the faded mortar lines. “Is that German brick style? You know, Backsteinbau?”

“Exactly,” Tomas said. “It started in Germany, then spread into the Baltic. In towns like Ukmergė, it evolved into a regional version—especially for public buildings.”

Emma added, “Post offices, warehouses, schools… those were built to show structure and function. It’s part of that early 20th-century functionalism—honest materials, no frills.”

Julia looked up at the surface of the wall. “And the aging makes it better, really. Brick absorbs time. Stucco peels—brick settles.”

Tomas smiled. “Exactly. Around here, brick isn’t just a material. It’s what stays.”

A red-brick building caught their attention. Its facade was a deep, soft red; the windows were framed in aged wood, the glass slightly warped. An old iron sign above the entrance read Cultural Center.

“Can we take a look inside?” Julia asked.

“This used to be the post office,” Tomas said. “After the war, they turned it into a local culture center. I think there’s a photo exhibit inside—some old objects too.”

They pushed open the wooden door. Inside, it was cool and quiet, with a faint smell of old paper and timber. Posters announced small exhibits, and a row of black-and-white photos lined one wall, showing scenes from Ukmergė’s past.

Ben stood before one photograph for a long while. It showed a 1930s street market, with their lunch spot visible in the background.

“That place used to be a general store,” he pointed out. “There’s something compelling about that kind of continuity.”

Emma nodded. “And the brick’s still there. It’s not just architecture—it’s the surface of memory.”

紅磚牆與故事

吃完午餐後,他們沿著街道慢慢走著。

Ukmergė 的午後陽光偏黃,街道上的人不多,只有幾個老人坐在廣場邊長椅上。

他們走過一棟牆面深紅、窗框斑駁的建築時,Julia輕聲說:「這邊的紅磚建築真的很多,感覺比西邊更密集一點。」

Tomas點點頭:「因為這一帶土壤含黏土,從十九世紀起就有很多小型磚窯,建材就地生產,紅磚成了最實際的選擇。」

Ben看著窗邊退色的磚牆紋理:「那種日耳曼式的磚砌風格是不是也有影響?」

「有,」Tomas說,「原本是從德國那邊來的 Backsteinbau,傳到波羅的海後慢慢變成本地的版本。在像 Ukmergė 這種小鎮,公共建築常見這種風格。」

Emma補充:「尤其像郵局、倉庫、學校這種,強調材料本身,不再遮掩結構,算是一種功能主義的體現吧。」

Julia邊走邊看:「而且這種磚牆老了之後,會變得更有紋理感,不像水泥剝落得那麼快。」

「嗯,紅磚老了還是穩,」Tomas笑說,「在這種地方,它不只是一種材料,更是一種留下來的感覺。」

不遠處,一棟紅磚建築吸引了大家的注意。牆面深紅而不刺眼,窗框是舊式的木框,玻璃有點波紋。門口掛著一塊舊鐵牌,寫著「文化中心」。

「我們可以進去看看嗎?」Julia問。

「這以前應該是郵局,」Tomas說,「戰後才改成文化館。我記得裡面有展一些地方的歷史照片和老物件。」

他們推開那扇木門,裡頭涼涼的,有淡淡的舊紙和木頭氣味。牆上貼著展覽資訊,還有幾張黑白照片展示過去 Ukmergė 的街道樣貌。

Ben站在一張照片前看了很久,那張拍的是一九三○年代的市集,背景正是他們剛吃午餐的那棟建築。

「那餐館那時候是雜貨店,」他指著畫面說,「這種連續性很迷人。」

Emma點頭:「而且紅磚都還在。那不是建築,是記憶的表面。」

From Brick to Pine: The Road into Aukštaitija

It was nearly 4:00 p.m. when they left Ukmergė.

Sunlight angled through the car windows and lit up the pages of the map book Julia was holding.

“We’re heading northeast now,” she said, flipping a page. “This is Aukštaitija—literally ‘the Highlands.’ It’s not mountainous, but the terrain is definitely more undulating than the west.”

“No wonder the road’s been rising and dipping more,” Emma said, looking out at the denser tree lines. “And you can start to smell the forest.”

“This is Lithuania’s oldest protected area,” Julia added.

“It was designated a national park during the Soviet era, but serious conservation began in the ’90s. There are over a hundred lakes here—most of them formed during the last glacial period.”

Ben raised his camera and snapped a shot of a clearing bathed in golden light. “This light’s incredible. Totally different from the weight of red-brick towns.”

“It’s quiet here too,” Renata said. “In towns, sound bounces off the walls. Here, it gets… absorbed.”

Tomas, eyes on the road, added, “We’ll be staying near Ladakalnis. Dinner’s at the guesthouse—small farm operation, good local food, apparently.”

Julia nodded. “Ladakalnis is one of the key viewpoints in this region.

The hill’s not very tall, but from the top you can see six lakes overlapping.”

Emma looked out at the sun slowly lowering behind the trees.

“It feels like the whole day’s been a transition. From history and bricks and memory… into something wilder.”

Ben took another shot and smiled. “A day that moved from walls to water.”

從紅磚到松林:走入奧克什泰提亞

他們離開 Ukmergė 時已經快四點,陽光沿著車窗斜照進來,照在 Julia 的地圖冊上。

她一邊翻頁一邊說:「我們現在往東北方向走,這一帶進入的是 Aukštaitija 地區——名字意思就是『高地地區』,雖然說不上是山,但地勢確實比西邊起伏。」

「難怪剛剛的公路開始有點上下坡了,」Emma說,看著窗外越來越密的樹林,「也開始有那種森林的味道。」

「這裡是立陶宛最早的自然保護區,」Julia補充,「從蘇聯時代就被劃為國家公園,但真正有組織地保護是在九○年代之後。這裡的湖泊超過一百個,大部分是冰河時期留下的。」

Ben拿起相機,隔著車窗拍了一張金色斜陽下的林間空地:「這光線真的太漂亮了。跟中部那種厚重的紅磚街景完全不一樣。」

「而且這裡真的很安靜,」Renata說,「不像城鎮有那種牆反射出來的聲音,這裡是『吸收』聲音的感覺。」

Tomas一邊開車一邊補充:「我們會先到靠近 Ladakalnis 的一間旅館,晚餐可以在那裡吃。他們有自己的小農場,東西應該不錯。」

Julia點點頭:「Ladakalnis 是這一帶的視覺高點之一。山丘不高,但可以看到六個湖交錯的樣子。」

Emma看著窗外逐漸低落的陽光說:「感覺這一天走得剛剛好。從歷史、紅磚、文化記憶,一路慢慢走進這種比較原始的空間。」

Ben又拍了一張照片,笑說:「也算是一天從牆轉向水的旅程。」

Arrival at the Edge of the Forest

Around 6:00 p.m., the car turned onto a narrow country road lined with tall pines.

The evening sun slanted through the branches, casting long golden streaks of light. After one final bend, the guesthouse came into view.

It was a two-story wooden building, painted a soft cream yellow, with a dark brown metal roof.

Perched slightly above a clearing, it faced a grassy slope that stretched gently toward the lake. A simple wooden sign hung by the door, showing the name of the place and check-in hours. The windows were half open, warm yellow light glowing from within.

They parked on the gravel drive, got out, and for a moment no one said anything. They just stood there, taking in the scene. From where they stood, they could see the lake shimmering with the color of the sky, its surface barely moving. No wind. Just the sound of birds.

Ben raised his camera near the car and took a shot. “This kind of light only happens where there are trees and cold water.”

Julia nodded. “Most of the lakes in this region are kettle lakes—deep bottoms, small surfaces. The temperature drops fast, and you get a real shift in air density.”

Emma opened the trunk. “The light here is nothing like the reflections we saw in town this morning.”

Tomas walked up to the door, checked the dinner schedule, and called back, “Dinner’s at 7:30. Let’s unload first. You’ve got time for a walk on the lawn if you want.”

Renata slipped off her jacket and draped it over her arm. “Feels like we didn’t just arrive—we crossed into a different rhythm.”

No one disagreed. Because she was right.

抵達森林邊界

傍晚六點左右,他們的車終於駛入一條兩側種滿松樹的鄉間小路。

陽光已經傾斜,從樹枝間落下一道道金色光線。經過最後一個轉彎後,旅館出現在眼前。

那是一棟兩層樓的木屋,牆面刷成奶油黃,屋頂是深棕色的金屬瓦。

建築坐落在一個小坡上,背後是一片森林,前方有一小塊草地延伸到湖邊。一個簡單的木牌掛在門邊,上面寫著旅館的名字與接待時間。窗戶半掩著,裡頭透出溫暖的黃光。

他們在碎石車道上停好車,下來後沒有人馬上說話,只是安靜地看著周圍的景色。

從這裡可以遠遠看到湖面反射著天色,水面微微晃動,沒有風聲,只有鳥鳴。

Ben站在車旁,舉起相機拍了一張:「這種光線只會出現在樹多、水冷的地方。」

Julia點頭:「這片區域的湖泊大多是壺穴湖,底部深但面積不大,水溫下降快,空氣會有明顯的密度感差異。」

Emma打開後車廂:「這裡的光線跟我們早上看到的城市反射完全不同。」

Tomas走向接待門口,確認了晚餐時間後回頭說:「七點半開飯。先把行李放好,大家有時間可以去前面草地走一圈。」

Renata脫下外套搭在手臂上,輕聲說:「我覺得我們不是來住宿,而是進入另一個節奏。」

沒有人反駁,因為她說得對。

發表留言